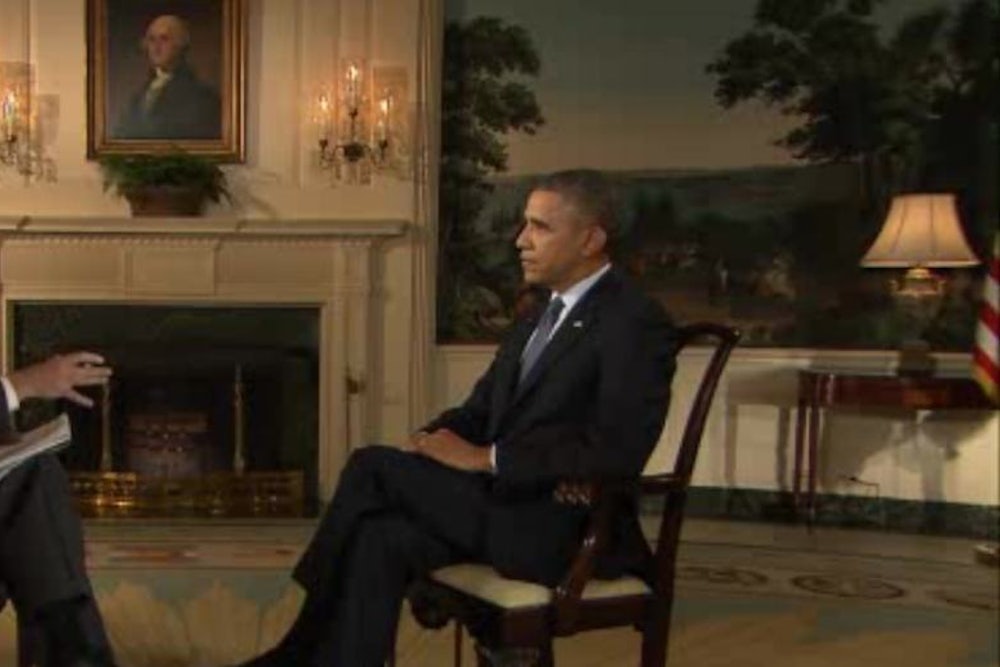

In an interview Thursday with NBC News' Chuck Todd, President Obama apologized to Americans receiving cancellation letters from insurers—and promised to investigate whether his administration could do something to help them. The apology is appropriate. Obama made sweeping promises that he should have qualified or at least explained in more detail. While most people will get to keep their plans next year, some won’t. During the interview, Obama stressed that he and his allies did their best to minimize disruption when they designed the Affordable Care Act. That much is true. The law would be much, much simpler if its architects hadn’t tried so hard to leave existing employer policies in place. But the promise that everybody could keep his or her plan went too far. It wasn’t possible to make that ironclad guarantee and Obama should not have issued it. As Andrew Sullivan wrote yesterday, before the president spoke:

He made a decision in a polarized climate to over-simplify to the point of near-deception. I don’t think it’s outright deception because the plan does indeed mean that large numbers of people will not be forced to switch plans so much as upgrade some. But he still said something that was untrue and he underlined it with a “period”, meaning there were no caveats.

The controversy, though, isn’t simply about what Obama said. It’s about what’s happening to the people getting those letters. Many will be better off: They will switch to plans with lower premiums or stronger benefits. And don’t forget: Some people who pay higher premiums for better coverage will end up spending less in the long run, because insurance will cover more of their medical bills. But many people will clearly be worse off. By now, you’ve read some of their stories. And if you’re the type of person who reads this publication, chances are good you actually know somebody in this situation. They tend to be relatively affluent—the kind of people too wealthy to receive the law’s generous subsidies. Now they are responsible for the higher prices of better coverage, which can be thousands of dollars a year. They are not happy. Who can blame them?

But getting them help would not be easy to do. Remember, the higher prices they face are a direct consequence of the improvements that Obamacare makes to the non-group insurance market, which has been famously dysfunctional. These people will be paying more precisely because insurers must now provide coverage to anybody, even people with pre-existing conditions, and because insurance must offer real protection. These are reforms the American people support overwhelmingly—and with good reason. Via Ezra Klein:

There's been an outpouring of sympathy for the people in the individual market who will see their plans changed. As well there should be. Some of them will be better off, but some won't be.

But, worryingly, the impassioned defense of the beneficiaries of the status quo isn't leavened with sympathy for the people suffering now. The people who can't buy health insurance for any price, or can't get it at a price they can afford, or do get it only to find themselves bankrupted by medical expenses anyway have been left out of the sudden outpouring of concern.

A more ambitious health care reform would have, at the very least, minimized premium increases for the currently insured—by providing consumers with more generous subsidies or more aggressively controlling the price of insurance. Liberals called for such measures when the Affordable Care Act was moving through Congress and they would support them now. But doing those things would require some combination of substantially more government spending and a lot more regulation. If those proposals didn't succeed when Nancy Pelosi ran the House, you can safely assume they won't succeed now that John Boeher is in charge. That’s why officials and lawmakers are likely to contemplate narrower changes.

Which is fine, except that every conceivable option has its own potentially serious complications. Obamacare has a “grandfather clause,” which allows insurers to keep offering policies that were in place before the law’s enactment (in March, 2010) and haven’t changed since. Officials or lawmakers could, for example, decide to alter the clause, so that it applied to plans in place as recently as last month. But enacting such a change presents a challenge: It's not clear, for example, whether it would require new legislation. Meanwhile, insurers have already sent out the cancellation notices and made arrangements with state regulators. In some cases, they are making business decisions they were bound to make at some point anyway. It’s not clear that the carriers would, or could, simply go back to offering the same plans to people who had them. Even if insurers wanted to do it, that would have effects on who goes into the new marketplaces—potentially reducing the influx of healthy people whose premiums would offset the cost of people with more serious medical conditions.

Can officials and lawmakers figure out some way to make a fix like this, or some other adjustment, work? Possibly. Among other things, Obamacare has several provisions (like “reinsurance”) designed to ease the transition into a newly reformed market. But it would be a very messy solution. And before weighing the tradeoffs of any such move, it would be nice to get some more perspective on exactly how big the problem really is—and what kind of response, if any, it really warrants.

So far such perspective has been lacking. Stories of people facing higher rates are all over the media, but many of these stories aren’t what they seem—and occasionally they are the very opposite of what they seem. Clearly some people really will have to pay more for insurance, without getting substantially better benefits in return, but it’s difficult to know how many people or what precise circumstances they face. The problems of the federally run websites make the real situation even more ambiguous, since many people reacting to the higher prices have no easy way to investigate their insurance alternatives. What we need is a sensible conversation about who’s really worse off because of the reforms, and in what ways. Hopefully Obama’s apology makes that conversation easier to have.

Update: I changed "probably" to "possibly" when describing viability of various patchwork solutions, just to emphasize that the downside of any "fix" could easily outweigh the upside.

Visit NBCNews.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy