The recent revival of interest in Poe has brought to light a good deal of new information about him and supplied us for the first time with a serious interpretation of his personal career, but it has so far entirely failed to explain why we should still want to read him. In respect to such figures as Poe, we Americans are still perhaps almost as provincial as those of their contemporaries who now seem to us ridiculous for having failed to recognize their genius: today, we take their eminence for granted, but we cannot help persisting to regard them, not from the point of view of their real contributions to the development of western culture, but primarily as fellow Americans, fellow provincials like ourselves, whose activities we feel the necessity of explaining in terms of America and the peculiar circumstances of whose lives we are, as neighbors, in a position to investigate. Thus, at a date when “Edgar Poe” has figured in Europe for the last three-quarters of a century as a writer of the first importance, we in America are still preoccupied—though no longer in moral indignation—with his bad reputation as a citizen. Thus, Dr. J. W. Robertson, perhaps the initiator of the present investigation, five years ago published a book to show that Poe was a typical alcoholic. Thus, we have recently had the publication of Poe’s correspondence with his foster-father. Thus, we are promised the early revelation of Poe’s plagiarism of his plots from a hitherto unknown German source (as James Huneker has pointed out that Poe’s later and most celebrated poems must certainly have been imitated from an obscure American poet named Chivers). Thus, Miss Mary E. Phillips has recently published an enormous and entirely uncritical biography of sixteen hundred and eighty-five pages (Edgar Allan Poe, the Man: the John C. Winston Company), one of those monuments of undiscriminating devotion which it must have taken a lifetime to compile, stuffed with illustrations ranging from photographs of the harbor of the Scotch town from which Poe’s foster-father came, the librarian of the University of Virginia at the time when Poe was a student there and the clock on the mantelpiece of Poe’s cottage at Fordham, to maps of Richmond, Baltimore and New York at the time when Poe lived in them; and bearing embedded in the pudding-stone of its prose a larger number of actual facts about the poet than have perhaps ever before been assembled.

