There’s a real case that Chris Christie is the front-runner for the 2016 Republican nomination. That’s pretty remarkable: He’s for gun control, hails from the northeast, pals around with the president, struggles to call himself a conservative, and doesn’t even hold 20 percent in the polls. He has solid name recognition, but at this point it’s safe to say his appeal is limited.

To be sure, Christie has the ability to broaden that appeal among GOP voters. He hasn’t committed heresy on abortion or Obamacare, like Mitt Romney had before 2012. Still, Christie could easily become a glorified factional candidate without great appeal outside of the Northeast and moderate suburbs, someone who can only win in a protracted struggle against some other factional candidate—someone like Rand Paul or Ted Cruz, who might lack support beyond the South or Conservative caucuses. From that perspective, Christie’s mainly the frontrunner because his main primary opponents are also, ultimately, factional candidates.

But what if there were a candidate with a broader natural base? Right now, the Republican Party is an increasingly factional place, divided between north and south, establishment and grassroots, Tea Party Conservatives and practical Conservatives, religious right and business, libertarians and populists. All the same, it remains possible for a mainline conservative to win the party’s mainstream, marginalize both the tea party and the moderates, and win without a lengthy struggle. Someone like George W. Bush, a born again Christian from Texas with a Harvard MBA, could unite the traditional business and religious wings of the party and, in doing so, win primaries in 44 states. That’s exactly the candidate that the likes of Christie, Paul, Cruz—or most other Republican hopefuls—should fear.

Luckily for the GOP’s factional stars, it’s tough to be a mainline Republican. The broadly appealing conservatives, like Bobby Jindal or Marco Rubio, earn their broad appeal at the expense of anyone’s passion: They’re no one’s first choice, and they start without an electoral base. To win, they would need to stand out—in debates or on the stump, or in the so-called “invisible primary,” where a candidate can rally the party establishment and build the campaign apparatus and media attention necessary to elevate themselves in the minds of voters. But the party’s establishment is also factionalized—no candidate succeeded in uniting it in either 2008 or 2012, even though Romney was a clear establishment favorite.

Early this year, it seemed like Rubio had a real chance to pull it off. The young, charismatic senator from Florida was an establishment savior, the physical manifestation of their political vision for winning national elections by appealing to Hispanics and young voters. He’d do so, they envisioned, without compromising on the party’s core religious and business policies—just immigration reform and Tea Party rhetoric. But immigration reform crashed and Rubio seemed unprepared to compete at the highest levels. His numbers have declined; he’ll struggle to regain the trust of the establishment.

So far, Rubio and Jindal look like they’re auditioning for the role of 2016’s Tim Pawlenty—a candidate the mainline establishment wished could take off, but someone who didn’t have the chops to win either Iowa or New Hampshire, states where the Tea Party and moderates are at an advantage. Perhaps the most obvious alternative to Rubio is Jeb Bush. But it’s unclear whether the “compassionate conservative” message still plays with Republican primary voters, let alone whether Bush will run.

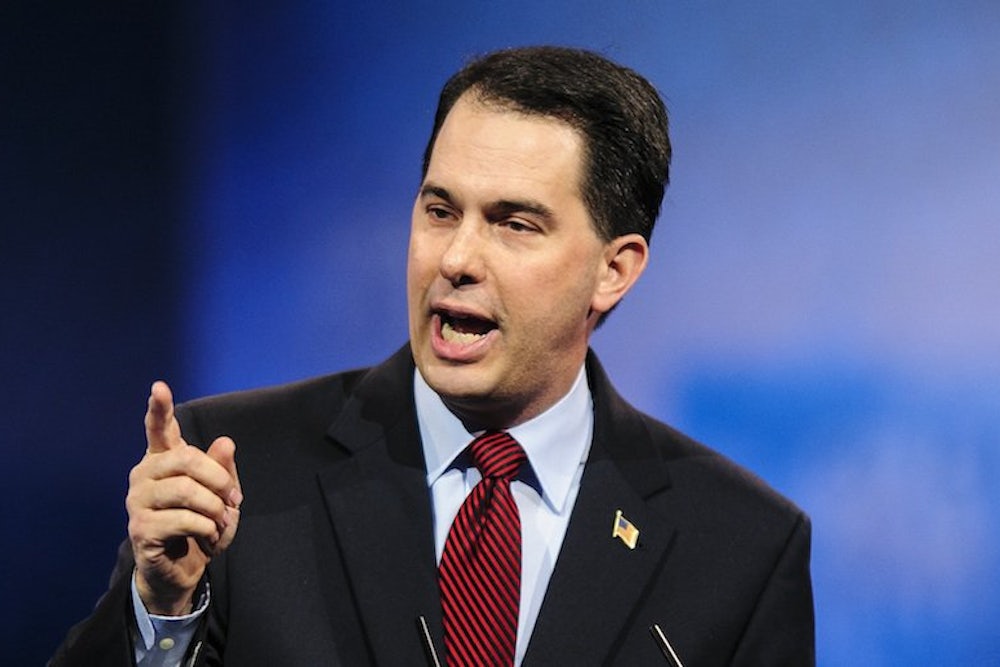

There’s another potentially unifying mainline conservative, though, and he lurks in Madison. Scott Walker, the battle-hardened governor of Wisconsin, is the candidate that the factional candidates should fear. Not only does he seem poised to run—he released a book last week—but he possesses the tools and positions necessary to unite the traditional Republican coalition and marginalize its discontents.

