At first glance, the event last week at the Lucky Strike restaurant-cum-bowling lanes at Gallery Place in Washington looked like most others on the city’s influence-industry circuit, with a table full of name tags for the expected senators, House members and staffers; young aides strapping wristbands on guests to designate them deserving of free drinks; and copious platters of chicken fingers and Asian rolls. But wait, what was this? This one also had big beige sacks labeled “Corn Meal” and “Corn Soy Blend Plus” propped here and there as decoration, and, on one of the video screens above the bar, incongruously bracketed by TVs carrying ESPN, a continuous loop of images of heavily armed, menacing-looking Somali pirates.

Meet the merchant-marine lobby, which not only exists but which is doing its utmost to capitalize on the confluence of two events: the negotiation this week of the much-delayed five-year farm bill, on which their members’ livelihood partly depends, and the success of the film Captain Phillips, which chronicles the exploits of a U.S. merchant mariner who was held hostage in a lifeboat after pirates seized his vessel, the Maersk Alabama, and attempted to hold it for ransom in 2009.

With a reporter’s fascination for little-known lobbies fighting for legislative fine print, I couldn’t resist an invitation to attend the event, a cocktail hour followed by a screening of the film at the adjoining cinema. Soon after arriving, I found my way to the relevant heavies, leaders of the International Organization of Masters, Mates and Pilots, a 5,600-member union that is based outside Baltimore and possesses what is surely one of the niftier names in the history of organized labor.

We exchanged some pleasantries but got quickly down to business, given the high stakes of the moment. The union recently triumphed on one front, mitigating, as part of the deal to reopen the government, the effect of budget sequestration on the Maritime Security Program, under which the government funds 60 ships in the 100-strong U.S. commercial fleet to carry military cargo around the globe. “What pirates couldn’t take away from Captain Phillips, Congress almost did take away through inaction,” said Captain Steven Werse, the union’s secretary-treasurer, who, like his compatriots, wore the union’s official anchor pin on his lapel.

But the union is now facing another threat: the push by the Obama administration and nonprofit groups to reform the U.S. food aid program so that more of the $1.5 billion Food for Peace budget is spent on food purchased in the host regions, rather than used to buy it from U.S. farmers. The argument for the new approach is that the money will go further at developing-world prices and without the cost of transoceanic delivery, and also that buying abroad will spur agriculture in the developing world. The main argument against it is that it cuts out American farms and the shipping industry, and thereby weakens already tenuous domestic support for foreign aid – a point the merchant marine union men were happy to drive home for me.

“The concept of paying people there versus paying people here is foreign to the American ethic,” said Werse. “We want American farmers to grow the crops…and American ships to deliver them. The concept of handing a check to a third party is ludicrous.” He pointed over at one of the big sacks, noting the big Stars and Stripes and “From the American People” stamped upon it. Would we really want to replace that with a mere check, with no visible reminder for the beneficiaries of its true source? “Food is a political tool, and we like to level that on a national level to show that we are a good people, that we care about the world,” he said.

Don Marcus, the union’s president, was blunter in his scorn for the reform proposal. First of all, it wouldn’t work: “Food often isn’t available locally, or people wouldn’t be starving!” Plus, “the money would be siphoned off by racketeers” and “end up in a Geneva bank account.” Then Marcus, too, brought it back home: “What’s wrong with secondary gains for American farmers or with providing a stream of cargo for the American merchant marine?” Losing the food aid task would imperil the entire merchant marine fleet on which the military depends for the Maritime Security Program, he said. “If you presume to be the world’s greatest military, you better have ships,” he said.

The union’s man in Washington, James Patti of the Maritime Institute for Research and Industrial Development, told me he was fairly confident that his side would prevail in the negotiations: While the Senate version of the farm bill calls for shifting a bit of the funding over to purchase-abroad, it doesn’t go nearly as far in that direction as the 45 percent share the administration was seeking to shift, and the House bill (which severely cuts domestic food stamps) preserves the status quo.

Still, Patti said, the industry needed to be hyper-vigilant, not least because there just isn’t the depth of public awareness of it that there used to be, now that most shipping is done by massive container vessels that come and go in sprawling harbors set away from city centers (case in point: a longshoremen’s strike recently shut down Baltimore’s huge port, of Season 2 of “The Wire” fame. Did anyone not happening to read about it in The Sun even know about it?) “It is a problem,” Patti said. “People don’t think about how [goods] are getting from here to there, and vice versa. They just miraculously appear. You buy it on QVC and a few days later it shows up.”

