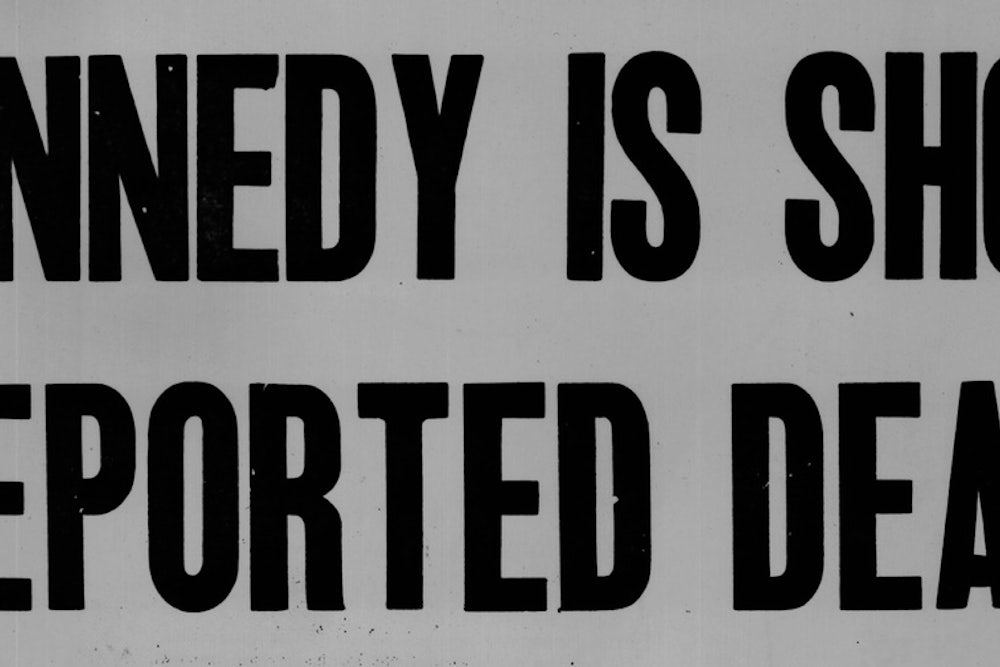

Pretty much all Americans over the age of 50 will reminisce this week about where they were when JFK was shot. They might remember in vivid detail and tell their stories convincingly—but, even if they have extraordinarily good memories, they might be wrong.

A study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that even individuals who can recall details from nearly every day of their lives since mid-childhood, thanks to an unusual condition called “highly superior autobiographical memory” (HSAM), can be convinced that distorted or even completely false memories are true. The researchers recruited 20 people with HSAM and 38 with normal memories, and gave them a series of tests designed to measure their susceptibility to believing implanted memories. In one test, for instance, participants were asked whether they had seen the “well-publicized footage” of United Flight 93 crashing in Pennsylvania on September 11. (No such footage exists.) Twetny-nine percent of subjects with normal memories and 20 percent of those with HSAM reported that they had. In another test, after being shown a list of related words, 70 percent of people in both the control group and the HSAM group wrongly believed they had seen a different (though similar) word.

This study adds support to the growing literature suggesting memories can be manipulated and even planted. This summer, neuroscientists at MIT succeeded in planting false memories in mice. And researchers have found that although Americans typically sound confident when they recall where they were and what they were doing on the morning of September 11, they remember fewer details with less consistency as time passes.