Mitch McConnell, leader of the Senate Republicans, approached Democrats with a new offer over the weekend: He and his colleagues would vote to open the government and increase its borrowing authority, as long as Democrats would agree to accept the depleted spending levels of budget sequestration. Harry Reid, leader of the Senate Democrats, said no thanks. It was the third time in less than a week Democrats had spurned a Republican overture. Previously, President Obama had rejected an offer from House Republicans and Reid had rejected a scheme being crafted by Maine Senator Susan Collins.

Now, even those Republicans who have been critical of their own party think the Democrats are being unreasonable. “You can blame us [Republicans], we’ve overplayed our hand, that’s for damn sure,” said Lindsey Graham, the senator from South Carolina. “But their response, where the president and [Reid] basically shutting everybody out, and when you try to negotiate, they keep changing the terms of the deal … it’s very frustrating.”

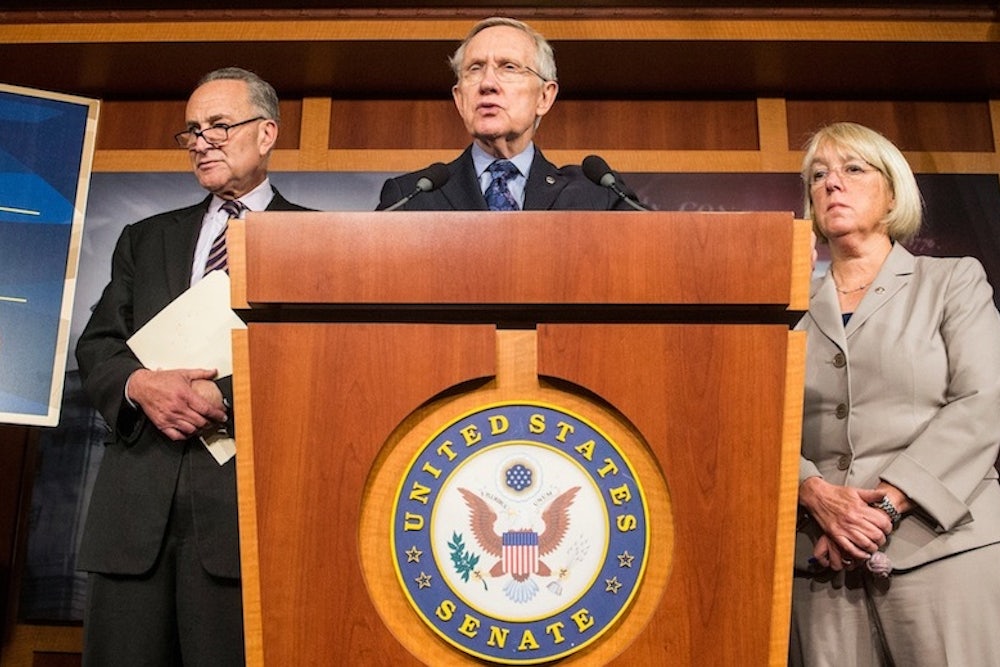

But Democratic leaders haven’t been changing the terms of the deal. On the contrary, Obama, Reid, and House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi have been remarkably consistent—over time and with one another. The Democrats are happy to negotiate over fiscal policy, they say. But they won’t allow Republicans to gain extra leverage by refusing to fund the government or increase the Treasury’s borrowing authority. As far as the Democrats are concerned, those tactics amount to extortion. Allowing Republicans to succeed, they say, would be even worse than shuttering the government or allowing a default—even though the former has been plenty bad and the latter would be even worse.

This doesn’t mean negotiations have ended. On the contrary, Reid and McConnell are still talking. Those talks will probably be the basis of whatever agreement ends this crisis. But Democrats have established a pretty simple test for new proposals: Is it a deal Democrats would make in normal circumstances, without a shutdown and without the threat of default? So far, nothing Republicans have suggested comes close to meeting that criteria.

Consider the three big proposals to become public so far. First House Republicans were asking Democrats to agree to negotiations that would lead to entitlement cuts. Then Collins imagined Democrats approving modest Obamacare changes, including a delay in the medical device tax. She also imagined domestic spending remaining, more or less, at the depleted levels of budget sequestration for six months. That was the same thing McConnell offered this weekend, although he thought it should be for a year.

The precise terms of these proposals are still a little fuzzy. It depends on who you ask and which media accounts you trust, in part (I’m guessing) because even the people thinking up these deals hadn’t fully fleshed out the specific principles. But in no case did Republicans imagine making policy concessions of their own. Rather, they saw Democratic concessions—cuts to Social Security or Medicare, Obamacare changes, lower domestic spending—as the price for ending the shutdown and avoiding the default. That made it precisely the sort of ransom that Obama, Reid, and Pelosi have said they will not pay.

Of course, Democrats still have a long list of things they want—among other things, an ambitious infrastructure program, money for the president’s pre-kindergarten initiative, and new revenue. In exchange for some or all of these goals, Democrats could in theory make concessions on their own—including, perhaps, the “chained CPI” proposal, which is basically a Social Security cut, or new taxes and fees on high-income Medicare beneficiaries, which is a way to introduce greater means-testing to the program. They could also live with sparing the Pentagon some of its sequestration cuts or some kind of reduction or delay in the device tax.

A negotiation about at least some of these issues is pretty much inevitable, since both Democrats and Republicans have been eager to alter sequestration before its automatic spending cuts take place in Janaury. Democrats want to address sequestration for the sake of sparing domestic programs, while Republicans want to spare defense. (For a detailed explanation of how sequestration politics play into current negotaitions, read the Huffington Post's Sam Stein, whose coverage of sequestration cuts has drawn national attention to the issue.)

But Democratic aides I interviewed over the weekend kept stressing one thing: Democrats won’t make a swap that doesn’t make sense on its own terms. In a normal negotiation, for example, Democrats wouldn’t trade sequester relief for chained CPI. That's why they wouldn't make that trade now, just to end the current impasse.

Republicans have heard this before. Many hoped it was just a bluff. So far, at least, it hasn't been.