Edward Snowden’s disclosures and subsequent government declassifications have prompted a wave of proposals to retool the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (“FISA”). Some of these proposed revisions are new; others merely reprise older ideas which were put forward earlier in Congress, as recently as 2012.

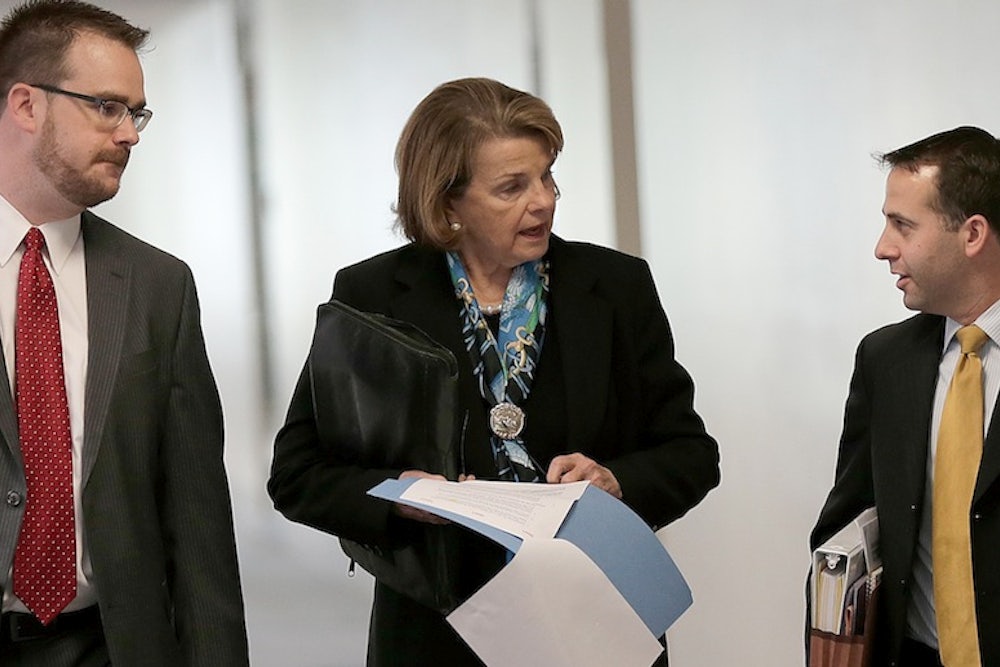

Rare bipartisan alliances have coalesced during the debate—ones that have more to do with attitudes towards government surveillance and which committees members lead than they do with party affiliation. On one side, you’ll find the leaders of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Chairwoman Dianne Feinstein and Ranking Member Saxby Chambliss. On the other are the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Patrick Leahy, and former House Judiciary Chairman James Sensenbrenner—along with Senators like Ron Wyden, Richard Blumenthal, Mark Udall, Al Franken, Rand Paul and Mike Lee and a motley crew of House members too.

Broadly speaking, the pending FISA reform bills address one or more of the following major issues: the substantive reach of surveillance activities under the statute; the procedures used in the two FISA-created courts; the processes by which the courts’ judges are selected; and the transparency and reporting requirements governing surveillance under the FISA. Thursday, the SSCI approved legislation supported by Senators Feinstein and Chambliss; just before that, Senator Leahy and Rep. Sensenbrenner put forward a competing proposal. What follows is an overview of these and other bids to rework FISA.

The Substantive Scope of FISA

The SSCI bill—what we’ll call “Feinstein-Chambliss“—would affirm the legality of controversial NSA surveillance programs, while codifying in statute restrictions on access to and use of information gleaned from such programs. The legislation also would tackle what its authors see as a worrisome, surveillance-stopping scenario (or “collection gap,” to borrow the intel jargon), in which a foreign target crosses into the United States, but the government has not yet obtained a warrant authorizing continued eavesdropping.

Regarding the latter, the SSCI-approved legislation would permit, in exigent circumstances, continued surveillance of a non-U.S. person who has entered the United States, for 72 hours following the government’s recognition that this person is likely within the United States. During the 72-hour interval, the government could request a court order under traditional FISA to conduct further surveillance; alternatively, and in an emergency, the Attorney General could unilaterally certify that continued surveillance is required. But absent such certification or a court order, the government would be obliged to destroy information obtained after the 72 hour period’s lapse. This would effectively close the gap the government currently believes exists, avoiding a situation in which needed surveillance is unilaterally suspended at the moment the subject crosses into U.S. territory (a potentially critical moment in an investigation) but is then renewed some time later after the government has persuaded a judge to permit surveillance to continue. The provision permits a shorter collection timeframe than do existing emergency authorization provisions in other parts of FISA.

