American politics is a famously contentious theater, especially today. But the vast majority of liberals, conservatives, and Washington journalists all seem to agree that “extremism” is appalling and should be eradicated.

Yet, the meaning of the term is as prey to ideological dispute as are such holy words in our political lexicon as “freedom” and “rights.” Conservatives call Bill de Blasio, who is about to be elected mayor of the nation’s largest city a “left-wing extremist,” while liberals counter that anyone with ties to the Tea Party is an “extreme right-winger.” “Extremist” is the description of choice for fundamentalists of any religion; unless, of course, you belong to one of the faiths being gored. In that case, it’s only traditionalists from the other religions who are “extreme.” “Community,” the literary critic Raymond Williams once observed, “seems never to be used unfavorably.” But no one has a kind word to say for extremism or extremists.

Well, let me be the first. Sometimes, those who take an inflexible, radical position hasten a purpose that years later is widely hailed as legitimate and just. Extremism is the coin of conviction, whether virtuous or malign. It forces middle-roaders to crush the disrupter or adapt.

In the 1830s, the “moderate” way to abolish slavery in the U.S. was to compensate slave-owners and ship their former chattels, nearly all of whom were American-born, to Africa. Extreme abolitionists argued, loudly, that it was a sin to hold human beings in bondage; nothing but immediate freedom would do. “I am aware that many object to the severity of my language; but is there not cause for severity?,” asked William Lloyd Garrison. “I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or to speak, or write, with moderation.” A little over three decades later, his principles were written into the Constitution.

Over time, certain other extremists on the left also turned out to be prophets. Moderate authorities in politics and the media once lambasted such pioneer woman suffragists as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, militant opponents of Jim Crow like Ida Wells Barnett and W.E.B. DuBois, and early critics of the war in Vietnam like the members of Students for a Democratic Society and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. But who would now claim that only men should vote, the races should be segregated, and that it was a good idea to send more than a half a million soldiers to Indochina?

In fact, ideological movements probably need to be immoderate if they hope to grow. In 1964, two officials of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai Brith wrote a book to alert the public about “the current Extreme Right phenomenon.” Included among their targets were the Young Americans for Freedom and the founder and editor of National Review. “When it comes to deploring the extreme and dangerous condition of the United States and of all Western civilization,” cracked the authors, “you have to get up pretty early in the morning to outdo William F. Buckley, Jr., the aging Boy Wonder of the American Right and a leading light of unabashed reaction.” Later that year, they must have felt vindicated when Barry Goldwater, in accepting the Republican nomination for president, declared “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice! And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue!” That oft-quoted phrase helped Lyndon Johnson win over 60 percent of the vote.

However, the Goldwater campaign seeded the conservative movement that grew to unprecedented heights during the next two decades. By taking principled, rigid stands in opposition to the welfare state and the permissiveness of American culture, “extremists” on the right inspired thousands of activists of all ages and provided the GOP with what Phyllis Schlafly called “a choice” rather an “echo” of the New Deal order. In 1980, Ronald Reagan easily defeated Jimmy Carter with much the same rhetoric he had used to praise Goldwater 16 years earlier. You’re no longer an extremist when you win.

Of course, compromise is called for whenever political opponents agree on the essential merits of a program, like Social Security and Medicare today, yet disagree about how to keep it solvent. But while conservatives are careful not to advocate tearing down such pillars of the limited welfare state, many also describe Social Security as “a Ponzi scheme”—which reveals their true intentions. When dedicated partisans treat every issue as an opportunity for moral combat, effective governance becomes all but impossible.

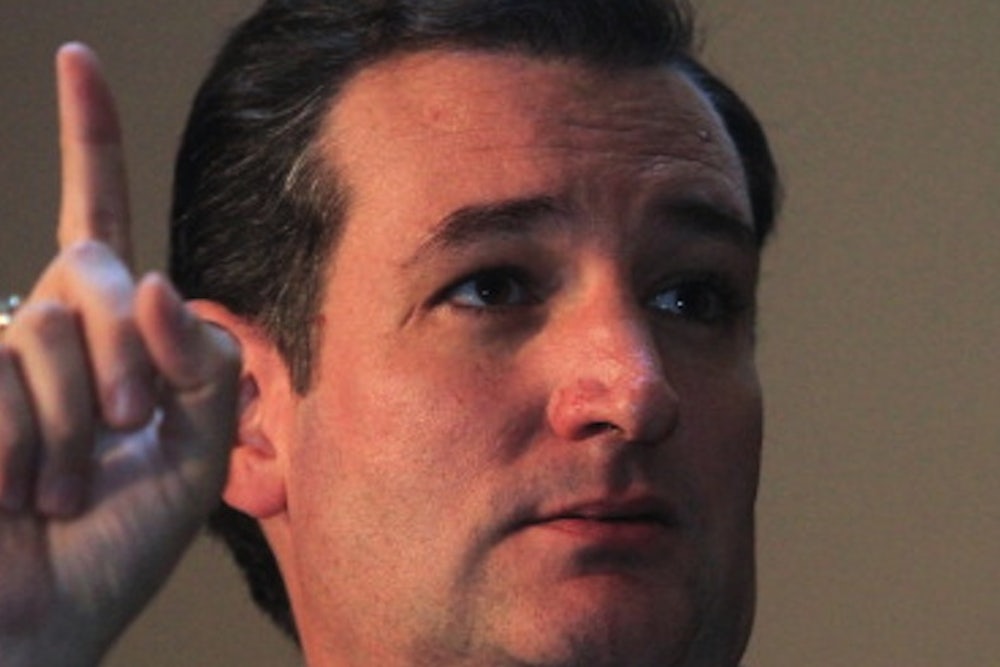

But to vaunt moderation over extremism just signals one’s good intentions without communicating anything meaningful about the issues at stake. If you think Bill de Blasio will bankrupt New York or Ted Cruz has no sympathy for the uninsured, then make that argument and drive it home with facts. Insisting that our biggest problems would be solved if everyone crowded into the middle of the road is a lazy attempt to avoid real debate about what divides us. It’s an extreme waste of time.

Michael Kazin’s most recent book is American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation. He teaches history at Georgetown University and is editor of Dissent.