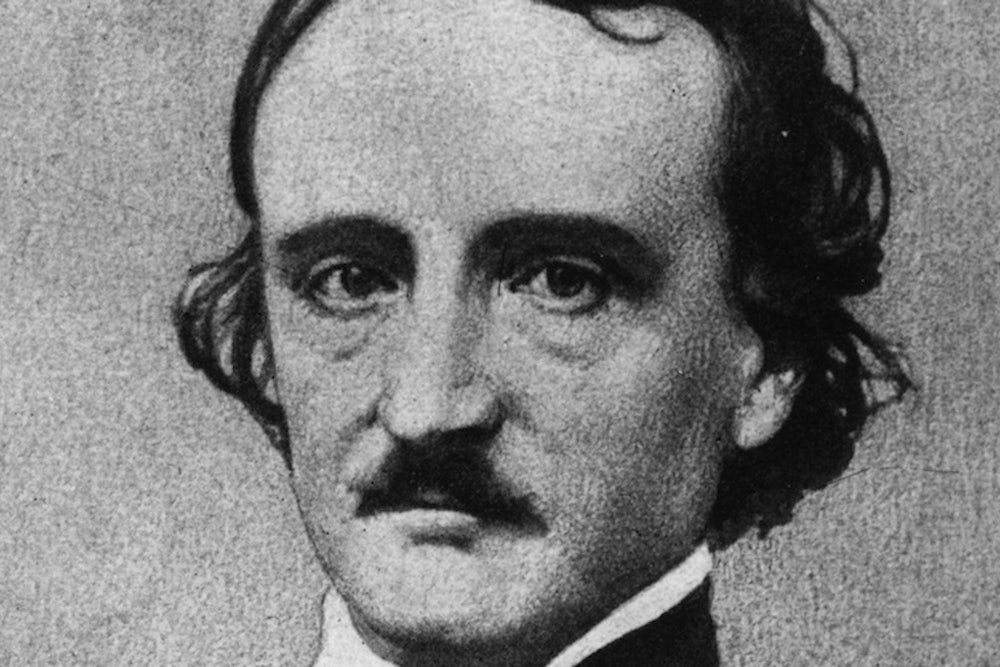

The ablest and the most important of recent American writings about Poe has without doubt been Mr. Joseph Wood Krutch’s Edgar Allan Poe: A Study in Genius. Mr. Krutch has attempted to go beyond Doctor Robertson in diagnosing Poe’s nervous malady and his conclusions are by this time well known: he believes that Poe was driven into seeking a position of literary eminence by a desire to compensate himself for the social position of which his foster-father had deprived him; that, perhaps by reason of a “fixation” on his mother, he was sexually impotent and forced, as a result of his inability to play a part in the normal world, to invent an abnormal world dominated by feelings of horror, repining and doom (the universally recognized concomitants, according to Mr. Krutch, of sexual repression of this sort), among whose dreams he could take refuge; that his intellectual activity, his love of reasoning over cryptograms and crimes, was primarily stimulated by a desire to appear logical in face of the fact that, as a consequence of his psychological maladjustment, he knew that he was going insane; and, finally, that his critical theory was merely a justification of his artistic practice, which was thus itself merely, in turn, the symptom of his disease. It must be said, in fairness to Mr. Krutch, that he does not fail, in the last pages of his book, to draw, the general conclusions about artists in general which follow from his particular conclusions about Poe: he fully admits that, if what he says about Poe is true, it must also he true of “all imaginative works,” which, in that case, should be regarded as the products of “unfulfilled desires” springing from “either idiosyncratic or universally human maladjustments to life.” This does not, however, prevent Mr. Krutch from misunderstanding and underestimating Poe’s writings from the point of view of their literary value, nor even from complacently caricaturing them—as the modern school of social-psychological biography, of which Mr. Krutch is a typical representative, seems inevitably to tend to caricature, as Mr. Krutch does, also, the personalities of its subjects. Thus, we are nowadays edified by the spectacle of all the principal ornaments of the race exhibited in terms of their most distressing humiliations, their most ridiculous manias, their most disquieting neuroses and their most lamentable failures. Mr. Krutch has chosen for the frontispiece of his “study in genius” a daguerreotype of Poe taken shortly before his death in 1849: it shows a dilapidated and pasty individual with untrimmed, untidy hair, an uneven toothbrush mustache and large pouches under the eyes; the eyes themselves have a sad unfocussed stare; one eyelid is drooping; one hand is thrust into the coat-front with an air of feeble pretentiousness; the solemn dignity of the whole figure seems as ludicrous as that of a bad actor attempting to play Hamlet, at the same time that its disintegration makes us as uncomfortable as that of an alcoholic patient just admitted to a cure. And it must be confessed that this is the final impression which Mr. Krutch leaves us of Poe. Mr. Krutch quotes with disapproval the memorable statement of President Hadley of Yale, in explanation of the refusal of the committee of the Hall of Fame to admit Poe among its immortals: “Poe wrote like a drunkard and a man who is not accustomed to pay his debts.” Yet Mr. Krutch himself, so interesting as a psychologist, is perhaps almost as far astray in his values, when he says, in effect, that Poe wrote like a dispossessed southern gentleman, a man with a fixation on his mother.

For the rest, Mr. Mencken has written with admiration of Poe’s destructive reviewing of his contemporaries-—that is, he has paid a tribute to an earlier practitioner of a special art of his own. Mr. Brooks has examined Poe’s work for evidences of the harshness and sterility of a Puritan-pioneer society and found it unsatisfactory as literature. And Mr. Mumford, in his new book on America, seems to have taken his cue from Mr. Brooks and sees in the hardness of some of Poe’s effects merely the iron of the industrial age. It is perhaps true that no recent American critic, with the exception of Mr. Waldo Frank in his notice of the Poe-Allan letters, has written with any real appreciation of Poe’s absolute artistic importance.

