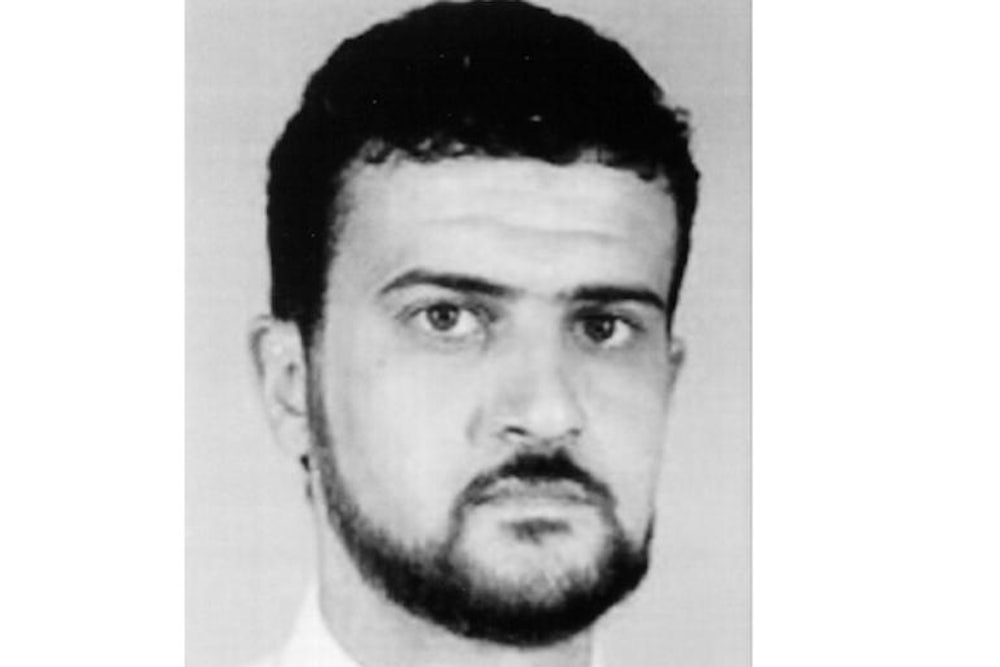

The United States’ handling of Al-Qaeda operative Abu Anas Al-Liby, seized over the weekend, broadly resembles its handling of another high-profile counterterrorism capture, in 2011: that of Ahmed Abdulkadir Warsame, a commander in Somalia’s al Shabaab and a broker of weapons transfers to that group from Al-Qaeda’s Yemeni affiliate. Like Al-Liby, Warsame was captured abroad, detained on a U.S. Navy ship under the laws of war, and interrogated by military and intelligence personnel. And like Warsame was, Al-Liby will—after some period of detention—presumably be moved to the criminal system. It’s a one-two combination of military detention and civilian criminal justice, which the Obama administration has pioneered.

And yet the case against Al-Liby, a suspect in a long-running Al-Qaeda prosecution, is somewhat different from Warsame’s, in that Al-Liby has been under indictment for more than a decade. This stands to bolster the United States’ position, once it shifts from detention and intelligence gathering to prosecuting Al-Liby for his role in a sprawling terrorism conspiracy that included two 1998 attacks on U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

Warsame’s seaborne interrogation went on for two months before the alleged Somali terrorist was told of his rights under criminal law. Once Warsame received the familiar Miranda advisories, he proceeded each day to waive his rights. And after being questioned by intelligence gatherers (un-Mirandized) and then law enforcement personnel (Mirandized), he was whisked ashore to the United States for criminal trial.

This hybrid of detention and interrogation, followed by advice of rights and civilian prosecution, posed some legal risks. Its first phase risked a threshold challenge by Warsame’s criminal defense lawyers; equally likely was an attack on Warsame’s waivers of his rights during the second phase, which had to be knowing and voluntary in order to stand up in court.

But whether or not it should have given a court pause, the government got away with it: Warsame opted to cooperate with federal investigators and ultimately pleaded guilty.

Which brings us to Al-Liby. Right now, he too is undergoing intelligence interrogation aboard a naval vessel—and, like Warsame, without first having been advised of his rights. If the Obama Administration keeps with the Warsame playbook, then federal investigators eventually will take over, recite the usual legal admonitions, and then seek to prosecute Al-Liby in a federal courthouse. Of course we cannot yet know what Al-Liby’s intentions are. He might play along, as Warsame did. But he might not, and instead object to his unwarned interrogation or contest the government’s evidence. If so, will the United States’ two-pronged approach then prove harmful, or even fatal to the latest installment in the Embassy Bombings case?

I suspect not. From the prosecution’s standpoint, the risks are significantly lesser in Al-Liby’s case than they were in Warsame’s. Here’s why.

Once a defendant is in custody, two general requirements come into play: Miranda, and the rule that an arrested defendant must be taken “without unnecessary delay” to a federal judge. (The latter is known as “presentment.”) The criminal law typically deals with the government’s violation of one or the other (or both) by excluding statements obtained from the defendant as a consequence of the violation. And while the exclusionary rule might have got prosecutors’ nerves up in Warsame’s case, it almost certainly won’t in Al-Liby’s. The reason is that prosecutors likely won’t need to rely on any confessions that might come out of Al-Liby’s time at sea, regardless of whether he decides to talk to the government.

The government clearly already has other evidence against Al-Liby. A New York grand jury returned a still-pending indictment against him and many others in 2000. That certainly implies the prosecution’s confidence in its ability to convict each of the named defendants, Al-Liby included, beyond a reasonable doubt—and on the strength of evidence available more than a decade ago, and long before the Libyan’s capture this weekend. We likely know what some of that evidence will be.

Consider, for example, British police’s 1999 seizure of the famous so-called “Manchester Manual,” a detailed, DIY instructional for terrorists—from Al-Liby’s apartment in England. There’s also trial testimony from two cooperating witnesses in the Embassy Bombings prosecution, both former Al-Qaeda insiders, who implicated Al-Liby—and who presumably would do so again, if the time came. In 2001, the first of the pair told a New York jury that Al-Liby was in charge of running Al-Qaeda’s computers. The second confirmed Al-Liby’s computer duties in Al-Qaeda, while also testifying that in the early nineties, Al-Liby and others set up a makeshift darkroom for developing pictures, in the witness’s Nairobi apartment; and further that the witness once met Al-Liby, who had a camera, on the same street as the U.S. embassy in Nairobi.

From the look of things, the United States already can make a case against Al-Liby, and seemingly without having to introduce any statements he might make during an unwarned, Warsame-like interrogation at sea. If that’s right, then a defense challenge founded on Miranda or presentment won’t alter the outcome: there won’t be any new statements of Al-Liby’s to exclude.

Does that mean defense counsel simply will let the matter of Al-Liby’s military detention drop altogether? No. But it likely does mean that, in coming criminal proceedings, the Obama Administration’s two-pronged strategy could be more difficult to assail.

Wells Bennett is a Fellow in National Security Law at the Brookings Institution, and Lawfare's Managing Editor.