To understand why Senate Democrats took the historic step they did Thursday to allow a simple majority vote to confirm many presidential appointments, it helps to look beyond Washington, to put what’s been going on here in a national context.

In Texas just recently, Attorney General Greg Abbott, the likely Republican nominee to replace Rick Perry as governor, explained in a court brief that the redistricting plan passed by Texas Republicans had not been racially discriminatory, as alleged by the U.S. Department of Justice, which is challenging on similar grounds the state's new Voter ID law. Rather, Abbott argued, Republicans had simply been trying to crush the state’s Democrats, who, it so happens, are disproportionately non-white:

"In 2011, both houses of the Texas Legislature were controlled by large Republican majorities, and their redistricting decisions were designed to increase the Republican Party's electoral prospects at the expense of the Democrats," read a court brief filed by Abbott. Abbott also qualified the tactics, noting that partisan districting decisions are still constitutional, despite "incidental effects on minority voters." The brief cites Hunt v. Cromartie, a South Carolina case in which it was decided that "[a] jurisdiction may engage in constitutional political gerrymandering, even if it so happens that the most loyal Democrats happen to be black Democrats and even if the State were conscious of that fact."

Two years earlier, the majority leader of the Wisconsin state Senate, Scott Fitzgerald, explained with equal candor in an interview with Fox News that the move by his fellow Republican, Gov. Scott Walker, to decimate the state’s public employee unions was motivated by a desire to weaken a key pillar of the Democratic Party:

If we win this battle, and the money is not there under the auspices of the unions, certainly what you’re going to find is President Obama is going to have a much difficult, much more difficult time getting elected and winning the state of Wisconsin.

The Senate Democrats’ 52-48 vote Thursday was met with predictable laments about the resulting loss of bipartisan comity. The vote “ensures an escalation of partisan warfare,” declared the home page of The Washington Post. “So you didn't think partisanship in the Senate could get worse? It just did,” tweeted USA Today’s Susan Page. "Filibuster Vote Marks Escalation in D.C.'s Partisan Wars," frets an NPR.org headline.