One of the most striking features of all this American criticism of Poe is its tendency to regard him as a freak, having his existence somehow apart both from literature and from life. “That his life happened to fall,” writes Mr. Krutch, “between the years 1809 and 1849 is merely an accident, and he has no more in common with Whittier, Lowell, Longfellow, or Emerson than he has with either the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries in England. ... His works bear no conceivable relation, either external or internal, to the life of any people, and it is impossible to account for them on the basis of any social or intellectual tendencies or as the expression of the spirit of any age.” And, worse than this, we are always being told that Poe has no connection with “reality,” that he writes exclusively of a “dream world” which has no significance for our own. The error of this second objection becomes apparent when we consider the obvious falsity of the first. So far from having nothing in common with the spirit of the first half of the nineteenth century, Poe is certainly one of its most typical figures; that is to say, he is a thorough romanticist, closely akin to his European contemporaries. Thus, his fantasy is precisely that of Coleridge; his poetry precisely that of Shelley and Keats; his “dream fugues” precisely those of De Quincey and his “prose poems” those of Maurice de Guerin; and his themes —which, as Baudelaire says, are concerned with “the exception in the moral order”—precisely those of Chateaubriand and Byron, and of the romantic movement generally. It is, then, in terms of romanticism that we must look for reality in Poe. We must not expect of him the same sort of treatment of life that we get from Dreiser or Sinclair Lewis and the preoccupation with which seems so to mislead modern American criticism of him. In other words, we must not expect of him “realism” at a time when realism had not yet arrived. From the modern naturalistic, sociological point of view, the European writers whom I have named above had no more connection with their respective countries than had Poe with America. Their settings and their dramatis personae, the images by which they rendered their ideas, were as different as those of Poe from the images of modern naturalism, and they aimed through them at different dramas, of which the morals were different truths.

What, then, are the morals of Poe, the realities he tried to express? The key is to be found in Baudelaire’s phrase about “the exception in the moral order.” The exception in the moral order was the predominant theme of the whole romantic movement. It is absurd to complain, as our critics are always doing, of Poe’s indifference to the large interests of society, as if this indifference were something abnormal: one of the principal features of romanticism was, not merely an indifference to the claims of society, but’ an exalted revolt against them. The favorite figure of the romantic writers was the individual sympathetically considered from the point of view of his non-amenability to convention or law. And in this, Poe runs absolutely true to type: his heroes are the brothers of Rolla and Rene; of Childe Harold, Manfred and Cain. Like these latter, they are superior individuals who pursue extravagant curiosities or fancies; plumb abysses of dissipation; or indulge forbidden passions (Poe made one or two experiments with the classical romantic theme of incest; but his specialties were sadism and a curious form of adultery which never took place until after the woman to whom the hero proved faithless was dead.) And, as in the case of the other romantic heroes, the drama of their situation arises from their conflict with human or divine law.

The individual’s impulse, however, in Poe rarely wears, as it often does with the other romantics, the aspect of a too generous passion overflowing the canals of the world; but takes on rather the sinister character of the “Imp of the Perverse.” Yet the perversity of Poe, the dizzy terror which it engenders—due to whatever nervous instability and whatever unlucky circumstances—have their poetry and their profound pathos—from those lines in one of the finest of his poems in which he tells how the doom of his later life appeared to him even in childhood as he gazed on “the cloud that took the form (when, the rest of Heaven was blue) of a demon in my view”; to that terrible picture of the condemned man, “sick—sick unto death with that long agony,” when “first [the candles] wore the aspect of charity, and seemed white slender angels who would save me; but then, all at once, there came a most deadly nausea over my spirit, and I felt every fibre in my frame thrill as if I had touched the wire of a galvanic battery, while the angel forms became meaningless spectres, with heads of flame, and I saw that from them there would be no help. And then there stole into my fancy, like a rich musical note, the thought of what sweet rest there must be in the grave.” And it is the “long agony” of his moral experience that gives to Poe’s William Wilson its superior intensity and sincerity over Stevenson’s Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In Stevenson’s story, it is the noble half of the dual personality which, though at the price of its own destruction, triumphs over the evil; whereas, in Poe’s, it is the evil half which puts to death the good and which is even made to tell the whole story from its own point of view. Yet, does not the reality of William Wilson make us shudder in the presence of the abyss far more readily than the melodramatic fable of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde?

