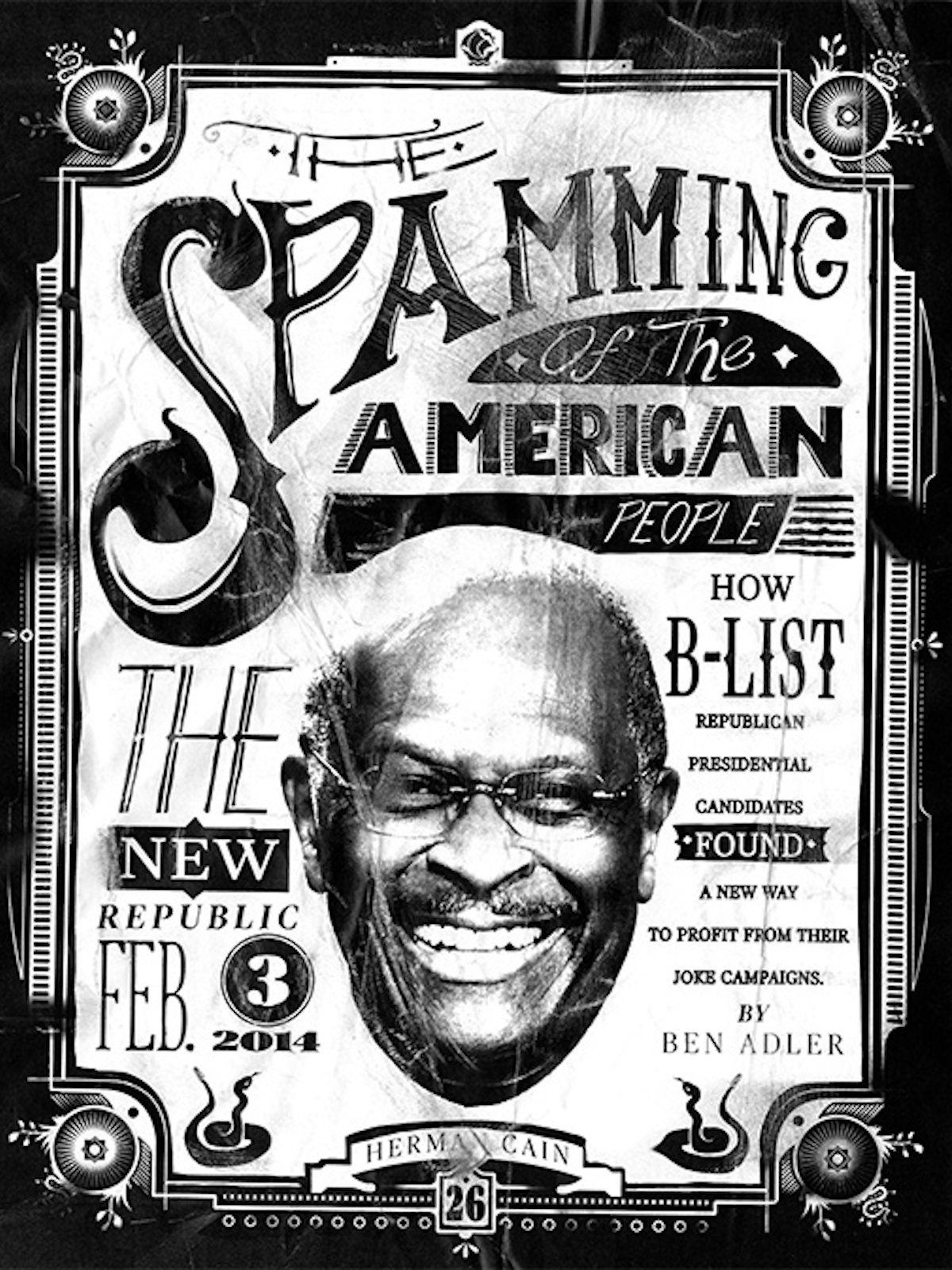

It has been more than two years since those giddy weeks when the political press brimmed with stories about Herman Cain, front-runner for the Republican nomination for president of the United States. But Cain die-hards can still stay abreast of the ex-candidate’s positions, via his e-mail list. Roughly 360,000 people receive the messages, which are sent through Best of Cain, the online media venture he set up after the campaign. The e-mails from Cain and the website’s small stable of writers arrive at a steady clip, many of them elucidating the Cain take on the news of the day. “A serious leader would have abandoned Obamacare long ago,” one proclaimed in December, clearing up any doubt about where Cain stood on the Affordable Care Act’s less-than-smooth rollout.

But sometimes Cain’s digital missives, like a conversation with a weird uncle, veer into the unexpected. An example—there are more and more to choose from—is a message that Cain sent to his followers last July bearing the subject line, “BREAKTHROUGH: REMEDY FOR ED!”

