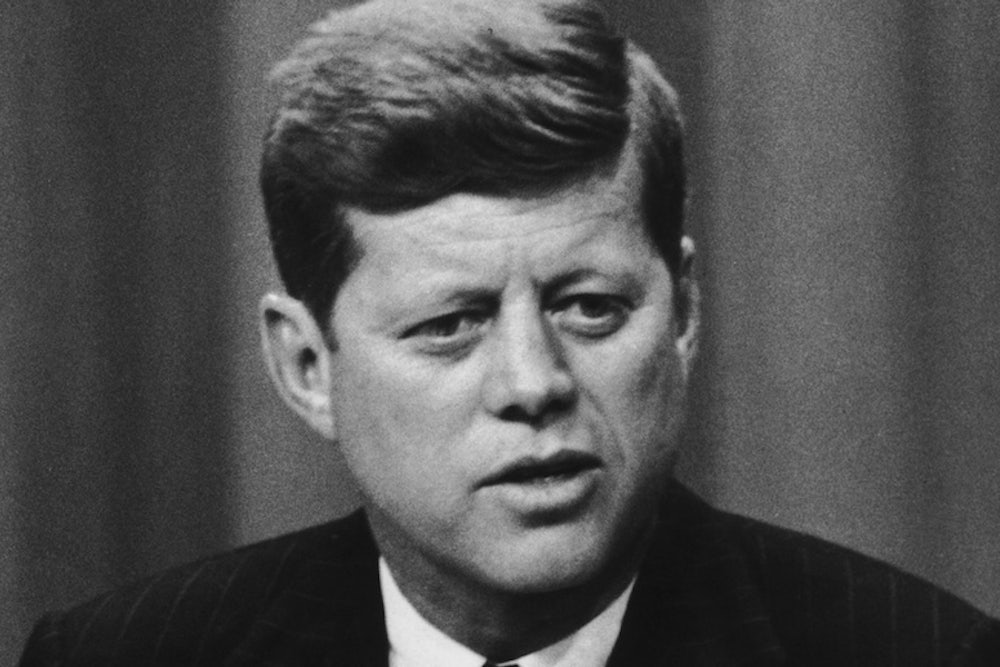

"JFK's Television Presidency," by Henry Fairlie

The New Republic, December 26, 1983

To read more of The New Republic's coverage of the Kennedy Assassination, click here.

Did John F. Kennedy exist? The question is not facile. It is the natural response of anyone who followed the nation's month-long observance of the twentieth anniversary of his assassination. From the scores of network and local television programs, from the millions of words that appeared in newspapers and magazines, from the books pasted together for the occasion, we ought to have been able to learn more of the man and the politician, of the achievements of his Administration, and perhaps above all, more of the meaning of the legend of Camelot to the American people now. With very few exceptions, we learned nothing at all. And what we did learn was that Kennedy has not yet been placed in the American mind: That the legend of Camelot has faded, and the reality of those years has not yet been grasped.

USA Today opened what Adam Walinsky called the "media extravaganza" on November 1. Its "cover story" carried the headline, "JFK: A Month of Memories Begins," with a predictable color photograph of the young Caroline Kennedy leaning on her father's shoulder. From then until November 23 the floodgates were open. It is not curmudgeonly to ask why so much attention was paid to this anniversary. Franklin D. Roosevelt was a far more important president. But go back to the newspapers for April 1965: They passed over his death twenty years before. None of my researches has discovered any brooding in 1921 over the assassination of William McKinley, although the fact that he was shot in 1901 by an anarchist ought surely to have invited many conspiracy theories. (But then one must again acknowledge the influence of television. It is unlikely that the television series "Dallas," a drama of violence and intrigue, would have been given such a setting without the assassination; one cannot imagine a similar television series called "Buffalo," where McKinley met his death.) A university librarian has assured me from his own investigations that in 1885 little was written to recall the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Why were Kennedy's life and death so celebrated?

One thing can be said abruptly. The fact that Kennedy was assassinated is less significant in the memory of the nation—there have been Presidential assassinations before—than that the assassination at once became and has remained a television drama. This crucial importance of television struck me even as the weeks of remembrance passed. I was invited to a preview of ABC's two-hour documentary, "JFK." After about thirty minutes during which I wondered what was surprising me, I whispered to my neighbors, including one of the senior producers of the program, "It's all in black and white. I had forgotten how new television was then." The black and white was accentuated by two other factors: every now and then the anchorman Peter Jennings popped up on the screen in living color; and the pictures of J.F.K. and his time were shot in film, not videotape. Film on television has a slightly fuzzy, nostalgic, even appealing look, rather like an early Buster Keaton short. But the black and white had made the point. Kennedy was the first television President.