There is one special tragic theme of Poe’s which deserves to be noted in this connection. Mr. Krutch says that Poe was impotent and that, for this reason, though perhaps unconsciously, he chose as a wife a girl of thirteen with whom it would be impossible to consummate his marriage. Mr. Krutch offers no proof for this assertion and it is not necessary to assume that it is true; but it is quite evident that Poe’s marriage with Virginia was somehow unsatisfactory. It may be that, because Virginia was his first cousin, he had scruples about having conjugal relations with her. In any case, Virginia became tubercular and, twelve years after she was married, died; while Poe himself became neurotic, irritable and obsessed by desperate fancies, and finally went insane. It is surely possible to follow Mr. Krutch so far as to admit that the atrocious sadism of many of Poe’s later tales may have been the result of some emotional repression. And he must often have wished Virginia dead at the same time that he adored her. Pie is always imagining, in his tales, long before Virginia’s actual death, that a woman like Virginia has died and that her lover is free to love other women. But, even here the dead woman intervenes: in Ligeia, she reincarnates herself in the dead body of her successor; in Morella, in her own daughter. And it is evidently the conflict of his emotions about Virginia which inspires, not merely these bizarre fancies, but also the unexplained feelings of remorse which often haunt Poe’s heroes. After her death, the situation he has foreseen appears exactly to be realized. He conducts flirtations with other women; but they are accompanied by “a wild inexplicable sentiment that resembled nothing so nearly as a consciousness of guilt.” He is at one time on the point of getting married; but abruptly causes the engagement to be broken off. “I was never really insane,” he writes to Mrs. Clemm just before his miserable death, “except on occasions when my heart was touched. I have been taken to prison once since I came here for getting drunk; but then I was not. It was about Virginia.” The story of Poe and Virginia is a painful and rather unpleasant one; but it is perhaps worth discussing to this extent: we recognize in it the actual situation which, viewed in the light of a romantic problem and transposed into romantic terms, fills Poe’s writings with the ominous sense of a deadlock between the rebellious spirit of the individual will, on the one hand, and both its very romantic idealisms and its human bonds, on the other. “The whole realm of moral ideals,” says Mr. Krutch, “is excluded [from Poe’s work], not merely as morality per se, but also as artistic material used for the creation of conflicts and situations.” What, then, does he suppose such stories as Ligeia and as Eleonora are about? He goes on to say that horror is the only emotion which is “genuinely Poe’s own” and that this “deliberately invents causes for itself,” that “it is always a pure emotion without any rational foundation.” What is the moral interest, he would no doubt ask, of the Case of M. Valdemar or of the Descent Into the Maelstrom? I propose to discuss this question in a moment.

Poe was, then, a typical romantic. But he was also something more. He contained the germs of a further development. By 1847, Baudelaire had begun to read Poe and had “experienced a strange commotion”: when he had looked up the rest of Poe’s writings in the files of American magazines, he found among them stories and poems which he had “thought vaguely and confusedly” of writing himself and Poe immediately became an obsession with him. In 1852, he published a volume of translations of Poe’s tales; and from then on, the influence of Poe became one of the most remarkable in French literature. M. Louis Seylaz has recently traced this influence in a book called Edgar Poe et les Premiers Symbolistes Francais, in which he discusses the indebtedness to Poe of the French symbolist movement, from Baudelaire, through Verlaine, Rimbaud, Mallarme (who translated Poe’s poems), Villiers de L’Isle-Adam and Huysmans, to Paul Valery in our own day (who has just written some interesting pages about Poe in a preface to a new edition of the Fleurs du Mal).

Let us inquire precisely in what this influence consisted which was felt so profoundly through a whole half- century of French literature, yet which has so completely failed to impress itself upon the literature of Poe’s own country that it is still possible for Americans to talk about him as if his principal claim to distinction were his title to be described as the “father of the short story.” In the first place, says M. Valery, Poe brought to the romanticism of the later nineteenth century a new discipline: perhaps more than any other French or English writer of his school, he had thought seriously about the methods and aims of literature: he had formulated a critical theory and he had supplied specimens of its practice. Even in poetry, by the time that Poe’s influence had begun to be felt, it was naturalism which had been brought into play on the part of the post-romantic generation against the looseness and the extravagance of romanticism running to seed. But Poe provided them with a new and logical program which lopped away many of the overgrowths of romanticism and yet aimed at ultra-romantic effects. What were these ultra-romantic effects at which Poe aimed and what were the means by which he proposed to attain them?

