As if Detroit hadn’t endured enough pain last night with Justin Tucker’s outrageous last-minute 61-yard field goal kick to give the Baltimore Ravens the win on "Monday Night Football," today comes more evidence that the city is getting taken to the cleaners in its bankruptcy proceedings. The Wall Street Journal’s Matthew Dolan and Emily Glazer reported today that the city has already paid more than $28 million in legal and consulting fees related to the bankruptcy process—and that its emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, has said that could rise to as much as $100 million. By another metric, as the Detroit Free Press’ Stephen Henderson noted in September, the city had, as of that date, already approved $62 million in contracts related to the proceedings.

Everyone in a suit, it seems, is getting in on the act. But they assure us that they’re going easy on the city and not charging nearly as much as they would if they were conducting business as usual. You half expect them to claim a charitable deduction for deigning to come to town.

There are the lawyers, reports the Journal:

In recent months, Jones Day, the city's law firm in the case and Mr. Orr's former employer, has billed the most: $10.6 million for five months of work, including a $3.8 million bill for October alone, records show. The city also paid the firm $3.7 million for work completed before the city's bankruptcy filing, according to city documents.

"We have written down a bunch of time worth millions of dollars," said David Heiman, one of Jones Day's lead attorneys on the case.

And the boutique investment bankers:

Rising fees drew notice from the presiding judge recently when a lawyer for retirees in the bankruptcy case described the hiring of a $175,000-a-month consultant as typical for a corporate bankruptcy.

"I'm sure that is so, but we're talking about public money," said U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Steven Rhodes, who on Monday approved a contract for the city to pay the investment bank, Lazard Ltd., to advise a committee representing the city's 23,500 retired workers on financial and restructuring issues. A Lazard managing director said the fee is appropriate given the firm's expertise in restructuring work.

Heck, there are even the art appraisers:

The bills have grown rapidly in recent months. From the day after the bankruptcy filing until Dec. 6, the city paid consultants $10.8 million, documents show. That includes $1 million to the restructuring firm Conway MacKenzie Inc. and $238,000 to Christie's Appraisals Inc., which evaluated city-purchased works at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Christie's called the payment amount "fair compensation for the project." A Conway MacKenzie spokesman said the firm declined to comment.

But don’t worry, there’s someone to watch over all this. Who of course is being paid, too:

Poring over the bills is the fee examiner, Robert Fishman, who is supposed to decide which ones are appropriate and reasonable. Charging as much as $600 an hour, his firm has billed the city more than $66,000 for two months of work. Mr. Fishman declined to comment on the case.

Now granted, people deserve to be paid for the work they do. And set against other big bankruptcies, Detroit’s bills aren’t even that enormous—Alabama’s Jefferson County has paid $25.7 million over two years, General Motors Co. coughed up $110 million, and the U.S. administration of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. ran up about $2.2 billion.

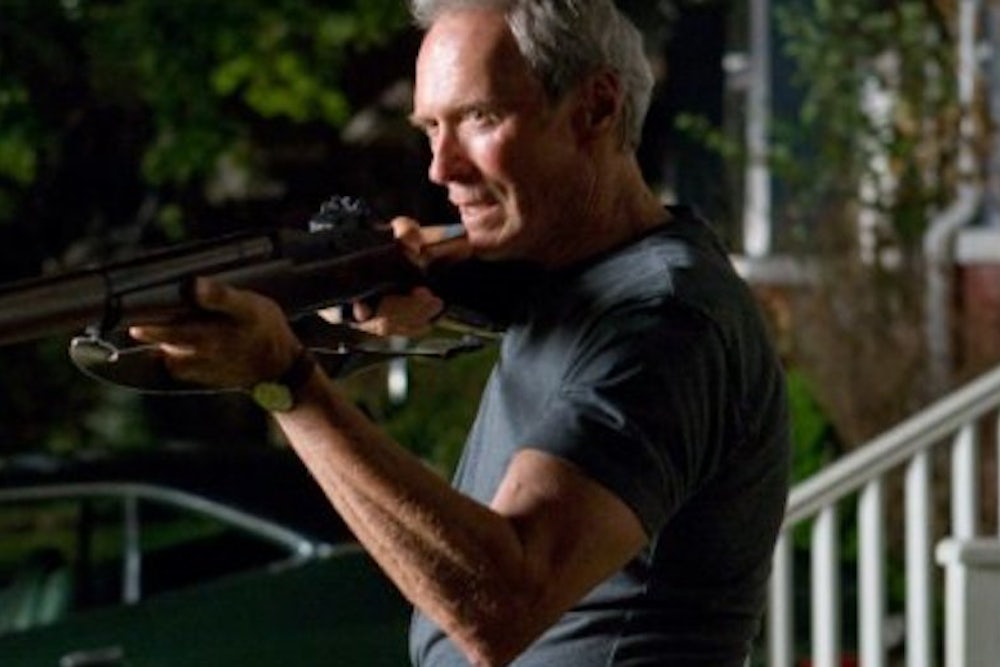

But seen in another light, the fees are deeply galling, ironically so. For years, the rest of the country—that is, its government and business elites—turned a blind eye to the stunning deterioration of what was not all that long ago one of our largest and most prosperous cities. And now that the city has reached the point of actual bankruptcy, who should swoop in to make a tidy sum off of the proceedings but members of those same coastal upper echelons. The gap between the country’s thriving cities and regions and its lagging ones has been widening in recent years, and the Detroit bankruptcy is not only highlighting this, but is exacerbating it: the rapidly dwindling reserves of the city are flowing to Jones Day partners in Los Angeles and Christie’s headquarters at Rockefeller Center. Really, where’s Clint Eastwood when you need him?