As the days of celebration and appraisal passed, this was demonstrated most vividly not only by the various television programs on J.F.K., but by the television critics in the newspapers, especially by Tom Shales, the very able TV reviewer for The Washington Post. He was a young man on November 22, 1963, "working for a small radio station in the Midwest," as he told his readers, when "the U.P.I, teletype machine sounded five bells, which meant bulletin, and I watched as it noisily spat out the unthinkable." Shales is usually very levelheaded about television. In reviewing the Kennedy programs he went off his head. Why?

Everyone I know thought that the ABC documentary was a realistic appraisal of Kennedy's record and, given the thinness of that record, it nonetheless made every effort to award him the honor due to him. This was not enough for Shales. “Tarnish in Camelot” was the headline for his review. He found the program "an unseemly slur on the Kennedy memory," an "unsavory enterprise" of "studied irreverence." Had Shales seen the same program as I had? I turned it on at home that night for a second look. Although it was certainly critical of the Kennedy legend, it was not only instructive but dignified.

Shales wrote two more long articles on the television coverage, and in the second he revealed the reason for his prejudice against the ABC program. "Thumbsuckers that analyze Kennedy's effectiveness as chief executive or try to determine his place in history—like ABC's misbegotten 'JFK'—are boring. Attempts to recapture through television the feel, not the facts, of the times, and the elusive incandescence of the Kennedy persona are more intriguing." That might be the text for the whole month of remembrance. What the television critic wanted was the Presidential television image. The feel—the persona—not the facts. He quoted Kennedy as saying of his Administration, "We couldn't survive without TV"; and he even remarked that "No President came close to Kennedy as a television presence until Ronald Reagan." Again the phrasing is telling. The television presence of a President. That was what Shales wanted, and, by and large—his complaints notwithstanding—that was what we got for a month, even in print. And we got it because that is exactly how Kennedy used television at the time. "On television in 1960," wrote John Corry, the television critic of The New York Times, "Mr. Kennedy was a picture of grace," and he noted that "television news coverage expanded during the Kennedy Administration, and in large part Mr. Kennedy inspired the expansion."

In Shales's third article he rightly demolished the NBC mini-series, "Kennedy," memorably calling it "the latest delivery of toxic waste from NBC." The program was indeed "trashy . . . tawdry . . . cheap pulp." Much like Garry Wills's book, The Kennedy Imprisonment, published a couple of years ago, and Ralph Martin's new book, A Hero For Our Times, it played fast and loose with unsupported rumors, with keyhole gossip and bedroom tales; and as the books should not have been written, so should the mini-series not have been made, and not been shown. (I like to think that in The Kennedy Promise ten years ago I showed that it is possible to criticize Kennedy and his methods severely without denying that he was a man not only of honor but of public dignity in his office, a quality which we have sorely missed since then.) But it is worth remembering about Shales both that he is a television critic, reviewing television programs about a television Presidency, and that he is of the generation which took most of its image of Kennedy from television. When he writes of "a slain and fondly remembered President and his wife," and speaks of the NBC mini-series as "like part of a plot to take whatever remaining heroes we have away from us," he is writing from the bright promise of his own youth.

Thanks to PBS, which broadcast highlights from J.F.K.'s celebrated news conferences at the same time as the final episode of "Kennedy," one could switch from the travesty to the reality: to the reality, at any rate, of the image which Kennedy was able to project on television. It was impossible not to be attracted again by the appearance of the man, to enjoy the nimbleness of the wit, the charm of his gaiety, and even to reflect that, for all the lengthy briefings with which he was prepared for these appearances, he displayed on his feet an intelligence which was wholly individual, and had to invite from all but the most skeptical a measure of trust and reassurance. The criticisms which I made in 1973 of his use of these occasions still stand. He was not only cunningly evasive, but often devious, and he sometimes blatantly lied, not least over the United States's involvement in Vietnam. But today I would shift more of my criticism against the press than against him. If J.F.K. had a love affair with television—and how could so youthful and vigorous a man not seize the opportunities it offered?—the American press just as certainly had a love affair with him. Some journalists of that time were honest enough to admit this in the past month.

Bearing in mind the amiability with which Reagan is now treated by most of the White House press correspondents, it needs to be said that even print journalists enjoy covering a television President. The more and better he uses television, the more stories about the President are demanded. As one could sense all through the Kennedy press conferences, reporters were delighted to be part of such a class performance. They were eager to play the straight men to so winning a leading actor. There was a willing suspension of disbelief.

The Presidential television presence is at the core of the question of "style" versus "substance" around which any debate about Kennedy revolves. It was raised again and again in the appraisals of the past month, but generally to be evaded or at best obscured. Perhaps most tellingly, it was most often evaded by talking of the "promise." In an editorial on November 22, The Washington Post conjured with the word:

"A whole class of people, many of them of the generation whose fondest promise he was held to embody. . . . That John Kennedy had great promise is indisputable. . . . True, there is a less flattering way to put it: much of his vaunted promise arose from the fact that he died before he was called upon to make full delivery. . . . We are, however, a nation that prides itself on its promise."