“I know,” writes Poe, “that indefiniteness is an element of the true music [of poetry]—I mean of the true musical expression . . . a suggestive indefiniteness of meaning with a view of bringing about a definiteness of vague and therefore of spiritual effect.” This is already the doctrine of symbolism. Poe had exemplified it in his own poems. Poe’s poetry is rarely quite successful; but it is, none the less, of first-rate importance. He speaks somewhere of poetry as the pursuit to which he would have desired, under happier circumstances, to have devoted his principal efforts, or something of the sort; and it is certainly true that the immaturity of his early verse is scarcely adequately redeemed by the deliberate tricks of his later; these devices seem all to have been borrowed from Chivers, who, though he provided a readier road to the popular ear, was certainly, on the whole, a far less desirable master for Poe than Shelley and Coleridge had been. Yet all Poe’s poetry is interesting because more than that of any other romantic (except perhaps Coleridge in Kubla Khan), it does approach the indefiniteness of music—that supreme goal of the symbolists. That is to say, from the ordinary point of view, Poe’s poetry is more nonsensical than that of any other of the romantics—and nonsensical in much the same way as, to the ordinary point of view, modern poetry appears. To note but a single instance: one of the characteristic symptoms of modern symbolism is a sort of psychological confusion between the impressions of the different senses. And this confusion distinctly appears in Poe: thus, he hears, in one of his poems, the approach of the darkness; and, in the marvelous description in one of his tales of the non-sensuous sensations which follow death, we read that, “night arrived; and with its shadows a heavy discomfort. It oppressed my limbs with the oppression of some dull weight, and was palpable. There was also a moaning sound, not unlike the distant reverberation of surf, but-more continuous, which, beginning with the first twilight, had grown in strength with the darkness. Suddenly lights were brought into the room . . . and issuing from the flame of each lamp, there flowed unbrokenly into my ears a strain of melodious monotone.

And Poe’s theory of short story writing was similar to his theory of verse. “A skilful literary artist,” he writes, “has constructed a tale. If wise, he has not fashioned his thoughts to accommodate his incidents; but having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents—he then combines such events as may best aid him in establishing this preconceived effect.” So the real significance of Poe’s stories does not lie in what they purport to relate. Many of them are confessedly dreams (usually nightmares); and, like dreams, at the same time that they appear absurd, their effect upon us is serious. And even those which pretend to the accuracy and the logic of realistic narratives are dreams, none the less. They are quite different from the mere macabre surprises and stories of astonishing adventure of even such imitators of Poe as Conan Doyle. The descent into the maelstrom is like a metaphor for the horror of the moral whirlpool into which, as we know from more explicit stories, Poe had a giddy apprehension of being sucked; and M. Valdemar, for the horror of death, or rather of death endured by the living, which, from whatever blighting of some area of his nature, haunted Poe throughout his later life. No one understood better than Poe that, in fiction and in poetry, it is not what you say that counts, but what you make the reader feel (he always italicizes the word “effect”); no one understood better than Poe the possibilities for rendering deep truth through phantasmagoria than Poe, with whom his most circumstantial realism is phantasmagoria like the rest—as, indeed, all realism must, at bottom, be. And he is a writer who should particularly interest us today, when the revolt against the superficiality and literalness of the naturalistic movement which intervened between Poe’s time and ours seems constantly to be gathering strength.

“Poe’s mentality was a rare synthesis,” writes Mr. Padraic Colum. “He had elements in him that corresponded with the indefiniteness of music and the exactitude of mathematics.” Is not this precisely what modern literature tends toward? Poe was the bridge over the middle nineteenth century from romanticism to symbolism; and symbolism, as M. Seylaz says, though scarcely any of its accredited exponents survive, now permeates literature. We must not, however, expect Poe to be admired, in his capacity of suspension across this chasm, on the part of American writers who do not know that either bank exists.