A three-day conference on cities in a fancy hotel a block from Ground Zero that concluded Tuesday was nothing if not well-timed. “CityLab,” co-sponsored by The Atlantic, The Aspen Institute, and Bloomberg Philanthropies, promised in its title to propose and highlight “Urban Solutions to Global Challenges.” Given that the current thing we instinctively look to in order to solve Global Challenges has been shut down for eight days and counting, New York City and cities generally seemed like a more-than-okay consolation prize.

But all is not well. “New York City is becoming unaffordable,” a mayoral candidate said. “And actually I see it happening throughout the country. The middle class is being squeezed. Certain costs are going up. Their base of pay is not going up anywhere near the cost of what it means to live in this city.”

This sounds, of course, like the Democratic nominee—and, almost certainly, next mayor—Bill de Blasio, who made “inequality” the central theme of his wildly successful campaign. Except it was not de Blasio who said the above. It was Republican nominee Joe Lhota, who elsewhere yesterday went after de Blasio harshly (and why not? Lhota’s down 50 points).

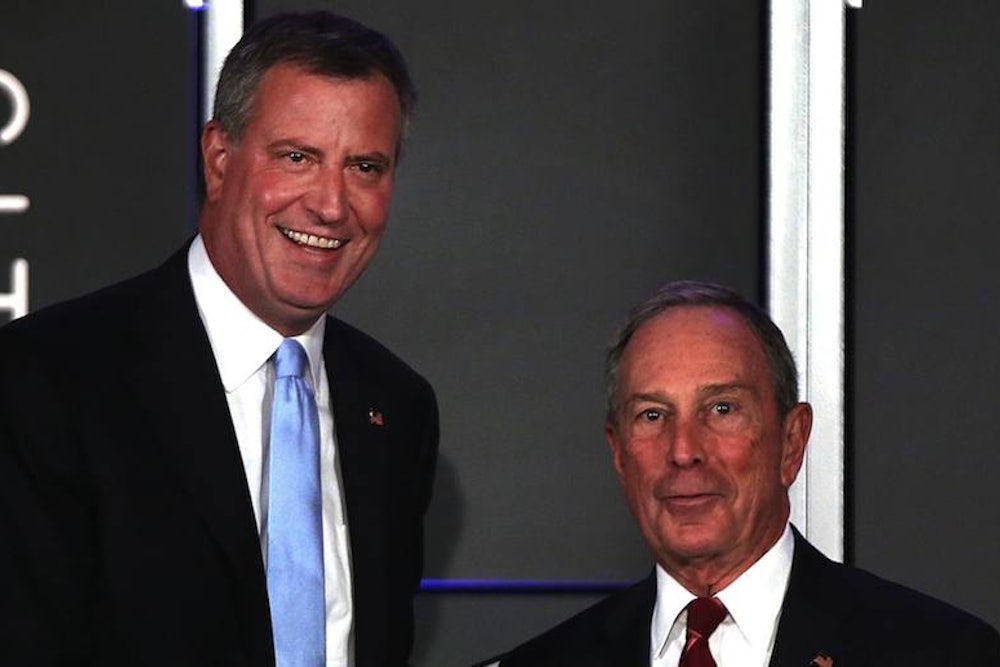

Such is the impact de Blasio has had on the discourse that at a forum yesterday at which, for the first time, he and Lhota appeared together (though they never shared the stage), even Lhota nodded in that direction. Moderator Walter Isaacson—current Aspen Institute head and former Time editor, and therefore the walking, breathing, Southern-drawling incarnation of the conventional wisdom—similarly felt obliged to ask Lhota, “Is it the role of city government to decrease the role of inequality?” Oh, and right, presiding was the man who has reigned over all this inequality and whom de Blasio has ridden virtually all the way to City Hall by trashing: Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

The panel, which closed the conference, was, one felt, Bloomberg’s shindig. It was most immediately notable, as The New York Times reports, for Bloomberg’s careful easing into the role of ex-mayor and elder statesman. “Here in New York City, voters will go to the polls next month to elect a new mayor,” he declared. “I have said this a thousand times: I have always believed that—I hope the next administration will be so successful, even more successful than our administration has been.”

But what was most compelling about the event, which at times took on the quality of a cheerleading summit for that “Urban Solutions to Global Challenges” theme—I mean, how soon til the Start-Up City book?—was how well it meshed with the shutdown. Lhota and de Blasio take different positions on policing, taxes, housing, education (maybe education most of all), and pretty much every other issue that a mayor without a $31 billion fortune at his disposal can plausibly tackle. On Tuesday, they continued to take those different positions, albeit with unusual politesse. By contrast, they agreed on just two things: The eminence of their host; and the sense that New York City, and the cities, are in it alone. “We no longer have a partner in Washington. We no longer have a partner in Albany,” Lhota said, speaking directly about affordable housing but indirectly about everything. “We’re going to have to do it on our own.” De Blasio echoed this:

National governments in our time are failing to serve as catalysts for action, requiring cities to fill the void with creativity and innovation. Yet the problem seems particularly pronounced here at home. While there was a time when innovation in the United States was driven at the federal level—the New Deal, the space program, the GI Bill, the mapping of the human genome are extraordinary examples—today we’re not seeing Washington offer solutions to the unique challenges of our time. Instead we see shutdowns. I firmly believe that some of the challenges our cities face are too vast for us to wait. It’s why in the 21st century, at least for the foreseeable first part of it, cities, led by many of the officials and experts here today, must be laboratories for reform and the primary problem-solvers.

It all felt a little too neat and convenient in that impossible-to-miss, technocratic, Bloomberg-y way. Big action still requires big governments; all the activist ordinances on and across the planet will be no substitute for a working U.S. federal government. Besides, even if “Global Challenges” really could be solved with “Urban Solutions,” it seems hard to believe the huddled masses munching salad and sipping iced tea in the second-floor conference room in the Financial District Tuesday are going to be where it all starts.

On the other hand, the trends are unmistakable. More than half of humanity lives in a city, for the first time ever. By the middle of the century, 70 percent will. And as for New York, Bloomberg, and de Blasio: if you can make it here …