"The Meaning of Conrad"

August 20, 1924

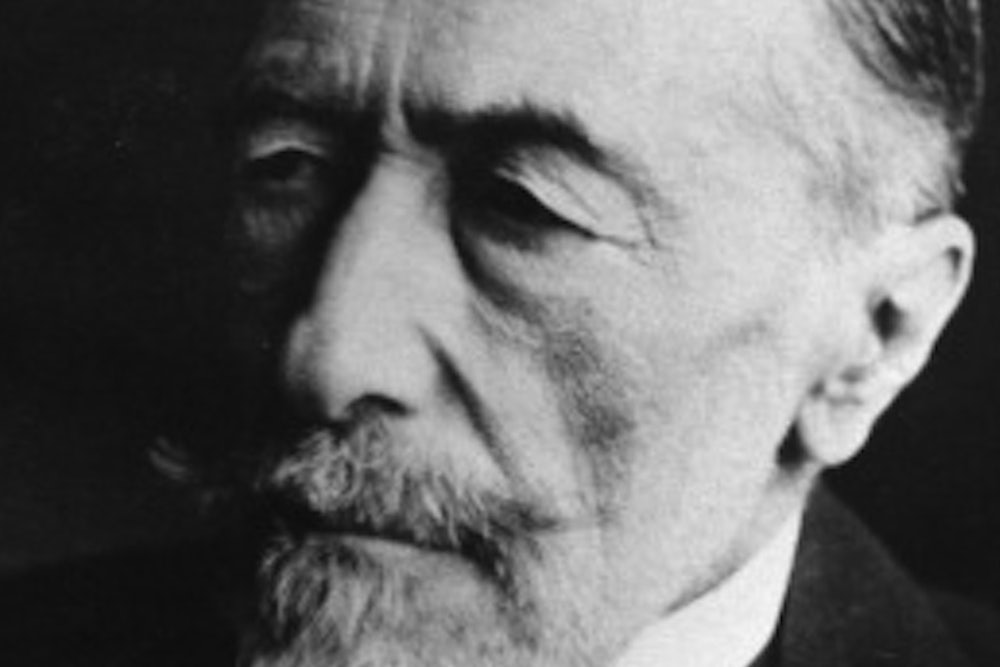

Except Thomas Hardy no English man of letters could have given by his death such historic importance to the year 1924 as Joseph Conrad. Born in 1857, a year after Bernard Shaw, Conrad began his literary career late, in 1895, with Almayer's Folly. This was the year of Stevenson's death, and of Hardy's virtual, and almost of Meredith's, retirement from fiction. Shaw had not yet published Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant, and Galsworthy, Bennett, and May Sinclair were still below the horizon. Thus Conrad found his predecessors, except for Henry James and George Moore, leading the stage or already gone, and himself the first of the new generation to occupy it. In twelve years he had published ten books including The Nigger of Narcissus, Lord Jim, Youth, Nostromo, and The Secret Agent which are distinctive of his first period. "The writing of these books," wrote Mr. Galsworthy in 1908, "is probably the only writing of the last twelve years that will enrich the English language." And there were still to come the two most elaborate and characteristic of Conrad's performances, Chance and Victory.

The place of Conrad in the literary movement of the time has been often indicated—his inheritance from both romantic and realistic progenitors, which enabled him to add to romance (the poetry of circumstance, as Stevenson defined it) the realism of human experience, and to make realism significant as the poetry of character. It must not be forgotten also that 1895 marked a definite advance in the revival of mysticism. Ibsen was writing the last will and testament of realism in When We Dead Awaken, and a new cabinet of European letters was being formed under the presidency of Maurice Maeterlinck. Whether Conrad ever read it or not, Maeterlinck's preface to the first collected edition of his plays states the program which Conrad's work was to illustrate. "High poetry," says Maeterlinck, "is composed of three elements: First, verbal beauty; next, the passionate contemplation and depiction of the what really exists around us and in ourselves; and finally...the idea that the poet makes of the unknown in which float the beings and things that he evokes, of the mystery which dominates them and presides over their destinies."

