The New York Times story earlier this week on how “Senate Women Lead in Effort to Find Accord,” about a group of five women senators, left a bad taste in my mouth. The central quote, from which the article derived much of its persuasive force, came from Sen. Susan Collins: “Although we span the ideological spectrum, we are used to working together in a collaborative way.” But that analysis relied on a gender stereotype (albeit a positive one) and a willful blindness to other things that may have driven these women together—such as the fact that they actually don’t span the ideological spectrum as much as a random grouping of bipartisan senators would (Collins, Kelly Ayotte, and Lisa Murkowski are moderate Republicans from New England and Alaska, while Barbara Mikulski and Patty Murray are veteran, pragmatic Democrats).

Most of all, though, the article rubbed me the wrong way because it defied what I know to be true, which is that the Senate is literally an old boys’ club—its 20 women members are the highest proportion it has ever had—and it did not persuasively explain how this exception could have arose, or even acknowledge that it was an exception.

Now, according to a new, retrospective tick-tock of the shutdown in Politico—a fantastic piece of reporting and storytelling, by the way—we learn that the deal the female Gang of Five was trying to cobble together is not the one that ended the standoff. The authors write:

Even though Collins was picking up support, she never had the full buy-in of party leaders from either side.

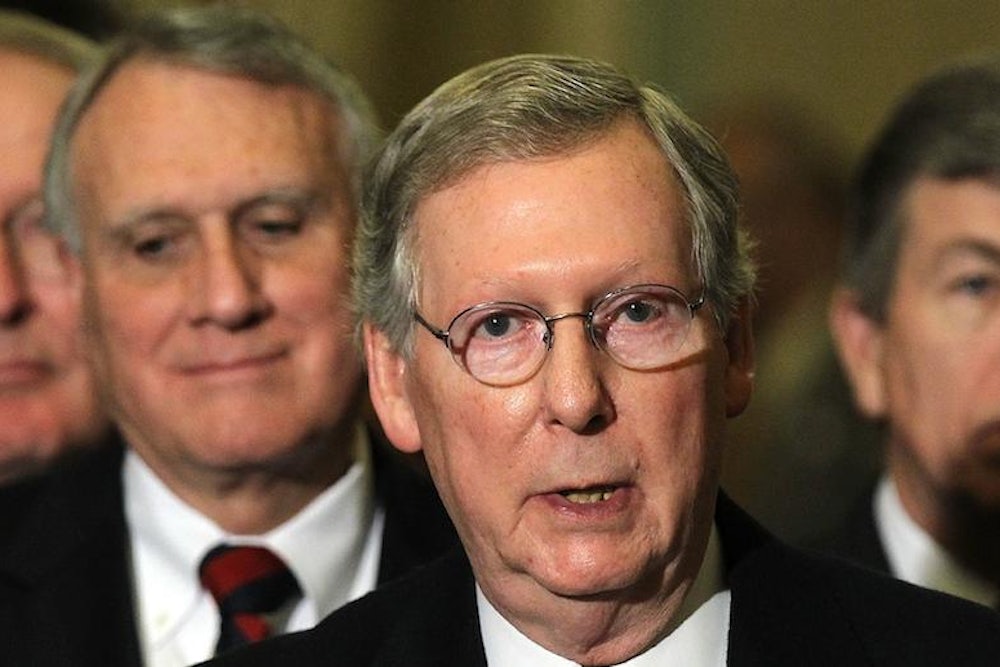

It was a veteran Republican senator, Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, who McConnell instead leaned on closely for some critical advice. Several sources said that Collins was upset when she learned Alexander was given this role, given that she had been working aggressively to cut a deal. McConnell aides later said Collins was critical to the end-result and nothing was meant as a slight against her.

But Alexander was important because his politics are more conservative than Collins’ and he has a tight relationship with Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), Reid’s closest ally.

This is a pretty perfect microcosm of the way old boys’ clubs work. I totally believe that cutting Collins out was not “meant as a slight against her.” But she lacks the standing necessary for senators to worry about slights against her. Meanwhile, all the important players here are friends or allies: Alexander, a previous chairman of the Republican Senate Conference, is close to McConnell, the minority leader; Alexander is also close to Schumer, the third-ranking Democrat; Schumer, in turn, is close to Sen. Harry Reid, the majority leader. Here is betting that these senators’ shared manhood is, at the very least, not an impediment to their “tight relationships.” And all of this is to be expected when 11 of the top 12 Senate officials are men and indeed when (paging 100 Percent Men) there has never been a woman Senate majority or minority leader or whip.

Seen in this light, the earlier Times article is worse than wrong—it’s actively counterproductive. Telling ourselves myths about female collaboration in the Senate enables us to overlook the actual continued male domination of the country’s upper legislative house. We are congratulating five senators who happen to be women for trying to be sensible instead of wondering why there aren’t more women senators (or more sensible senators).

Ironically, the Politico article does reveal an instance of two women senators exercising significant power during the recent to-do:

[The White House and Democratic leaders] could not accept the terms of Collins’ offer to extend government financing at lower levels through 2014. Patty Murray of Washington and Barbara Mikulski of Maryland, two powerful Democratic chairmen, refused to consider it.

That sounds awesome. Not too “collaborative,” though.