Walker has the irreproachable conservative credentials necessary to appease the Tea Party, and he speaks the language of the religious right. But he has the tone, temperament, and record of a capable and responsible establishment figure. That, combined with Walker’s record as a reformist union-buster, will appeal to the party’s donor base and appease the influential business wing. Walker’s experience as an effective but conservative blue state governor makes him a credible presidential candidate, not just a vessel for the conservative message. Equally important, his history of having faced down organized labor and beaten back a liberal recall effort is much more consistent with the sentiment of the modern Republican Party than Jeb Bush’s compassionate conservatism. Altogether, Walker has the assets to build the broad establishment support necessary for the fundraising, media attention, and organization to win the nomination. He could be a voter or a donor’s first choice, not just a compromise candidate.

The other mainline conservatives possess some of Walker’s characteristics, but not all. He’s more compelling and presidential, with more gravitas than Rubio or Jindal.

To a certain extent, Walker is benefitting from caution and obscurity. Last year, I could have easily written that “Rubio could be a voter or a donor’s first choice, not just a compromise candidate.” Perhaps Walker will disappoint, too. After all, Pawlenty shared Walker’s impressive electoral record in competitive states, but apparently lacked the chops to pursue the presidency. There’s no way to know whether Walker’s prepared until he runs.

But even though Walker’s political skills remain an open question, there are reasons why he might be a stronger candidate on paper. For one, he’s a more experienced politician—and the fact is that political skills and instincts are learned and honed under tough circumstances. By the time Walker’s wins reelection—which I expect—he will have won three competitive statewide contests in a tilt-blue state, under three different circumstances. He will have done so while campaigning and governing as a conservative. There are very few politicians who can claim as much.

It’s also easy to imagine Walker catching fire in Iowa. The language of the religious right comes naturally for Walker, who often begins his speeches by thanking God or his supporters for their prayers during the recall. And ultimately, the Iowa caucuses privilege the religious right more than the Tea Party or any other form of modern conservatism. According to the 2012 entrance polls, 57 percent of Republican Caucus goers were Evangelical Christians—Rick Perry and Rick Santorum won a combined 46 percent of their vote, with Newt Gingrich and Michele Bachmann adding on another 20 percent. Sixty percent of 2008 Republican Iowa Caucus-goers were Evangelical Christians, and Huckabee won 46 percent of their vote.

Walker won’t campaign as a culture warrior, like Santorum or Mike Huckabee. But overt religiosity would give Walker a considerable edge over the typical mainline conservative, much as it did for George W. Bush. It would even give Walker an edge over an ultraconservative Tea Party candidate who doesn’t speak the language of the religious right: It’s not a coincidence that Huckabee and Santorum won Iowa, or that Santorum won Iowa’s “strong Tea Party supporters” by a 13-point margin. And Walker’s status as a culture ally, not a culture warrior, would give him broader appeal throughout the party—especially given his temperament and reformist pedigree. Unlike Huckabee and Santorum, he’ll play outside of the South.

Walker’s Midwestern roots would also be helpful, and not just because he should play well in Iowa, which neighbors his home state. If Santorum or Gingrich had the organization necessary to compete for the nomination, they would have needed to win Midwestern states like Michigan and Ohio. Incredibly, both states were extremely close—mainly because evangelicals represented between 42 and 49 percent of the electorate. Romney prevailed by racking up massive margins in metropolitan areas—a blueprint Christie will likely need to follow. But Walker stands a real chance of competing with Christie, blow for blow, in the relatively moderate but still conservative Republican turf around Detroit, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, while winning the countryside by a large margin.

Of course, Walker's not even assured of winning reelection. And Christie has a head start in the invisible primary. But on paper, Walker’s a very credible candidate—even a great one. Mainline conservatives with hesitations about Christie seem likely to give Walker a serious look. Ultimately, he’d need to take advantage of that opportunity, and prove he’s as strong in practice as he is in theory, by performing well in the debates, building a capable campaign, and building support in Iowa. But so far, there’s no reason to think he can’t. If he does, he’ll be the Republican frontrunner.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Michele Bachmann's first name.