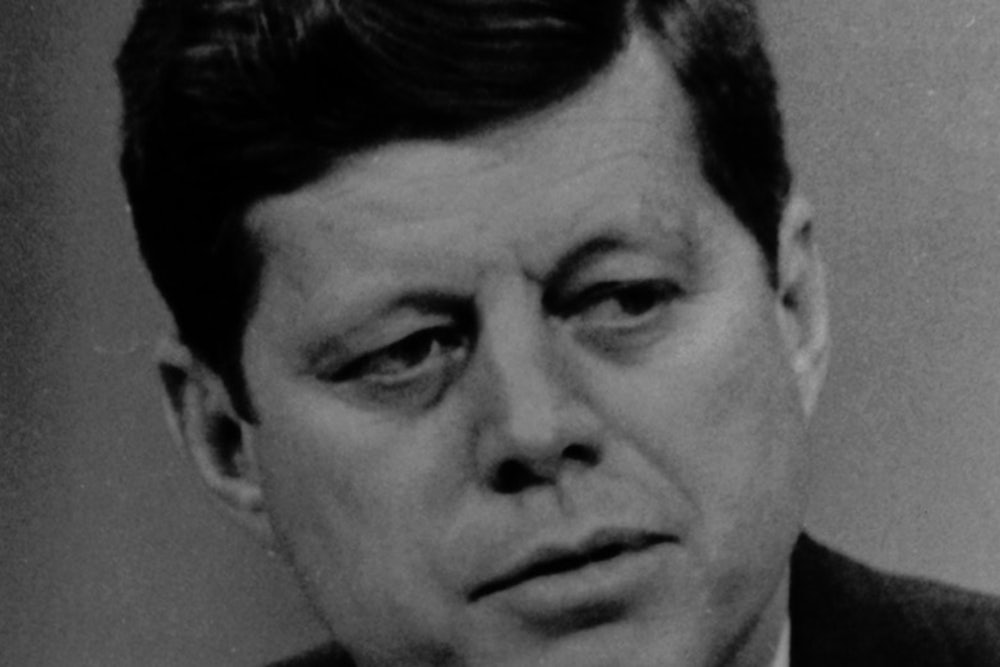

This is the 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, and both the New York Times and the Washington Post devoted their Sunday book sections to reviewing old and new books about what Jill Abramson called “the elusive president.” One of the books they do not mention is one of the most important ever written about him, The Search for JFK by Joan Blair and Clay Blair, Jr., which was published in 1976 and is out of print. I read it in the early ‘80s when I was trying to figure out how to write a biography. I am not an expert on Kennedy’s presidency, but I have read enough to say that what the Blairs wrote about Kennedy was earth-shaking at the time and has, as far I know, not been disproven or discredited. Yet, their work has been completely forgotten. On Nexis-Lexis, I could find no mention of the book during the last 20 years.

Clay Blair was a well-known military historian and the editor of the Saturday Evening Post, and his wife Joan Blair co-authored several of his books. They set out to write the story of Kennedy’s early years up to his becoming Senator in 1953. They became convinced that the standard biographies of Kennedy slighted or distorted these years, but they were stymied by the refusal of the Kennedy Library to release relevant documents. So they set about interviewing more than 150 people who had known Kennedy back then. The result is not a conventional biography, but a chronicle of their attempt to find answers for the questions they had about Kennedy’s upbringing, school life at Choate and Harvard, service in the Navy, and early political life as a congressman. They quote at length from letters they discovered, but also from interviews they conducted. If the subject were less fascinating than Kennedy, such an approach might be tedious, but I found the Blairs’ book to be riveting.

At the time, their most controversial finding was about Kennedy’s medical history, documents about which the library refused to disclose. What they were able to piece together was that Kennedy, who during his presidential campaign had declared himself “the healthiest candidate for president in the country,” had been sickly from his youth and had almost died from Addison’s disease, for which he had to be continually treated while he was president. “His health, almost from birth,” the Blairs wrote, “was disastrously poor.” He was born with an “unstable back,” which required two operations, he had to take a year off from college because of illness, he left the Navy because of poor health, and in 1947, he was diagnosed with Addison’s, which consists of a malfunctioning adrenal gland. If anything, these various ailments would converge during his presidency.

The Blairs also punctured other myths that Kennedy, his father Joe, and his supporters had created about the 35th president. According to the Blairs, Kennedy’s reputation as a “war hero” had been carefully constructed by his father through his contacts with Reader’s Digest. Kennedy’s PT-109 had been part of a of 15-boat flotilla that was supposed to intercept Japanese destroyers. When the destroyers appeared, Kennedy failed to attack, as he had been ordered. During a second engagement, Kennedy did speed toward the destroyers, but failed to alert his crewmen and was rammed by a destroyer. Kennedy did save one of the crewman, but others were killed.