Compare this with the approach outlined by Senator Leahy. His bill was introduced Tuesday and co-sponsored by Representative James Sensenbrenner, along with 3 Senate Republicans, 13 other Senate Democrats, 40 other House Republicans, and 36 House Democrats. This marks the Senator’s second and most recent foray into FISA reform; his first would have raised the standard for orders issued under Section 215 of the PATRIOT ACT—the so-called “business records provision”—and thus, like the current proposal, would have effectively blocked the government from seeking orders compelling the production of bulk telephony metadata.

Section 215

Section 215, or the so-called “business records” provision, is well-known to Lawfare readers. It is the statutory basis for the NSA’s deeply controversial collection, on a mass scale, of telephony metadata—non-content information, like numbers dialed, call length, and so forth.

Feinstein-Chambliss would authorize bulk telephone metadata collection, though it does prohibit bulk collection of communications contents under the business records provision and it imposes stricter limits on access to collected metadata. It imposes in statute a retention period for collected metadata by the government of five years, and requires approval by the attorney general for queries of data older than three years old. It codifies the now-familiar requirement that NSA analysts must have a “reasonable articulable suspicion” (“RAS”) of a target’s association with international terrorism before analysts can query the agency’s metadata trove. Feinstein-Chambliss, moreover, writes into law a series of other issues previously handled in FISC orders: the number of individuals with access to collected metadata and the limits on the number of “hops” an analyst can make from an initial target, for example. NSA would, moreover, have to submit each of its RAS findings for U.S. persons to the FISC for review; should the FISC not approve those, it could mandate the destruction of that collection.

The Leahy-Sensenbrenner bill, by contrast, tightens the rules on the collection side of the Section 215 house, and in that respect departs from Feinstein-Chambliss. The bill’s main innovation is to impose a higher standard for obtaining an order under Section 215. To do that under Leahy-Sensenbrenner, the government would have to furnish to the FISC a statement of facts showing that sought items are “relevant and material” to an investigation conducted either to obtain foreign intelligence or to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities. The items in question must additionally “pertain” to one of the following: a foreign power or agent of one; the activities of a target who is a suspected agent of a foreign power; a person in contact with a known or suspected agent of a foreign power. The practical effect of this new, bucked-up legal standard? It would likely take the NSA’s metadata program off the table.

Other noteworthy odds and ends in Leahy-Sensenbrenner: it would prohibit the use of FISA’s pen register/trap and trace provision, or National Security Letters, from being used as means of evading strictures imposed by the bill’s revised standard for collection under Section 215. And, prior to obtaining FISC authorization to conduct foreign electronic surveillance (what many consider to be “traditional FISA”), Leahy-Sensenbrenner would have the government provide to the FISC either the identity of the target, or a description “with particularity” of the target. Last but not least, the legislation would sunset authorization for National Security Letters in June 2015; and realign the FISA reauthorization with much of the Patriot Act, thus allowing Congress to debate these programs all at once.

Section 702

Regarding Section 702 activities—for example, the compelled production, from U.S. social media companies, of posts and chats by foreigners believed to be abroad—Senators Feinstein and Chambliss also wouldn’t substantially touch the government’s collection powers. As before, their idea is to impose new access restrictions on collected stuff: that is, to require intelligence analysts to establish that the purpose of any query of collected data, using a U.S. person’s identifier, is to obtain foreign intelligence or information necessary to understand foreign intelligence. Records of those searches must, in turn, be retained, and made available to the DOJ, ODNI, Inspectors General, the FISC, and appropriate congressional committees.

Beyond attempting to restrict the collection of purely-domestic communications, Leahy-Sensenbrenner likewise largely leaves collection itself alone. But the legislation has more extensive access-restricting features than does Feinstein-Chambliss. The bill precludes analysts from searching for U.S. persons’ communications collected as a consequence of Section 702—save only for searches authorized by court order, those required when such a person’s life is threatened and the information in question is needed to help that person, or those authorized by consent. There’s also an explicit prohibition against searching a “collection of communications [using Section 702] in an effort to find communications of a particular United States person” to deal with the so-called “reverse-targeting” of U.S. persons. It also restricts the use of information obtained using a certification that the FISC determines does not meet legal requirements.

Takeaway: Feinstein-Chambliss would preserve bulk telephony metadata collection under Section 215, while adding back-end safeguards (either by establishing brand new ones, or codifying ones in use already) regarding access to the collected material. Leahy-Sensenbrenner would end bulk collection under Section 215, while imposing access restrictions of its own on business records collection. Both bills would tinker with the rules for accessing data collected pursuant to Section 702, with Leahy-Sensenbrenner seemingly calling for a more stringent regime.

