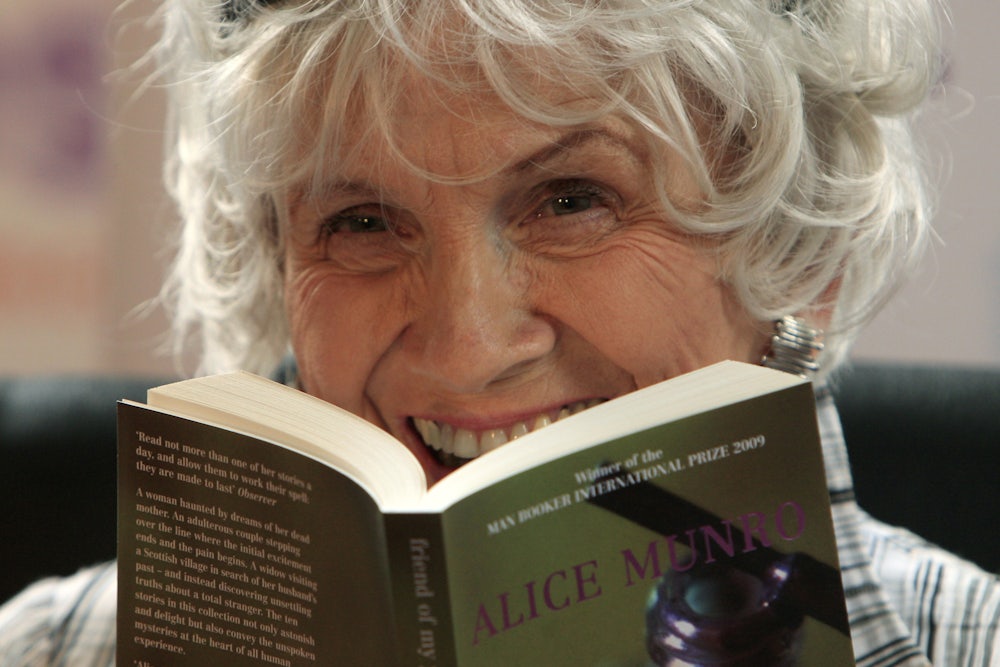

She had already won every other big prize, from the Booker’s newish international edition to the two big Canadian gongs, the Giller and the Governor-General’s Award. Yet it was still an unexpected delight when the Swedish Academy named Alice Munro, the “master of the contemporary short story,” as the newest laureate of the Nobel Prize for Literature. With the possible exception of Mario Vargas Llosa, she is the most popular writer to get the Nobel in a decade—and I’d wrongly suspected that her achievement was too placid to get the jury’s attention. I don’t count myself at all among the embittered anti-modernists, mostly Americans, who disdain the difficult writing that the Swedes have decorated in recent years (Elfriede Jelinek, abhorred by the American literary establishment, is a favorite of mine). But there are many different ways to be modern, and Munro should be counted, no less than the spikier winners of recent years, as a modern master.

In a 2003 interview with the Guardian, Munro observed, “I really grew up in the nineteenth century…. The ways lives were lived, their values, were very nineteenth century and things hadn’t changed for a long time. So there was a kind of stability, and something about that life that a writer could grasp pretty easily.” In a way, actually, you could fool yourself into seeing today’s prize as a throwback to an earlier Nobel tradition, when the Swedish Academy garlanded forgotten authors like Selma Lagerlöf of Sweden or Henrik Pontoppidan of Denmark–writers who found the stuff of literature in farmers and peasants at the turn of the century. My own suspicion, however, is that Munro will endure far longer than they did, even once the globe has warmed so catastrophically that Munro’s Ontario will have become a tropical paradise. Her significance comes not from her close observation of small lives in small towns, but from something much more modern: like William Faulkner, like Flannery O’Connor, she finds in those lives and fates enough material to shake the world.

How does she do it? Not the way you’d think. “Munro’s work is all about storytelling pleasure,” insisted Jonathan Franzen in 2004—a pronouncement that, like so many of Franzen’s, was both sweeping and wrong. Her stories eschew literary pyrotechnics, yes, but critics like Franzen, who harp about how Munro is an “enjoyable” or “accessible” author, do her a tremendous disservice. She’s not at all a breezy read; though the stories usually top out at 30 pages or so, they’re deceptively heavy and usually take more than one reading to parse. Nor is she the traditionalist that some of her fans might like her to be. The stories in fact exhibit deep formal innovation, making use of abrupt shifts in tone and bizarrely concatenated scenes that grind against each other like metal on metal. Hence the frequent sense of discomfort, even queasiness that a Munro story can leave you with. It’s not the failed love affair or the battle with cancer that stays with you—once you’ve read a lot of Munro, many of the individual scenes start to blend together—but a larger sensation of imbalance or precariousness. It’s as if the small dramas of rural Canadian life have upset the whole architecture of the universe. That sensation comes from form, not just plot, and it’s an eminently Nobel-worthy achievement.