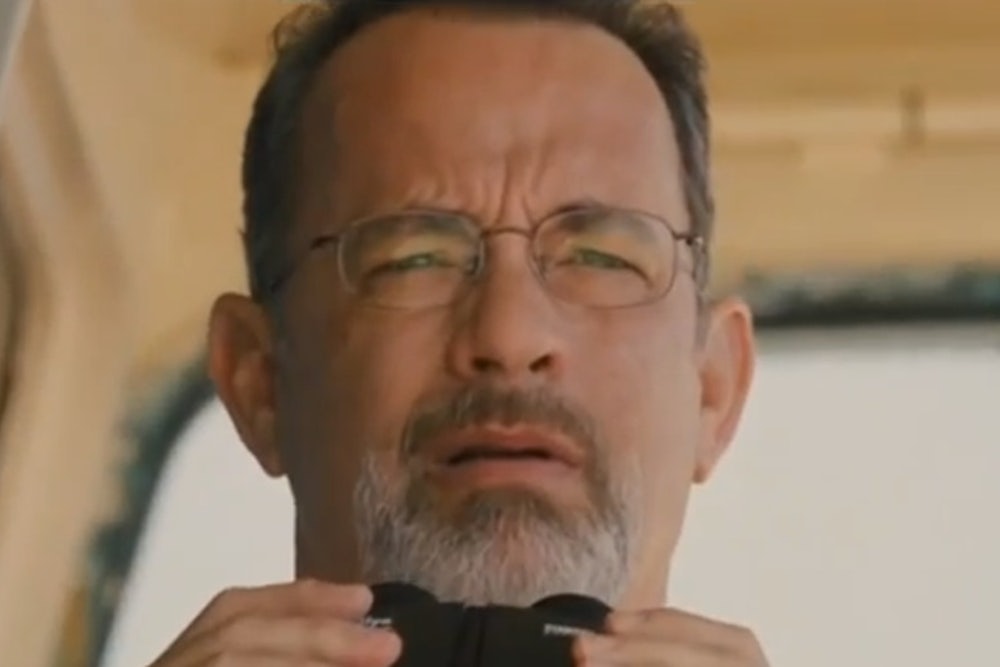

That’s where Capt. Richard Phillips comes in. The Paul Greengrass film is drawing crowds—it finished last week in second place, with $17 million in ticket sales—and reminding thousands who think of the high seas as the backdrop for cruise liners and aircraft carriers of the existence of this other universe. “It’s the 15 minutes of fame for the merchant marine,” said Marcus.

Tom Hanks, who plays the title role, was not at Lucky Strike, but the man himself was, looking pretty much as you’d expect a merchant mariner out on the town to look, with a Captain Haddock beard, serious brown loafers and a blue sport jacket and chinos. He seemed perfectly at ease, but professed to find the event and the general whirlwind of the film release “a little surreal.” “It’s not my normal routine,” he said. “Most of the time I’m working on ships.” Actually, the usual schedule is three months at sea and three months off—he just returned from a long circuit that included Belgium, Singapore, and Japan, and is now back at his country place in Vermont. What does he make of the political purposes to which his union is putting his stardom? “It’s good to reaffirm what we do,” he said. “We’ve been there since the start of the country and we’ll be there in times of need. We’re the truck drivers on the ocean.” What did he make of some of his crew members’ critiques of the film’s verisimilitude? “It’s a movie. Some of the schedule and order of things is off. But it portrays the stress of the situation.” And what does he make of Hanks’ portrayal? “He’s a regular guy, like me. He doesn’t take himself too seriously.”

With that, the captain was off to pose in more pictures. Among those crowding around him was Bob Livingston, the former Republican congressman from Louisiana who was an inch from becoming House Speaker when an adultery scandal derailed him, and who was at the event with his wife. Livingston is not lobbying on the Food for Peace debate, though a firm that his is allied with, Jones Walker, works on international shipping issues; Livingston was just there for kicks, he said. “My wife said to [Phillips], you’re much cuter than Tom Hanks,” he said. “I think he appreciated that.”

The room filled up as it got closer to showtime: among those in attendance were Reps. Renee Ellmers (R-N.C.), Alan Lowenthal (D-Calif.), and Mike McIntyre (D-N.C.), plus staffers for, among others, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-Va.), and senators Mark Warner (D-Va.) and Tim Scott (R-S.C.). As word went out that it was time to file into the cinema, a woman with a flag pin the size of a Luna moth sidled up to Clint Eisenhauer, vice president for government relations at Maersk, which was co-sponsoring the event. She was Rebecca Dye, a George W. Bush-appointed member of the Federal Maritime Commission, the agency overseeing Maersk and other shippers.

“Thank you very much,” the regulator said to the regulated. “This is very nice.”