FISC Procedure

The various legislative proposals currently on the table would alter two key procedural dimensions of the FISA: the manner in which federal judges get appointed to the two FISA courts, and the ex parte, non-adversarial nature of FISA court proceedings.

Adversarial Proceedings

Under current law, proceedings before the FISC and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review (“FISCR”) are non-adversarial, in that no party generally opposes the Department of Justice’s position during court proceedings. This need not be the case. When telecommunications companies get FISC orders to produce material, they can appeal them. But they generally don’t. And nobody routinely opposes government applications before the court on behalf of civil liberties concerns. That nearly all government applications to the FISC are ultimately approved serves as fodder for those who favor adjustments to the one-party system. And judging by the bills in play, there’s pretty much two ideas for doing so: the addition of a new “Special Advocate,” a lawyer who would argue in the public interest in FISC proceedings; or of an amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” when called upon by the court.

Feinstein-Chambliss would once again apply the lightest touch, so far as adversarial process is concerned. The bill would authorize the FISC and the FISA Court of Review to designate, when needed, one or more individuals to serve as amicus curiae; and it would authorize these amicus to “assist” during a FISC/FISCR proceeding, and to review court records in the course of doing so. The courts’ assignment power would be discretionary, and limited only by Article III of the Constitution and the needs of national security. Under Feinstein-Chambliss, the Attorney General would be informed whenever amicus has been appointed. The legislation, finally, would permit the court to request executive branch assistance in implementing its amicus curiae provision.

Under an earlier proposal from Senators Blumenthal, Wyden, and others, the President’s Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board would nominate five Special Advocate candidates, at least one of whom would be appointed by the Chief Judge of the FISCR for a renewable five-year term. Thereafter, the FISC would have discretion to appoint the Special Advocate in particular matters; the Special Advocate also would be empowered to ask the FISC to reconsider decisions, or to ask for the participation of amicus curiae. (The FISC would likewise retain its own unilateral amicus-appointing authority.) The Blumenthal bill would establish standing before the FISCR for the Special Advocate, as well as the Court of Review’s standard of review in appeals: de novo for issues of law, and clearly erroneous for questions of fact. The Special Advocate would also be entitled to appeal FISCR decisions to the Supreme Court, and move for public disclosure of FISA courts’ materials. The Attorney General would be able to challenge the disclosure motions.

The Leahy-Sensenbrenner proposal would do much the same as the Blumenthal bill, the only difference being that the Leahy-Sensenbrenner Special Advocate would be able to ask to participate in a FISC proceeding, and would receive access to all FISC and FISCR decisions issued.

One House alternative, sponsored by House Democrats Adam Schiff and John Carney, would authorize the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board to select a pool of attorneys who could represent the public in FISC litigation. The FISC would be required to appoint from the pool when the court engages in “a significant interpretation or construction of a provision of this Act, including any novel legal, factual, or technological issue or an issue relating to the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.” The public advocate would then participate fully in the proceedings, have access to all relevant evidence, petition for an order requiring the government to produce evidence, and request a rehearing or rehearing en banc.

Also in the House, the Democratic pair of Reps. Stephen Lynch and James Himes have a bill to create a “Privacy Advocate General.” Among other things, the latter would serve as opposing counsel to government on all FISC applications; could appeal decisions and request public disclosure; and would be appointed by the Chief Justice and the most senior Supreme Court Justice nominated by a President of different political party from the President who nominated the Chief Justice.

Picking the Judges

The judge-picking debate boils down to this question: is the FISC stuffed with judges of a particular, surveillance-friendly viewpoint? Feinstein-Chambliss and Leahy-Sensenbrenner both suggest an answer, in that they don’t deal with the appointment of judges at all. But other legislative proposals explicitly take up the issue, and urge changes to the selection process.

Currently, the FISC and the FISCR judges are appointed by the Chief Justice of the United States. The FISC must have eleven judges in total, who in turn must represent at least seven of thirteen federal judicial regions, or “circuits.” Of that eleven, three must reside within twenty miles of the District of Columbia. FISC judges serve a single, seven-year term. The appointment process was controversial when Congress debated the original FISA, in the 1970s, and it remains so today.