“ED” stood for, yes, erectile dysfunction. As for the all-caps-worthy remedy, its details were not immediately clear. Language in the body of the message identified the potion as a product of Natural Breakthroughs Research LLC; a link farther down led to a website urging men to submit their e-mail addresses in order to receive “a cool free report” on impotence abatement. Sitting through a lengthy video finally yielded more information on the wonder drug, TestoMax 200, a putative natural testosterone booster. The e-mail’s final offer varied by recipient—a common marketing tactic—but could be $69.95 for a month’s supply, or $47 for something called “The Potency Programme.” Not interested? Are you sure? “Women get lonely very easily,” began one version of the pop-up windows barring the exit. “Once you leave this page, your chances of getting your manhood mojo back will decrease dramatically.”

The erectile-dysfunction ad is one of more than 50 similar pitches for miracle cures and easy-money tricks that Cain has passed along to his e-mail followers over the past two years. While he has been particularly unabashed in his embrace of the practice, he is not the only past presidential candidate hawking sketchy products. Newt Gingrich now pings the e-mail subscribers to his Gingrich Productions with messages from an investment firm formed by a conspiracy theorist successfully sued for fraud by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Mike Huckabee uses his own production company’s list to blast out links to heart-disease fixes and can’t-miss annuities.

The joke about Cain and Gingrich during the 2012 campaign was that they weren’t at all serious about their pursuits of the presidency but instead just lining up future paydays. After Huckabee, who’d parlayed a strong showing in 2008 into publishing deals and his own Fox News show, declined to run again, some wags snickered that his new livelihood must have been too hard to give up. Now all three seem to be proving the cynics right. They’re not just cashing in on their candidacies the way some predecessors have, by translating increased visibility to higher speaking fees, more generous book advances, extra board appointments, and so on. Collectively, Cain, Gingrich, and Huckabee are pioneering a new, more direct method for post-campaign buckraking. All it requires is some digitally savvy accomplices—and a total immunity to shame.

Campaigns are very much in the lists business: lists of donors to call, lists of likely voters, lists of identified supporters, sub-lists of the addresses of the friendly voters needing rides to the polls. When the race is over, some of those databases become hot commodities as brokers peddle them to other candidates and like-minded interest groups willing to pay for access to their contents. A master file of the names and contact information collected during Alan Keyes’s perennial candidacies, for instance, remains “top performing,” according to direct-marketing clearinghouse NextMark, thanks to the highly engaged constituency it reaches: “These conservative individuals are passionately pro-life and pro-family and will do what it takes to ensure that their voices are heard!” The asking price is $100 per 1,000 names, with surcharges for pulling out targets by congressional district, gender, and other variables.

E-mail lists can be especially valuable, since the people on them have effectively asked to be contacted (not so with lists of phone numbers) and can be reached more reliably and more cheaply than they can through bulk snail-mailings. But there are specific rules governing how e-mail addresses are handled by office seekers. Generally, someone running for president enters the race with an existing list of e-mail followers—in Cain’s case, from the Atlanta talk-radio show he hosted and the syndicated column he wrote in the years leading up to the 2012 contest—which can be transferred to his or her campaign organization. That initial roster grows as supporters and fence sitters subscribe to the candidate’s bulletins. “Obviously, the size of the list expanded quite a bit,” says Best of Cain editor-in-chief Dan Calabrese. After Cain dropped out, he donated his enlarged list to Cain Connections, a newly formed super PAC, which then gave it to his new media company. Federal election statutes bar candidates from using campaign resources for personal use, but by passing the e-mail list through his PAC, Cain kept things inbounds. The maneuver, says Matt Sanderson, an election-law expert at the Washington, D.C., firm Caplin & Drysdale, was a means “to indirectly do what you otherwise couldn’t.”

Another route enterprising political figures can take is to keep their campaign and personal lists separate but use names from the former to bulk up the latter, and vice versa. This is the tactic pursued by Gingrich, who has sent sponsors’ e-mail ads from accounts maintained by both his production company and his old presidential campaign. Or, as Huckabee has done, a former candidate can wall off his campaign e-mail list while building a second, commercial database from scratch. Whichever approach is taken, the result is a potentially lucrative asset.

Marketers who rent a campaign’s postal mailing addresses are free to send those people brochures for their natural testosterone boosters, or any other form of constitutionally protected communication, without revealing how they got the addressees’ information. With e-mail, the opposite is true. “You’ve got to receive the e-mail under the auspices of the list proprietor,” says Richard Viguerie, the Republican direct-mail pioneer. “Otherwise, it’s spamming.” Similarly, the purveyors of natural testosterone boosters, looking to maximize its potential customer base, can’t just pitch people through bogus accounts. They need a Herman Cain to send the e-mail for them.