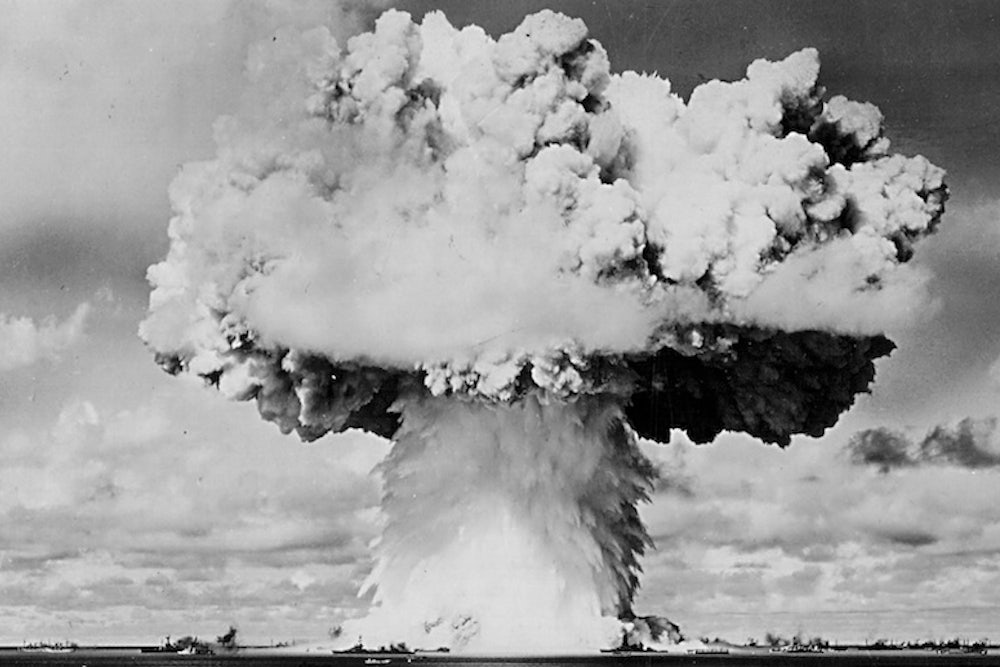

But such laments willfully overlook that we have long since entered an era of total partisan warfare that would be difficult to escalate any further—it’s as if a moral philosopher showed up at the Second Battle of the Marne in 1918 fretting about the use of automatic weapons. “I realize that neither party has been blameless for these tactics. They developed over the years,” Obama said after the vote. “But today’s pattern of obstruction, it just isn’t normal. It’s not what our founders envisioned. A deliberate and determined effort to obstruct everything, no matter what the merits, just to refight the results of an election is not normal, and for the sake of future generations we can’t let it become normal.” The laments are particularly curious considering how proudly—almost admirably!—candid Republicans have been in recent years in embracing whatever tactics they can to advance their team’s prospects, whether it comes diluting the influence of Texas’ black and Hispanic voters or eviscerating the organized-labor funding base of Wisconsin Democrats or, yes, maintaining an edge on the crucial D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals that lay at the center of the current filibuster showdown.

That, after all, is what set this judicial nomination fight apart from those before it: Republicans’ striking opennness in declaring that they were blocking President Obama’s three judicial nominees not out of any plaint with their qualifications or ideology, but simply because they did not want to give Democrats a majority of appointees on that D.C. appeals bench, which rules on so many key regulatory issues, from the new health care law to carbon emissions standards. As it now stands, the court is split evenly between Republican and Democratic appointees, while Republicans maintain an edge among the pool of substitute judges that are frequently called on to fill in. Some Senate Republicans and conservatives made a half-hearted attempt to couch their blockage of the nominees as a budget matter, arguing that the court’s workload didn’t justify any more judges. But in general, they were as blunt as could be in their motivation: they simply were not going to allow Obama and the Democrats to reap one of the age-old benefits of winning two elections in a row, being able to appoint judges of their choosing to the federal courts and thereby tilt their makeup slightly in their favor. “They want to control the court so it will advance the president’s agenda,” said Mitch McConnell in explaining why Republicans would do everything they could do prevent that control—as if the Democrats’ desire for such influence in the third branch of government was somehow untoward or authoritarian (indeed, they went so far as to equate Obama's filling established slots on the court with Franklin Roosevelt's attempted packing of the Supreme Court by adding extra seats to it.) This followed the equally undisguised attempt to keep Obama from implementing his agenda by simply refusing for months to confirm nominees to head executive departments, such as the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whose actions carried no official weight without a confirmed director. If there was any doubt that such a strategy bore the traces of John Calhoun, the famous father of a famous senator put it to rest with a recent speech (in Richmond!) urging Republicans to adopt, yes, "nullification."

The legal historians note that opposition parties have long been more reluctant to confirm judicial nominees to federal courts that were in close partisan balance. That is, the norm of presidents being able to select qualified people of their choosing to the federal bench had been in the process of being undermined for some time now amid the feints and quailing by both sides regarding this or that nominee’s qualifications or alleged extremity (with good reason, in some cases: among the judges allowed onto the D.C. appeals court as part of the Senate's "Gang of 14" compromise in 2005—a deal whose spirit was breached by this fall's filibuster of the three Obama nominees—was Bush nominee Janice Rogers Brown, who has called liberal democracy a form of “slavery” and post-New Deal regulations “the triumph of our socialist revolution.”)

From the standpoint of this history, the sheer brazenness of the Senate Republicans in laying bare their partisan intent this time around was refreshingly honest, in a way, as was Greg Abbott and Scott Fitzgerald’s acknowledgment of their plans to pulverize the other side. But it also had the clarifying effect of upending the norm around presidential appointments far more completely than all previous rounds of gamesmanship had done. It left Democrats no choice, really, but to upend a norm of their own. You can have unwritten norms in an atmosphere of bipartisan comity, but without the latter, you can't have the former. And bipartisan comity not only left the barn long ago; it had been tracked down and shot behind the woodpile. It’s long past time to stop mourning it and start to reckon with what its absence means for a constitutional system that was not designed for parliamentary-style, ideologically-coherent parties of the sort we are left with today, facing off across a muddy field.