Many conservatives are marking the War on Poverty’s 50th anniversary with a predictable mix of contempt and distortion. A case in point is “The Fifty-Year War,” an article by the editors of National Review, which declares “the number of Americans living in poverty is higher today than it was in 1964, while the poverty rate has held steady at just under one in five.”

Are more Americans living in poverty today? Sure. But in 1964, less than 200 million people lived in the U.S. Today, more than 300 million do. In other words, the population as a whole has increased by more than half.

Has the official poverty rate hovered around one-in-five since that time? Yes. But it has fluctuated. And, as most experts will tell you, the official poverty rate fails to account for safety net supports like food stamps, housing vouchers, and the Earned Income Tax Credit program. An alternative poverty measure, developed by Columbia University researchers and designed to capture these effects, shows that poverty has indeed fallen. See the graph below, from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Note that even this measure understates the progress, because it does not count the impact of government-provided health insurance, particularly Medicare and Medicaid, both of which took effect in 1966.

The real story about the War on Poverty is both more nuanced and more positive than the right's caricature. You’ll find it in recent accounts by Annie Lowrey, Tim Noah, and Derek Thompson—and in a Russel Sage Foundation book put together by Martha Bailey and Sheldon Danzinger. To summarize and (grossly) simplify, programs designed simply to provide money or benefits have worked well, particularly for the elderly and children. Programs designed to realize more complicated goals, like developing better skills, haven’t. A shift in the structure of benefits, in order to reward work and penalize dependency, boosted the supports for the employed but took away some for the unemployed.

Of course, poverty rates depend a great deal on the economy. But just as the broad-based prosperity of the 1960s helped explain that era’s dropping poverty rates, so the rising inequality of more recent decades help explain why, despite the existence of so many public programs, so much poverty remains. Henry Aaron, the senior fellow at Brookings, put it well in an e-mail: “The War on Poverty has not realized its hopes. But it was swimming against a very fast flowing current toward inequality, at least since the mid-1970s.”

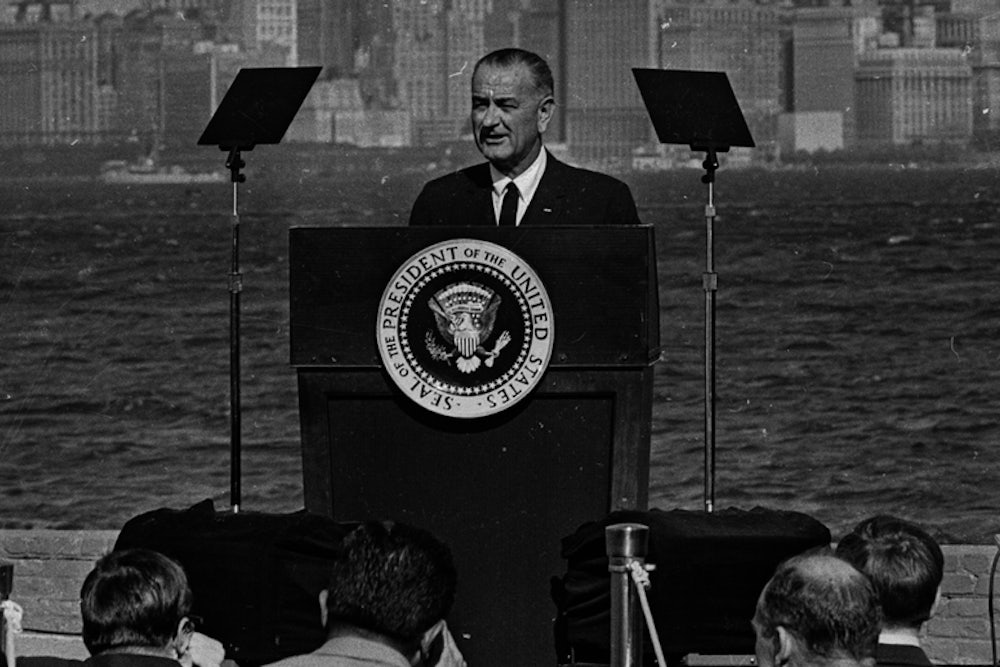

Elsewhere in the New Republic, Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute offers three lessons liberals can take away from the War on Poverty. I’d add one more. In his famous speech 50 years ago today, President Lyndon Johnson promised an “all-out,” “unconditional” war on poverty—and he promised that the country could “win” it. Although Johnson never said the U.S. would eradicate poverty, that was the implication. And that’s pretty much impossible to do. You can vanquish another country on the battlefield. You can’t really vanquish part of the human condition. Even Scandinavia has poor people—although, lord knows, the level of deprivation is much lower.

Lofty goals are fine, but the real test of policy is whether it achieves meaningful progress. And it’s a test we should apply to all policies. The Environmental Protection Agency’s plan for new power plan regulations might not stop climate change, but they could slow it. The Affordable Care Act might not eliminate medical bankruptcies, but it could reduce their incidence. The War on Terror might not end terrorism, but it could render the threat far less potent.

Of course, all policies have their trade-offs, whether it’s higher taxes or distortions to the market or threats to liberty. When it comes to the War on Poverty, whether the upsides justify the downsides has as much to do with values as empirical evidence. But if you dismiss the War on Poverty simply because poverty is still too high, then you are not making a serious argument.