Last year, Bernie Kosar, the former Cleveland Browns star quarterback, seemed anything but fine. Throughout October and November, he sent a series of incoherent tweets; during a radio-show appearance in December, he slurred, shouted, and rambled until the hosts mercifully cut the segment short. Separately, Kosar confessed to suffering from depression, ringing in the ears, and insomnia. He was displaying the hallmarks of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the brain disease caused by repeated blows to the head. The 49-year-old Kosar had seen a platoon of doctors, but none of them could help.

Within a few weeks, though, everything had changed. On January 10, Kosar called a press conference and, standing before a room of Cleveland reporters, declared himself cured. The Browns winning the Super Bowl would have seemed more likely. But here Kosar was, smiling and confident. And the credit, he said, went to the square-faced man in a black t-shirt and tan blazer standing beside him: Dr. Rick Sponaugle.

CTE can only be diagnosed via autopsy, but Sponaugle explained how Kosar had visited his clinic in Palm Harbor, Florida, where the doctor used something called a “positron emission tomography scan” to figure out what was wrong with Kosar’s head. Details about the ensuing treatment were sketchy—Sponaugle delivers supplements through an intravenous drip, the formula for which is proprietary—but Kosar testified that, whatever was in the stuff, it worked its wonders in no time. “It was a gift from God to find this and feel like this,” Kosar told the journalists. “I see all the symptoms going away.”

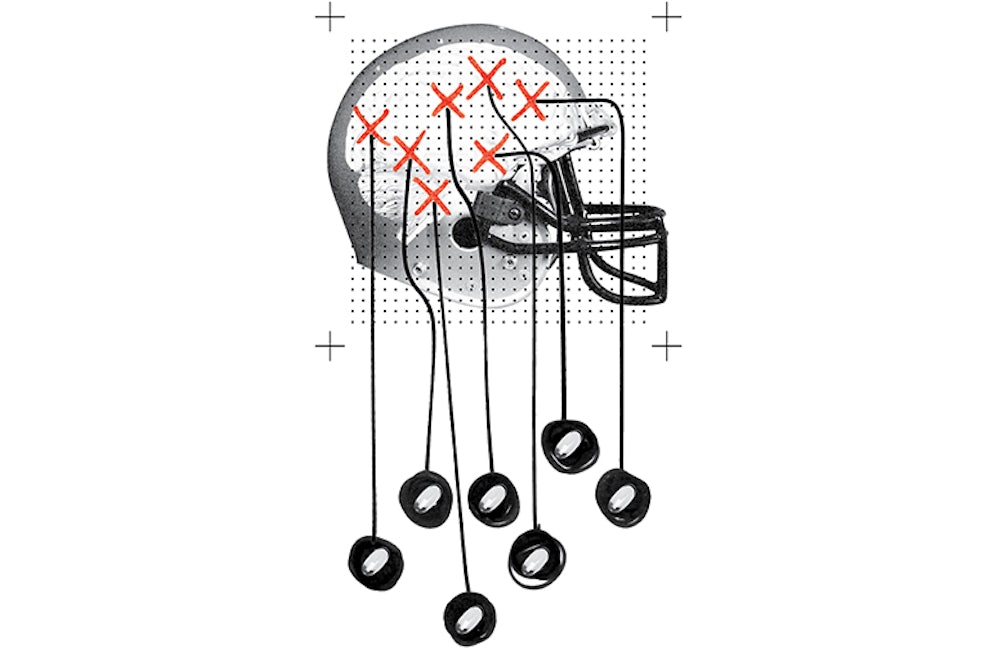

It’s hard to overstate what a fix for CTE would mean for football. More than ten years after the disease was first found in the brain cells of a prematurely dead former lineman, awareness of its risks is now widespread; earlier this year, 4,500 former NFL players sued the league for allegedly hiding the dangers of head trauma. The ex-athletes who suspect they’re suffering from the condition face a cruel paradox. During their careers, they learned to will their bodies to amazing feats—and to equate giving up with moral failure. They get banged up, then get their shot of Toradol and are good to go. But with CTE, there is no fighting their way back to health. “Once the brain tissue is lost, it’s gone,” says Robert Stern, a neuropsychologist at Boston University’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy and a leading CTE researcher. “These are neurodegenerative diseases, with no known ways of slowing or stopping them.”

“The neurologists that I saw, the only thing they had to offer was, ‘Get your affairs in order.’”

Yet halting the ravages of CTE and undoing the damage of individual concussions is exactly what a small but increasingly sought-out group of doctors is telling vulnerable ex-players they can do. Sponaugle—whose board certifications are in anesthesiology and addiction medicine—is just the most prominent member in an emerging subspecialty that claims hundreds of ex-athletes among its clients. To the medical establishment, these doctors and their unproven procedures show that football’s brain-injury crisis has entered its snake-oil phase; in The Washington Post, the head of the American Psychiatric Association, Jeffrey Lieberman, went so far as to label one practitioner’s methods as “the modern equivalent of phrenology.”

