If you liked your old skimpy health plan, you may not be able to keep it. But now you can get a new, somewhat skimpy health plan instead, at least for a little while.

That’s a rough translation of an Obamacare policy change that the Administration announced on Thursday. The change, first reported by Louise Radnofsky of the Wall Street Journal, represents yet another effort to help people about to lose their existing insurance policies, usually because those policies do not comply with the Affordable Care Act’s standards for benefits and pricing. Those old policies left out major benefits, were sold only to people without pre-existing conditions, and so on.

As you know, plan cancellations have been a source of tremendous controversy—and, for the president, immense political grief. Some estimates have suggested several million people received these cancellation notices. The vast majority of those people have already found new coverage, either directly through insurers or through one of the Obamacare exchange websites, according to the Administration. While some are paying more money, others have discovered that the new policies are cheaper—or, at least, are grateful for the extra protection. Lucia Graves of National Journal wrote about some of their stories the other day.

But some people still haven’t found insurance. Administration officials think, based on conversations with state regulators and insurers, that about half a million people fall into this category. That's half a million people who could, because of the individual mandate, face tax penalties because they have declined to get affordable coverage.

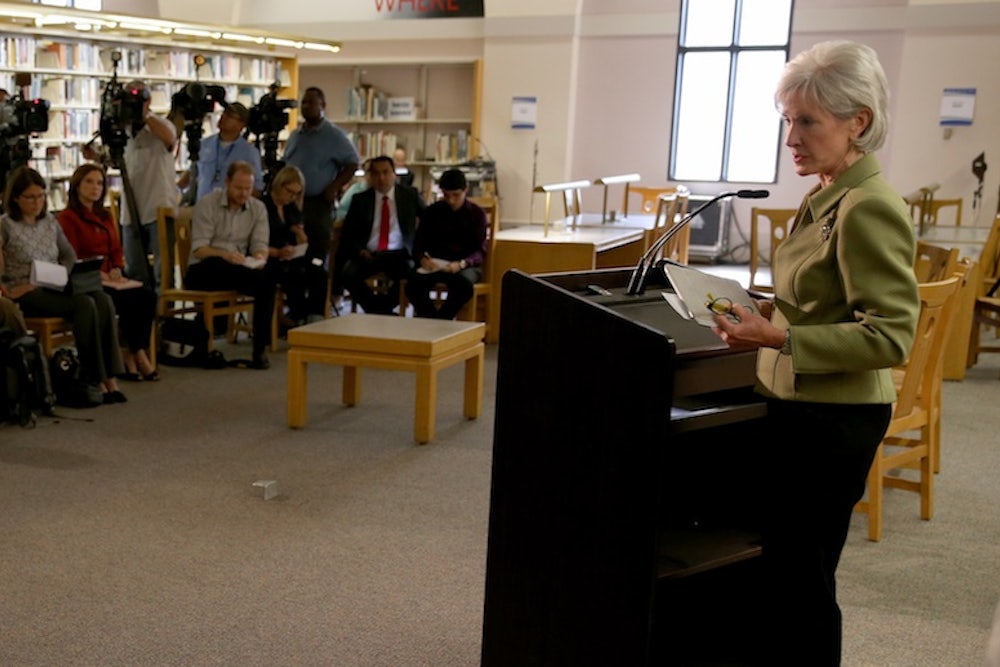

Now, however, people with cancelled policies have a new option. The individual mandate has always contained a hardship exemption: If you qualify for it, you don’t have to pay the penalty and you have access to the cheaper, slightly less comprehensive catastrophic insurance plans otherwise available only to people under 30. The only question with the hardship exemption has been who gets it. The law gives the administration flexibility over that question and, on Thursday, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius announced that it would apply to people who just lost their policies and are unable to find replacements that cost the same or less money.

HHS made the announcement by posting a guidance and sending a letter to a half-dozen more conservative members of the Senate Democratic caucus. And neither document answers all of the relevant questions, like how strictly the government will apply the new criteria or for how long this exemption will last. (Administration officials say it will be temporary.)

Conceptually, making the change is not so different from allowing more people to have grandfather protection for their existing coverage—after all, it’s basically telling people who have bare-bones coverage now that they can take out bare-bones policies next year. And imposition of the individual mandate was always supposed to be a gradual process. The financial penalty starts out relatively low, but will increase in 2015 and 2016. The administrative flexibility over the hardship exemption was designed to give the administration some leeway over enforcing the mandate, particularly early on, in order to ease the transition to a new and reformed insurance market. (The Massachusetts reforms, which were a model for the Affordable Care Act, also included a hardship exemption and called for increasing penalties over time.)

Administration officials don’t seem to think many people will take up this new option. They are probably right about that. Catastrophic policies aren't dramatically different in coverage from the "bronze" policies, which cover 60 percent of the typical person's medical expenses and comply with all Obamacare requirements. But if you buy a catastrophic policy, you’re not eligible for federal tax credits. If you buy a bronze policy, you are. As a result, most lower- and middle-income people would probably still find the bronze policies a better deal.

Still, some people—primarily, the one who don't qualify for subsidies—will opt for the catastrophic policies because they will be moderately cheaper. And some people will opt not to get insurance at all. That will mean fewer people in good health paying premiums for the exchange policies. That's a potential problem for insurers, who count upon those premiums to offset the medical bills of people in poor health. (For health policy wonks: The catastrophic policies are an independent risk pool, separate from other policies in the exchanges. So for every person who selects one of those policies, that's one fewer person putting premiums into the larger pot of money for the exchange policies.) There’s also a danger that, as Ezra Klein points out, the administration will come under more pressure to pull back on the mandate for other people. “This latest rule change could cause significant instability in the marketplace and lead to further confusion and disruption for consumers,” said Karen Ignani, president of America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Yes, insurers say those sorts of things all the time. And this singular change probably won’t cause serious, irreparable harm, any more than any of the previous ones did. The number of people whose behavior changes is likely to be small and the new system is more resilient than most people realize. But even minor changes can become major if there are enough of them.

Note: This item has been updated. As a friend reminds me, even the catastrophic plans under Obamacare aren't that skimpy. They still cover all essential benefits, for example, and the actuarial value really isn't much different from bronze plans.