In 1923, “a fourteen-year old from Chicago,” Judith Mackrell notes in her new multi-biography-cum-sociohistorical-examination, “tried to gas herself because ‘other girls in her class rolled their stockings, had their hair bobbed, and called themselves flappers,’ and she alone was refused permission by her parents.” Such drastic measures were certainly not common among flapper fangirls, but the spread of hair chopping, cigarette smoking, Charleston dancing, and all around unladylike behavior was indeed pervasive, both in the United States and abroad. But Mackrell’s book, which is far more interested in the genesis of the trend than its impacts, often forgets that although the flapper craze may have originated with the Chanel-wearing revelers at Gatsby-esque parties, it trickled all the way down to the finger-waving teenagers headed to the local dance.

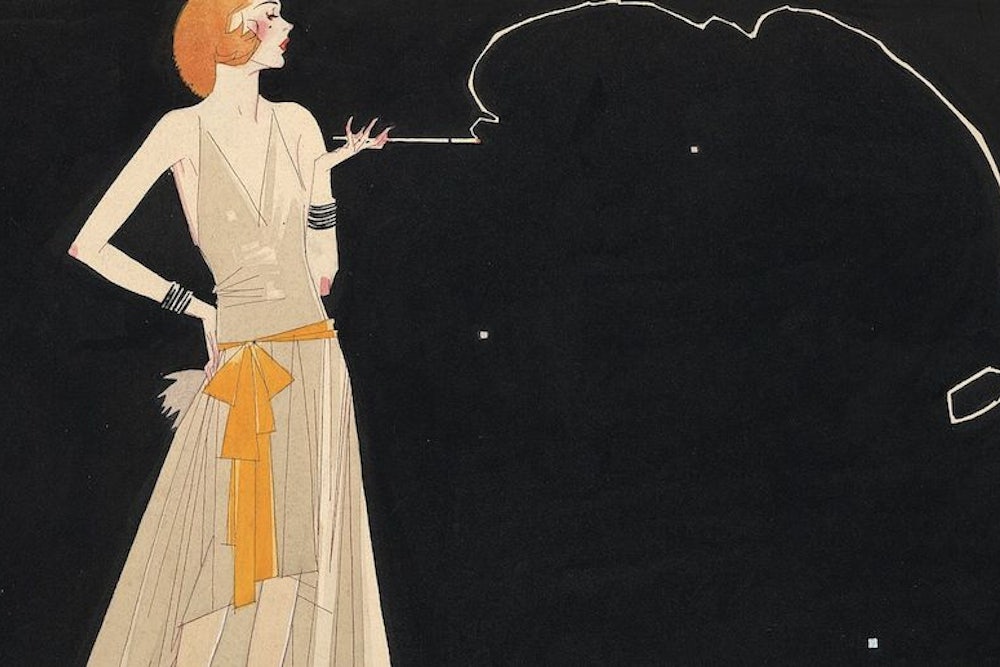

Flappers is a multi-pronged biography of the aristocrat Lady Diana Cooper, heiress-turned-actress Nancy Cunard, Georgian belle Tallulah Bankhead, art deco painting phenomenon Tamara de Lempicka, dancing sensation Josephine Baker, and Zelda Fitzgerald (who defies adjectival description). Each portrait chronicles its subject’s rise to stardom, pinnacle of success, and eventual fall from favor. It quickly becomes apparent, however, just how easily one story (with the exception of Josephine Baker’s truly atmospheric rise) could substitute itself for the others. Much like the champagne-soaked and cocaine-fueled parties blurred together for London and Paris’s Bright Young Things, so too do Mackrell’s wild, reckless, beautiful (and always, always stylish and thin) subjects. The bathtub-hostessing, hissy-fit throwing, and late night dancing is wonderfully rendered, but eventually grows as repetitious for the reader as it did for the flappers themselves. Though as individuals the women are (mostly) fascinating totems of an extraordinary age, Mackrell’s description of these six women as “dangerous” applies more readily to how recklessly they treated their own bodies and relationships than to the waves they made among popular culture. If flapperdom matters now, that’s because it deeply mattered then, but beyond the swells of screaming theater-goers and unnamed miscellaneous party guests, the masses are left unstudied.

Flappers’s largest contribution is that it reminds us that modern celebrity-worship is nothing new, that another pretty young thing is always waiting in the wings, that each new generation ushers in its own interpretations of rebellion and idolatry. But in the end, it remains unclear how epoch-making the flappers really were. And ultimately, Mackrell’s material may have rubbed off on her writing style: It’s a witty, beautiful, stylish tale with very little substance behind its shine.