This isn’t to suggest that Cain is personally taking meetings with the sales team at Natural Breakthroughs Research—or those at Franklin Prosperity Report and fixyourbloodsugar.com, to cite two other companies whose ads he has e-mailed. That’s why middlemen were invented. Cain, along with Huckabee, uses Newsmax, the right-wing media conglomerate. (Gingrich Productions opts for a firm called TMA Direct.) Founded a little more than 15 years ago as a single fringe website and built with early funding from Richard Mellon Scaife, Newsmax now publishes a main, free site that sometimes ranks as the most trafficked political URL on the Internet, as well as a suite of smaller, paid newsletters. To leverage its reach and pad its balance sheet, it also places ads for e-mail lists like Cain’s and Huckabee’s (National Review and Rasmussen Reports are clients as well), whose members fit comfortably into Newsmax’s demo: staunchly conservative and “mostly men, mostly 50-plus,” says Matt D’Lando, a vice president for business development.1

Representatives for Cain, Huckabee, and Newsmax all declined to disclose how much the ads are bringing in for the former candidates. But a back-of-the-envelope tally using rates Newsmax posts on its site works out as follows: At $36 per thousand list members for an ad filling an entire e-mail, and no fewer than 33 such ads sent last year, Cain made more than $420,000 from e-mail ads in 2013—minus Newsmax’s cut and the costs of maintaining his list. For Huckabee, whose list is nearly twice as long as Cain’s and commands a rate of $43.25 per thousand, the rough haul is north of $900,000. And those figures don’t include the separate, lower fees that Cain and Huckabee collect for embedding smaller sponsored teasers in editorial messages.

Calabrese argues that questioning the dubious nature of the products and services relayed through the promotions amounts to elitism. “I have no reason to think [an advertiser] is not a legitimate company just because it falls into a category a lot of people would snicker at,” he says, putting the onus on skeptics to prove that there is, in fact, no “1 WEIRD SPICE THAT DESTROYS DIABETES” and that recipients who respond hopefully to “THIS UNCLAIMED $20,500 CHECK YOURS? (SEE IF YOU QUALIFY)” will inevitably be disappointed.

Though the owners of e-mail lists can reject an advertiser that Newsmax sets it up with, Calabrese, who holds that veto power at Best of Cain, can’t recall a time he has needed to. Newsmax “does a really good job of vetting,” he says. D’Lando adds that, while the company makes efforts to screen out blatant fraudsters, any transaction that results between the e-mail subscriber and the advertiser is, of course, buyer beware. “Once somebody clicks on it,” he says, “that’s not our legal responsibility.”

Not every Cain, Gingrich, or Huckabee e-mail subscriber is a dyed-in-the-wool supporter. There must be some Republican voters who signed up out of curiosity and haven’t bothered to unsubscribe. (There is definitely at least one left-leaning reporter.) But if you’re a true believer, you are probably on your guy’s list. You bought into his message during the campaign. You thought he should be president! And so maybe you’re just a little more likely to buy something that you learn about through him. Especially if the “consistent income for life” or “financial transaction the gov’t can’t track” might alleviate some of the apprehension that Cain, Gingrich, and Huckabee—always talking about how the whole country is falling apart—seem so attuned to. It’s not a coincidence that these e-mail schemes have taken off on the right wing, where anxiety is a widely traded commodity and where Rush Limbaugh’s frequent on-air plugs of various advertisers and Glenn Beck and his gold coins have already blurred the line between authority figure and pitchman.

Cain, Gingrich, and Huckabee almost always take care to include caveats in the e-mail ads they send, spelling out that the sponsors’ statements and claims “do not necessarily reflect my views.” That specific language comes from Huckabee’s disclaimer, which is more extensive than the others’, perhaps because he’s now thinking about running for the White House again. (This may also help account for why Rick Santorum just uses his 2012 campaign e-mail list to send out press releases and announcements about upcoming speeches he’s happening to give in Iowa—the only improbable pitch he can be caught delivering is a Santorum presidency.) Yet, for all the feints toward propriety, the e-mail ads keep coming, and boundaries keep getting pushed.

Among marketing wizzes, there is a lot of excitement these days over so-called native advertising, which, in short, are digital ads that manage not to feel like ads at all. For example, a onetime White House contender might write his followers about a meeting he recently had with a “longtime friend and investment guru,” a man named John Mauldin, who publishes a financial newsletter under the banner “YIELD SHARK.” It costs $99 a year to subscribe to the tip sheet. At the time, its latest edition advised snapping up shares of Sturm, Ruger & Co., confident in the knowledge that even as wide-scale gun control was doomed, the mere threat of it was driving up firearms sales. The ex-candidate told his e-mail list that he’d done them a favor. He’d convinced Mauldin to give them a copy of “YIELD SHARK” for free, so they could check it out for themselves.

The e-mail, which carried no disclaimer, landed in inboxes on September 7. “I’M DOING SOMETHING I HAVE NEVER DONE BEFORE,” read Newt Gingrich’s subject line. Here’s betting it won’t be the last time an ex-candidate does the same, so long as the money is there.

Ben Adler, a reporter for Grist and correspondent for Columbia Journalism Review, covered the 2012 Republican campaign for The Nation.

- In this seminal Baffler article, Rick Perlstein provides an excellent history of Newsmax’s email marketing efforts and the broader enterprise of “mail-order conservatism,” writing: “The strategic alliance of snake-oil vendors and conservative true believers points up evidence of another successful long march, of tactics designed to corral fleeceable multitudes all in one place—and the formation of a cast of mind that makes it hard for either them or us to discern where the ideological con ended and the money con began.”