The word "promise" here slides from association to association until it is robbed of all meaning. What indeed was "the fondest promise" of the generation which he seemed to embody? It could have been anything from the promise of strength and adventure (the almost martial tone of the Inaugural Address) to the promise of negotiation and peace (the much-quoted speech in 1963 at American University in Washington).

But clearly people were not talking of the promises he made, much like any politician, and contrasting them with his actual performance. If that were the case, there would be little to be said. He might, in the end, have delivered, if he had lived. We can never know. Instead, the "promise" was represented in "the legacy" which he was said to "embody," all terms which seem popular for their haziness, and which people apparently found hard to avoid. Strip to the bone most of what was written and said, and all that was really meant by the word "promise" was that Kennedy raised a people's expectations of what could be achieved through politics.

My task here is not to try to define these intangible hopes but to understand how they were raised. And this returns us to the phenomenon of the television President. On the screen the impact of the man and his family and his circle was direct and immediate and so far unrivaled. He was the first politician in any nation to realize that television had given politics a new arena. He did not teach the activists and militants and demonstrators with whom we are now familiar that they must play to the cameras. But he was the first to demonstrate beyond dispute that there was a new stage. As even the mobs outside the American Embassy in Tehran knew four years ago, television is a medium, which can be commanded to put on any show with a spice of drama. I stick to my criticism of ten years ago that, by raising the expectations of politics to such height, Kennedy agitated the political atmosphere, overdramatized what actually goes on in the political arena, and contributed to the disillusionment which followed when the expectations were not fulfilled. But the essential point is that he managed it through television, and one of the few new illuminations provided by the month of remembrance was that television is viewed differently by different generations, and the "promise" or "legacy" or "legend" of Kennedy is viewed differently by them as well. The generations, separated now by little more than a decade, have much different responses to Kennedy than to any other president.

To those who were old enough, the television memories are ineradicable, even their memories of the assassination. The assassination was thus a wholly fitting climax to a television drama. That was where most people saw the assassination: the long motorcade, the smiling President and the waving First Lady, the rush to the hospital, the return flight on Air Force One, the funeral. But those too young to have these memories have grown up with television. They do not quite believe anything they see on it. No audience of students has ever applauded me more uproariously than when, from my own experience of doing television documentaries in Britain, I remarked to a few hundred of them: "If it was on television, it didn't happen." In the past month I could sense from many of those of high school or college age today that they did not really believe the Kennedy story even as they watched it on the screen. It is not their cynicism; not a cult of the antihero. "He glittered when he lived," Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote a few weeks ago in The New Republic. If he did, he glittered most on television. But no president is going to glitter on television to a generation that was first propped in front of the box at the age of three months.

I would even suggest that a television presidency will be automatically distrusted by them. But this only returns us to the question of what the television presidency signifies, of what is telling in the fact that Kennedy was the first president fully to exploit the new medium. Tom Shales makes the leap from Kennedy to Reagan as two television presidents:

"Kennedy's was an Administration that was also a TV series; Reagan's often seems a TV series that is also an Administration. Kennedy thrived in a situation that exploited his quick wit and charm; Reagan, slower of wit, prefers choreographed press conferences. Kennedy was heavily briefed; Reagan is heavily coached. Kennedy took to television more or less instinctively, and it showed; Reagan is an actor."

He goes on to make the point that both of them "owe something of their political fortunes" to their performances in television debates against opponents who were much more "maladroit at utilizing the medium." This is all just. But the television presidency is much more than a matter of the televised debates and press conferences and addresses which a president can give. Television has altered the entire nature of presidential campaigns—even dictating the character and timing of the events which are held to be crucial—and has also altered the character of presidential leadership. The extraordinary impact on public opinion of Reagan's defense of the Grenada invasion is not an encouraging omen. Yet this is exactly how Kennedy used television. It is a medium which magnifies the already considerable opportunities for a president to appeal over the heads of Congress directly to the people. This was my central criticism of the Kennedy method. He liked to bypass the political process—Congress and the bureaucracy—by reaching to the public directly. What needs to be asked after observing the reactions of the different generations to the celebration of Kennedy's life and presidency is: what happens now, when a generation that disbelieves what it sees on television and so will automatically disbelieve a television President, is about to enter the political arena?

Did John F. Kennedy exist? No young person watching television last month seemed quite convinced. That was perhaps the most provocative revelation of all. This generation has lived under no President who has shown any sign of growth in office. During its lifetime the American electorate and the American political system have not performed well in the selection of Presidents. Why should young people believe or hope? And if we look for the main reason why the political process has performed so poorly, the answer will again be found in the very medium which they by nature disbelieve. They see their Presidents chosen by and their country governed through television. They have seen the world through television since they were tots, and seen through all its ruses, and that is why the Kennedy legend does not persuade them.