Nowadays, critics worry that the Chief Justice’s appointments to the FISC are heavily weighted toward conservative, Republican-appointees. That premise is itself a matter of at-least historical debate; one study of Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s FISC selections concluded that these were a fairly-representative sample of the larger pool of federal judges; a Brookings study of the Chief Justice’s appointment power highlights factors beyond the nominating president’s party affiliation that the Chief Justice considers when making his selections.

At any rate, the primary judge-diversifying proposal has been put forward by nine Democratic Senators, including Sens. Wyden, Udall, and Blumenthal. Their bill would require greater geographic diversity at the FISC, by insisting its judges hail from each circuit. (The change would mean increasing the number of FISC judges, something the group explicitly acknowledges.) As for the selection process, this would include a formal nomination by the chief judge of each circuit court to the Chief Justice. Should the Chief Justice reject a circuit’s selection, then the chief judge would propose two alternatives from his circuit, one of whom the Chief Justice would have to select. The appellate-level intelligence court, the FISCR, would see its judges selected through the same process above—the only difference being that the FISCR judges would be subject to approval by five of the Supreme Court’s Associate Justices.

Another bill, co-sponsored by Congressmen Adam Schiff and several Democratic colleagues (along with Republican Ted Poe) would require presidential nomination and Senate approval of FISC judges.

Takeaway: a modest consensus has emerged among the main players in the reform-the-FISA debate, reflecting comfort with adding another party to FISA’s ex parte litigation mechanism. It’s just a matter of how comfortable with what sort of adversarial process. At one end of the spectrum, Reps. Lynch and Himes would require the government to be opposed by a special advocate in all FISC proceedings. A less far-reaching change can be found in Leahy-Sensenbrenner, which says that a Special Advocate can—but need not—elect to take part in FISC litigation. Still less far-reaching bills would vest in FISC the power to order the Special Advocate’s participation in significant cases. At the furthest end of the comfort spectrum is Feinstein-Chambliss, which would vest discretion in the court to appoint a less-clearly-adversarial third party: an amicus.

If there’s any kind of consensus emerging on matters related to the appointment of judges, it may be to do nothing—as evidenced by the fact that neither Feinstein-Chambliss nor Leahy-Sensenbrenner would alter judicial selection in the two FISA courts at all.

Disclosure and Transparency

Another area of developing, if only rough, consensus: the desirability of stronger disclosure and transparency provisions.

Already, the FISA has a number of mandatory reporting rules, which are sprinkled throughout the statute’s various provisions. Broadly speaking, the Attorney General must submit semiannual reports to House and Senate intelligence committees and the Senate Judiciary Committee, on the aggregate number of requested and granted (and in some cases, modified) orders for electronic surveillance, physical searches, pen registers and trap and trace devices, and persons targeted. The Justice Department must likewise report on significant FISC legal interpretations of Section 702, FISC materials containing significant legal interpretations, and targeting and minimization procedures and activities. The government is required to submit to those committees annual reports regarding orders for tangible things.

Since the Snowden leaks, the FISC has sought to provide more information about its activity than is currently mandated by FISA. FISC Chief Judge Reggie Walton has begun releasing data on the number of applications receiving “substantive changes” between submission to the court and grant of the order: in the last quarter of FY2013, he wrote in his letter updating Senate Judiciary Committee Ranking Member Chuck Grassley that 24.4 percent of the applications submitted had received such changes. In addition, FISC judges seem to be tailoring their rulings to be better-suited for redaction and publication and address issues debated in the public; the court updates its website when it releases those documents.

But none of that reporting is mandated by FISA, and members are understandably hesitant to rely upon these ad hoc disclosures from the FISC. So they’re floating several proposals that would codify additional reporting requirements. Some bills read like a bulleted list of statistics the FISC must report regularly, while others are more deferential to FISC judges’ judgment. The difference between these proposals is striking: the Senate intelligence committee proposal focuses solely on mandating numerical reporting for particular types of surveillance programs and prefers deference when it comes to reporting significant legal interpretations. But other proposals address disclosure across the board, including aggregate data and the FISC’s legal interpretations of FISA. Importantly, Feinstein-Chambliss envisions a role for the Privacy and Civil Liberties Board in this area, unlike other proposals.

Data Reporting

Democratic Senator Al Franken, along with many from the Blumenthal-Wyden-Udall group, would mandate a much more comprehensive annual report to Congress, one which would be available to the public, and allow providers voluntarily to disclose information to the public regarding data turned over to the government.

The Leahy-Sensenbrenner proposal would build upon the Franken bill to require Inspector General audits of Section 215 collection programs, national security letters, and of collection authorities outside of the country directed at non-US persons. It would also eliminate the one-year waiting period imposed on providers before they can challenge non-disclosures requirement that often accompany government orders for records in various national security contexts.