How completely Conrad lends himself to this analysis is obvious. In verbal beauty, in mastery of the beautiful material of language and the swaying of it in powerful and haunting rhythms he is supreme. Again, the passionate contemplation and depiction of reality was the beginning of his literary workmanship. He has told us how the sight of Almayer, "forty miles up, more or less, a Bornean river," set his mind working on the problem which required seven years for its solution. His first inspiration was visual. "He (Almayer) was moving across a patch of burnt grass, a blurred shadowy shape with the blurred bulk of a house behind him, a low house of mats, bamboos and palm-leaves with a high-pitched roof of grass." But the interest shifts to character. "If I had not got to know Almayer pretty well," Conrad wrote later, "it is almost certain there would never have been a line of mine in print." What happened in the case of Almayer is typical of Conrad's method. First it is the sensuous appeal which takes him, and no one has ever rendered more acutely and strikingly the effects of darkness, light, heat, rain, wind, forest, river, sea, and of men and things exposed to these elements. But Conrad's realism is never authoritative and photographic. Appearance immediately becomes subjective, and to make the method more explicit the experience is often transmitted though the consciousness of a third person. This is the characteristic procedure in Conrad's undoubted masterpieces, Lord Jim, Chance and Victory.

It is the third element, and in Maeterlinck's view the most important, which has given rise to most dispute in regard to Conrad's position—"his idea of the unknown in which float the beings and things that he evokes, of the mystery which dominates them." That he is acutely conscious of this mystery there is no doubt—it is as present to him as to Maeterlinck himself. Mr. Wilson Follett has called attention to Conrad's frequent preoccupation with the physical presence of somebody or something hidden, as in The Secret Sharer, the symbolism of which tends to bridge the gap between appearance and reality. But what idea does he give of this unknown? Mr. Mencken thinks it merely the crass casualty or cosmic implacability of Mr. Hardy's universe. He sees all of Conrad's heroes "destroyed and made a mock of by the blind incomprehensible forces that beset them," and the title Victory "an incomparable piece of irony," But surely this is not the emphasis which Conrad himself places upon his world. It is true his heroes are not conquerors in the material sphere, but the significant thing is that they continue to strive. The theme which Conrad presents most constantly is one of affection, devotion, protection, tested by danger, by the fury of nature and by the craft of savage men, calling out courage, loyalty, endurance, sacrifice. The object of this devotion may be a child, a ship, a woman. OFten his theme is the loyalty between men of different race, of white men to brown, or brown to white. It is hard to miss the meaning of Lord Jim's sacrifice, as in expiation alike of his own long ago faithlessness and the treachery of men of his own race he goes before Doramin to die by his hand—a witness to the imperial truth that the test of a man's fitness to rule his fellow men is his willingness to die, not only for them and with them, but by them.

If Conrad had not presented this theme so constantly, his own comment, sparse as it is, would give us a definite idea of his moral index of the world. "The world," he says in Reminiscences, "rests on a few very very simple ideas, so simple that they must be as old as the hills. It rests notably amongst others on the idea of Fidelity." It is because the sea emphasizes the dependence of man upon man and loyalty to the ship as a condition of survival against the hostility of nature that Conrad justifies it as the medium of his tales. "The sea," he writes in The Shadow Line, "is the only world that counted, and ships the test of manliness, of temperament, of courage and fidelity—and of love." It is the fidelity to the claims of race which leads him to dedicate Rescue to Hugh Clifford, "who among the Malays whom he governs, instructs, and guides us the embodiment of the intentions, of the conscience and might of his race." And finally his own creed embodies in words which Maeterlinck himself might have used the sense of the business of the artist to promote the union of mankind in the presence of the unknown, which becomes an ennobling rather than a mocking, terrifying, or crushing conception, through the participation of all men in its mystery.

"He [the artist] speaks to our capacity for delight and wonder, to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives; to our sense of fellowship with all creation—and to the subtle but invincible conviction of solidarity that knits together the loneliness of innumerable hearts to the solidarity in dreams, in joy, in sorrow, in aspirations, in illusions, in hope, in fear, which binds men to each other; which binds all humanity—the dead to the living, and the living to the unborn."