Her stories are concentrated, slow-burning and almost embarrassingly Canadian: people go to “university,” not college, and sit on “chesterfields” rather than sofas or couches.1 (I first read Munro in a dingy basement of an apartment I was subletting in Montreal, stupidly convinced that I had to be in Canada to fully appreciate her.) Even if you’ve only read a few of her stories you probably have a feeling for the Munro terrain: southwestern Ontario, a flat, rural expanse of small towns and surging rivers. Her characters hover on the border between the working and middle classes, struggling with emotions and illness, small-town rivalries, dashed dreams, and the circumscription of “the lives of girls and women,” to borrow one collection’s title. Coming-of-age struggles are a leitmotif in Munro’s fiction. So are drownings: people are perpetually dying in those waterways, or in one gruesome instance in a gravel pit.

If there’s one theme Munro comes back to more than any other, though, it’s the deceptions of romantic love and its stubborn appeal in the face of heartbreak or treachery. Infidelity courses through her stories like the Ottawa river, from the stunning “The Spanish Lady” (in Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You), which begins with a woman reflecting on her husband’s affair with a schoolteacher, to “Corrie” (in the most recent collection, Dear Life), which depicts an adulterous romance between an architect and a younger, richer paramour. Why so much cheating? Perhaps because, in Munro’s Huron County, the promises of love never much convinced in the first place. In “The Beggar Maid”—first published in the 1978 collection Who Do You Think You Are?, then absorbed into a book of interlocking short stories titled The Beggar Maid, the character Rose fails utterly to understand how desire and reality mash up against each other:

She had always thought this would happen, that somebody would look at her and love her totally and helplessly. At the same time she had thought that nobody would, nobody would want her at all, and up until now nobody had. What made you wanted was nothing you did, it was something you had, and how could you ever tell whether you had it? She would look at herself in the glass and think: Wife, sweetheart. Those mild lovely words. How could they apply to her? It was a miracle; it was a mistake. It was what she had dreamed of; it was not what she wanted.

If you’ve never read Munro The Beggar Maid, published in 1978, is probably the place to start. From there you can head back to her earlier works, such as the lighter but still bracing Dance of the Happy Shades, or forward to the weightier, terser stories of the 1990s and the last decade, among them Open Secrets and The Love of a Good Woman. Of her most recent books, perhaps the most intriguing is the one that’s not really a short story collection at all: The View from Castle Rock, a disarmingly personal hybrid of fiction, memoir and history that takes as its starting point the author’s own genealogy.

It’s true that in the last fifteen years Munro achieved, in the English-speaking world, a position so unimpeachable that every collection and every new story was greeted with immediate hosannas (and, indeed, complaints that the Swedish Academy hadn’t recognized her greatness), which is not good for any writer. Christian Lorentzen, a perceptive if acerbic editor at the London Review of Books, observed earlier this year that “there’s something suspicious” about the manner in which nearly every profile or review of Munro begins “by asserting her goodness, her greatness, her majorness or her bestness.” It’s as if, Lorentzen put forward, Munro’s admirers know that her work is so lightly armed that they need to make a preemptive strike: insisting that her short stories are richer than most people’s novels, or that what looks like consistency in fact obscured tremendous variety. Reading all of Munro’s fiction in a row—not a good idea!—left him almost physically ill: “I saw everyone heading towards cancer, or a case of dementia that would rob them of the memories of the little adulteries they’d probably committed and must have spent their whole lives thinking about.”

Lorentzen took a lot of stick for that essay, not least from Canadians perturbed that their very own Chekhov had been torn to pieces by an American writer in a British publication. Yet he highlighted an important danger: if you don’t differentiate, and if you gorge on Munro as if she were just a storyteller, you’ll miss the forest for the Ontarian pines. Not only does such a binge obscure the variety in Munro’s oeuvre, such as the spiky Castle Rock histories and the excellent, often overlooked stories set in the 19th century. (Consider, say, “A Wilderness Station,” in the collection Open Secrets: an inventive and unexpected murder story told exclusively through fictionalized historical documents such as letters and newspaper clippings.) More than that, it reduces Munro to a series of incidents—affairs, illnesses, small-town jealousies—that really are small-bore. To get Munro, to see the innovation and the mastery that undergirds her achievement, you have to take your time. Don’t let the short length tempt you to fill up too fast; you wouldn’t gorge on Eliot, either.

One last point. A few months ago, accepting a Canadian award for Dear Life, her most recent collection, the 81-year-old Munro declared it was her last book and she was done with writing. It’s not the first time she’s tried to drop the mic—she pulled that trick in 2006 as well—but this recusal sounded more convincing than earlier ones, especially in light of that last book. Dear Life concludes with a suite of propulsive, disquieting stories that are preceded by a little paragraph, set in a sea of white and bearing the heading Finale. “The final four works in this book are not quite stories,” it reads. “They form a separate unit, one that is autobiographical in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact. I believe they are the first and last—and the closest—things I have to say about my own life.” What follows are some of the darkest and most powerful achievements of her entire career, especially “The Eye,” in which her own mother and the women of her Huron County imaginings are folded into one another. If they stand as her final words, that’d be as substantial a monument as any diploma from Stockholm.

- Munro is the first Canadian to win the Nobel – unless you count the Quebec-born Saul Bellow, which you shouldn’t. In a sleep-deprived interview with an airheaded Canadian Broadcasting Corporation anchor this morning, Munro’s vowels were notably northern: “I had forgotten all ab-ooot it.”