Little was known at the time the Blairs wrote about Kennedy’s sexual escapades in the White House, but in recounting Kennedy’s various affairs, the Blairs anticipated these revelations. “He enjoyed foremost the manly companionship of male friends,” they wrote. “Women were secondary and primarily sex objects. He relished the chase, the conquest, the testing of himself, the challenge of numbers and quality… Jack appeared to avoid women who were ‘eligible’ (acceptable to family and Church) for marriage. Like his father and Joe Junior, he was drawn to beautiful models or starlets in café society.”

Finally, the Blairs cast doubt upon Kennedy’s reputation, based on his Harvard honors degree, study in London, and his authorship of Profiles of Courage, as being a scholar and intellectual as well as a politician. He had, the Blairs acknowledged, a “curious, inquiring mind” and was “well-informed” about international affairs, politics, and English history, but he was a mediocre student at Choate and Harvard, and never actually attended the London School of Economics. The one exception was his honor’s thesis at Harvard, which earned him a cum laude degree, and which was published as Why England Slept. But the Blairs discovered that the thesis, which was not highly regarded by Kennedy’s advisors at Harvard, was prepared for publication by the New York Times’ Arthur Krock, who was part of Joe Kennedy’s circle, and, according to later accounts, may have been on retainer. (Kennedy’s authorship of Profiles in Courage, which has also been questioned, comes after the Blairs’ book concludes.)

Have the Blairs’ claims about Kennedy held up? In 1992, in the Journal of the American Medical Association, two pathologists who worked on Kennedy’s autopsy disclosed that he had suffered for many years from Addison’s disease. Then in 2002, historian Robert Dallek wrote in the Atlantic Monthly of “The Medical Ordeals of JFK.” Dallek had been given access to Kennedy’s medical records and what he found confirmed what the Blairs had written. The records reveal, Dallek wrote, “a story of lifelong suffering.” During times of stress in his presidency, Kennedy was taking “an extraordinary variety of medications: steroids for his Addison’s disease; painkillers for his back; anti-spasmodics for his colitis; antibiotics for urinary-tract infections; antihistamines for allergies; and, on at least one occasion, an anti-psychotic (though only for two days) for a severe mood change that Jackie Kennedy believed had been brought on by the antihistamines.”

While Lawrence Altman, the New York Times health reporter, acknowledged the Blairs’ groundbreaking research in a 1993 article about the Kennedy autopsy findings, Dallek does not mention the Blairs in his article. He writes that “the lifelong health problems of John F. Kennedy constitute one of the best-kept secrets of recent U.S. history.” In his biography of Kennedy, An Unfinished Life, which Abramson says is “the best of the full biographies,” Dallek does cite the Blairs’ book in his footnotes, and he does also acknowledge in his text that the Blairs’ account of the battle in which Kennedy’s PT-109 was engaged was “authoritative.” The Blairs’ other findings about Kennedy’s affairs and his scholarly pretensions have become standard biographical fare.

What happened to the Blairs’ book? Why has it disappeared? It’s not because it’s old. In Abramson’s sample of JFK writings, four of the seven books or articles she cites were written before 1976. The matters the Blairs wrote about didn’t bear directly on Kennedy’s policies as president; interest in Kennedy has always gone well beyond what he actually did as president. I suspect it has to do with Clay Blair being an editor of a popular magazine rather than a historian or journalist. And it may have to do with the peculiar nature of the Blairs’ book. They really don’t reach any conclusion about Kennedy’s presidency or even about Kennedy’s character except the very important one that the image he projected—and that was carefully nurtured by his father and various camp followers—didn’t necessarily correspond to the man’s reality.

The Blairs’ book also suffers from the fact that many of their findings—although controversial at the time—have now become widely accepted. That’s probably a good reason not to list the Blairs’ book among those people should read now to learn about Kennedy. But I have to say that in reading the Blairs’ book, I not only learned a lot about John Kennedy, but I also learned how to research a biography. The lessons went something like this: Don’t rely on secondary sources; question everything about a person’s history, even, say, their peculiar accent or odd habit; and when you don’t find answers, look for people who knew him back then (if he is alive or recently deceased) and for clues in nooks and crannies, like school yearbooks or letters to the editor of small-town newspapers. Aspiring investigative journalists could also do worse than to read the Blairs’ book. It’s a guide of how to find out things the authorities don’t want you to know.