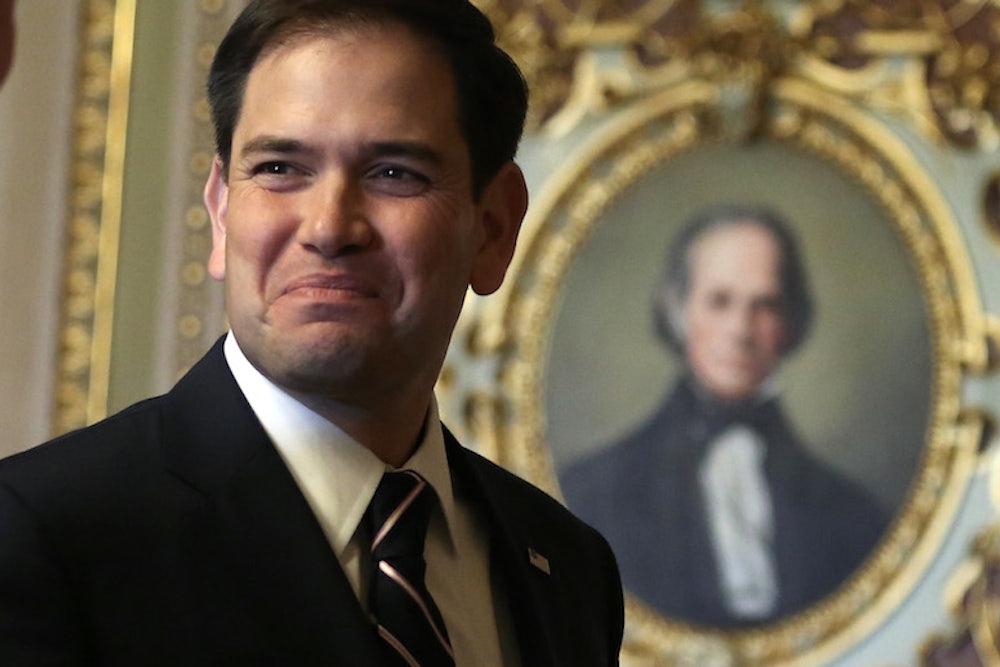

Marco Rubio has had a rough 2013. He began the year as potentially the next Republican presidential nominee. But he spent the ensuing ten and a half months trying to please everyone who could get him there.

Take immigration. To even begin to describe his contortions on the attention-getting issue is nearly impossible because he has flip-flopped so many times. The gist is that he went from a supporter of comprehensive immigration reform to an opponent of the same, but freighted both stances with caveats and qualifications. The same dynamic shaped Rubio’s approach to the debt ceiling and the government shutdown. No doubt scared that he had turned off primary voters with his immigration vacillating, the theretofore temperate senator abruptly decided to get as close as possible rhetorically to Ted Cruz. The move was so absurd and strained, and so out-of-character, that he ended up looking even more craven than he had during the immigration debate.

The whole sorry exercise has made plain to friend and foe that there is no man or woman in the United States Senate who is more calculating than the junior senator from Florida. Rubio clearly desires to please the right wing of his Party while also showing centrists and establishmentarians (and the people who fund GOP presidential campaigns) that he is no ideologue, and is in fact a man who cares primarily about getting things done. The result has been that he has stained his reputation, and seen his standing fall among Republican primary voters.

So what’s a bright young presidential hopeful to do when his political fortunes hit a losing streak? Straight out of the consultants’ playbook, Rubio decided the time was right for that heartiest of political-aspirant traditions: The Great Big Important Foreign Policy Speech. Rubio grabbed a friendly lectern at the American Enterprise Institute for 35 minutes to speak on America's role in the world.

It was not exactly a break with recent history. Anyone who has followed Rubio's career, or even his flailing 2013 performance, could probably have guessed that the talk would try to do two things: The first would be to find a middle ground among the possible 2016 primary contenders. And the second would be to speak in broad generalizations, so as not to be tied down by what other people refer to as convictions. And on at least one level, the exercise worked: The headline from the Politico story on the speech declared “Rubio neither hawk nor dove." Right down the middle!

A close read of the speech, though, reveals a lot more about both the state of the GOP and the state of Rubio’s convictions. The overenthusiastic Politico headline references this part of the speech:

Meanwhile, at home, foreign policy is too often covered in simplistic terms. Many only recognize two points of view: “doves”, who seek to isolate us from the world, participating in global events only when there is a direct physical threat to the safety of our homeland; and “hawks”, who believe we should use our mighty military strength to intervene in response to practically every crisis.

These labels are obsolete. They come from the world of the past.

The time has now come for a new vision for America's role abroad: one that reflects the reality of the world we live in today.

This excerpt actually struck me as somewhat Obama-esque, imitating as it does the president's annoying habit of laying out the positions of his opponents with caricatured disdain, and then proclaiming himself part of the thoughtful center. Who knew that "hawks" believe we should intervene in "practically every crisis?" (Also, note to Rubio: you need a new speechwriter. "The world of the past"?)

Politico claims, probably correctly, that with this part of the speech Rubio "did not name names, but he was clearly articulating a blueprint different than that of both Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Gov. Chris Christie (R-N.J.), potential rivals in the 2016 presidential race who occupy opposite ends of the GOP’s foreign policy spectrum." This certainly fits with Rubio's eagerness to find a comfortable position, but it leaves out the upshot of the rest of the talk: Even though Rubio frames it as a middle-ground address, the speech is actually a full-throated defense of hawkishness. All it lacks, of course, is any sort of prescriptive, hawkish vision.

As Rubio states, "Some on both the left and the right try to portray our legacy as one of an aggressive tyrant constantly meddling in the world’s crises. But ask around the world and you’ll find that our past use of military might has a different legacy." (Again: Phrases like "but ask around the world" are the reason I suggested he find a new speechwriter). Rubio continues with more platitudes:

Sometimes military engagement is our best option. And sometimes it’s our only option.In those instances, it must be abundantly clear to both our allies and our adversaries that we will not hesitate to engage unparalleled military might on behalf of our security, the security of our allies and our interests around the world.

Diplomacy, foreign assistance and military intervention are tools at our disposal. But foreign policy cannot be simply about tactics. It must be strategic, with a clear set of goals that guide us in deciding how to apply our influence.

Of course, he never defines what any of these words mean, or what following them would entail.

Rubio then turns to the Obama administration. Even an all-things-to-all-people Republican doesn’t need to pull any punches here. Sure enough, Rubio takes a couple of shots at the president's lack of a clear vision regarding postwar Libya and Syria. But this is followed by: 'Now, clearly we can’t undo what’s been done. But we need to ask ourselves, “What can we do about this going forward?”' A good question, which Rubio proceeds to not answer. On civil liberties, he merely notes that some Americans have "valid concerns" but offers nothing except praise for our intelligence programs.

He then goes through almost every region on earth, speaking platitudinously about all of them (“Our renewed focus on Asia does not need to come at the expense of our longstanding alliances in Europe. We can and must do both”), before ending by saying, "Despite the challenges we face here at home, America must continue to hold this torch. America must continue to lead the way."

In sum, Marco Rubio is pro torch-holding, and anti-obsolete labels.

And yet you can’t read the speech without being impressed. It is the perfect document of Rubio's soon-to-be-formally-initiated presidential campaign. He manages to appear fundamentally part of the Republican foreign policy consensus, to the degree it still exists. He tries to position himself to capture some of the Rand Paul isolationist energy. And he says not a single thing that would commit him to anything substantive were he to win the Republican nomination or become president.

Only in this sense is Marco Rubio's speech important.