“It is really an emotional thing,” says Stern. “There are so many people out there who are hurting and do not deserve to be given false hope.”

Kevin Turner, a former fullback with the New England Patriots and Philadelphia Eagles, was 41 years old in 2010 when he was diagnosed with ALS, another neurological disorder plaguing ex-football players. “The neurologists that I saw, at this point I had seen three or four, and the only thing they had to offer was: ‘Get your affairs in order,’ ” he says. He got an appointment with Sponaugle instead. Recently bankrupt and newly divorced, the father of three paid thousands of dollars to give the doctor a shot: “I felt like, what do I have to lose?” Turner says an Internet search originally led him to Sponaugle, though the doctor is not shy about prospecting for business. Kosar was the first of Sponaugle’s 20 or so NFL clients to share their story, but—at Sponaugle’s urging—many of his non-athlete patients have gone public with their tales of magical cures, providing fodder for infomercials and attracting the attention of Suzanne Somers, Ricki Lake, and Dr. Phil.

Sometimes, the pitches to former players happen in person. A few years ago, Sponaugle spoke at a gathering of NFL alumni. Daniel Amen, a psychiatrist, was in attendance as well and says he has spoken at five or six such gatherings overall. Football players make up about half of the 300 current and former professional athletes Amen treats. The author of more than two-dozen books, including the best-selling Change Your Brain, Change Your Life, he employs methods similar to Sponaugle’s: brain scans followed by custom-designed therapies and secret-recipe supplements. He charges $3,500 for an initial consultation and around $175 per follow-up. The supplements run another $200 or so per month.

Where some doctors use potions, others rely on far-out machines. Ted Carrick, who calls himself a chiropractic neurologist, gained attention a couple years ago when NHL star Sidney Crosby credited him for helping him recover from a series of devastating concussions. Among the treatments Carrick used: strapping Crosby into a space-camp looking gyroscopic chair and spinning him, upside-down, around and around and around. Carrick says the wait to enter his clinics in Dallas, Texas, and Marietta, Georgia, can stretch to a year. When patients do finally get in, he charges them $1,000 per day. Most stay one to two weeks. Insurance companies do not pick up the tab.

Any doctor who actually comes up with a proven cure for CTE, says Stern, “should win the Nobel Prize.” Since these practitioners’ methods haven’t been scientifically verified, how can they be sure their treatments work?

“That is the dumbest question you can ask,” says Sponaugle, who claims he doesn’t have the time or resources for the proper studies. “You find another medical center that has all those people going public and looking totally different. Find it and I’ll kiss your butt in Times Square on New Year’s Eve. . . . When you’re pioneering, you always get this. The proof is in the patient.”

Turner, the former fullback, says he stopped seeing Sponaugle after about a year and a half. Though he believes the doctor’s techniques slowed the development of his ALS, they did not reverse the disease’s course. His muscles now defy him when he attempts a task as simple as opening the refrigerator. He can barely speak. Kosar, for his part, has returned to the erratic behavior that can accompany CTE. (Efforts to reach him for this story were unsuccessful.) In late September, Solon, Ohio, police arrested him on suspicion of DUI.

As part of the regimens they prescribe, many of these alternative doctors include general wellness practices like eating right and exercising, which can leave patients feeling better on their own. But for the desperate, even a temporary improvement can feel like a miracle. After Kosar’s press conference, he contacted NFL commissioner Roger Goodell to spread the gospel of Sponaugle. A phone call was set up between the doctor and a league medical adviser. While the medical establishment has weighed in heavily against these alternative brain treatments, the NFL is perching itself on the fence. “We do have an open mind about the less traditional, alternative, and complementary medicine approaches to concussion,” Dr. Richard Ellenbogen, the co-chair of its Head, Neck and Spine Committee, told me. “We simply await the scientific evidence that accompanies them before enthusiastically endorsing them for use in NFL athletes.”

Under the terms they worked out with the league in August, the players who sued the NFL over its safety practices are set to share $765 million. Sponaugle expects the deal to be a boon for business. “I had guys that signed up for testing—and all of a sudden the NFL talked about settling, and they called back and said, ‘We’ll wait,’ ” he says. “I’ve actually had players say, ‘If you fix my brain, I won’t be able to win. I won’t get any damages.’ ” He expects that, once their checks arrive, those players will start coming to see him, “unless they’re all talk.” Meanwhile, Sponaugle is already having trouble keeping up with demand. He has five nurses and an additional doctor staffing his busy clinic, but, he says, “I’m looking for more.”

Jason Schwartz is a senior editor at Boston Magazine.