For FISA compliance and national security letters, the Leahy-Sensenbrenner would also require that disclosures by electronic services providers and congressional report data be rounded to the nearest 100. The Leahy-Sensenbrenner proposal would require an annual report to Congress that recaps the execution of FISA authorities and the impact of FISA on the privacy of U.S. persons. It requires Inspector General reports from the DOJ and the intelligence community.

Feinstein-Chambliss, by contrast, would wipe FISA basically clean of the piecemeal oversight and disclosure provisions and start over. Those regarding electronic surveillance, physical searches, and pen register/trap and trace devices would be organized into a single section. The bill would replace the various provisions with a semiannual report to “the appropriate committees of Congress” (the intelligence and judiciary committees) that must include, for each of the foregoing FISA activities, the total number of applications submitted, granted, denied and modified; the number of non-emergency circumstances proposed and final applications; the number of named U.S. persons targeted; the number of emergency authorizations; and the number of new compliance incidents. Under the legislation, an annual report to the public would include this information, too. That public report may include more details, though these could be withheld as needed in order to protect national security secrets. As to business records and Section 702 collection, Feinstein-Chambliss would require the AG to make the existing reports available to all members of Congress, and would mandate a public report, again subject to protection of classified information.

Court Records

A final issue is the publication of court records in FISA cases. There’s a measure of consensus here, too.

Currently, Congress delegates to the Chief Justice of the United States the authority to adopt security measures for court records; the FISC has adopted rules of procedure to do so. Generally speaking, the Clerk of the FISC is not permitted to release any court records; FISC Rules of Procedure Rule 62, however, permits a judge—sua sponte, or on a party’s motion—to order an opinion, order or decision be released. The Presiding Judge is permitted, but not required, to direct the Executive Branch to then review the order, redact it as necessary, and publish it. And while it’s clear that the FISC has been more deliberate in declassifying its opinions (and making them more readily declassifiable, as noted above), the statute doesn’t impose any requirements on the AG or the court to selectively publish FISC opinions—all the opinions that have been released, thus far, have been done in accordance with Rule 62.

The major proposals all involve some kind of enhanced disclosure of FISA court opinions. Leahy-Sensenbrenner, the bill proposed by Senators Merkley, Blumenthal, and Leahy, 10 other Democrats, and the GOP Senate trio Heller, Lee and Paul, and the Blumenthal Special Advocate bill would all require the AG to declassify and make available to the public FISC opinions consisting of a “significant construction or interpretation” of the business records provision that took place before the bill’s enactment (within 6 months) and in the future (within 45 days of submission). The AG would also have to release summaries of decisions not declassified, and an annual report discussing “internal deliberations and process regarding the declassification” process, including an estimate of the number of declassified opinions and those that remain classified. The Leahy-Sensenbrenner bill would incorporate many of the same provisions as Blumenthal’s bill, supplementing it with some additional provisions: additionally, the AG would also be required to publicly disclose decisions that are appealed to the FISCR, and would be required to “release as much information regarding the facts and analysis [in a decision] as is consistent with legitimate national security concerns.” The Special Advocate would also, in the new bill, have the authority to petition the FISA courts to publicly disclose materials, which the AG may oppose.

The Feinstein-Chambliss bill would require that the semiannual attorney general report include summaries of each compliance incident included in its count, and significant legal interpretations of FISA by the FISC and the FISCR, as well as the arguments made by parties before the courts on those issues. As to those decisions, the AG would also have to submit copies of court decisions records within 45 days of issuance of the decision. The reports would also have to be made available to every member of Congress. Feinstein-Chambliss, uniquely, would also incorporate reporting to the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board of applications involving “novel or significant interpretations of the law” that relate to counterterrorism efforts in a final application for an order for electronic surveillance, pen register/trap and trace, business records, acquisitions within the United States regarding a United States person located outside the United States, acquisitions targeting U.S. persons located outside the United States, a review of a procedure targeting non-U.S. persons located outside the United States, or a notice of non-compliance with a FISC order. In those instances, the PCLOB would receive the application on the day it is filed, and the resulting FISA court order when it is issued. The PCLOB then, would conduct an assessment of the application’s consideration of privacy and civil liberties concerns. The PCLOB would also conduct an annual review of NSA FISA activity.

Takeaway: the varied proposals start from the premise that more information about FISA activities, and the operations of the FISC, needs to be made available to Congress and the public. The differences go to the specific kinds of data made subject to regular reporting; and to what sorts of FISC opinions should be declassified and made available to the public.

This story was cross-posted at Lawfare.