For a few brief moments on Monday evening, it looked like House Republicans might finally come to their senses.

At a little past 6 p.m., CNN and National Review reported that Peter King, the congressman from New York, was organizing an insurrection among a group of fellow moderate Republicans. It happened just as the House was preparing to vote on yet another “continuing resolution” that would shut down the government if Senate Democrats and President Obama wouldn’t agree to undermine Obamacare. For weeks, high Senate Republicans like Bob Corker and Lindsey Graham had warned their House counterparts not to insist on such a strategy: Obama and the Democrats would never agree to it and, in a shutdown, Republicans would take the blame. Now King, who had already suggested he agreed with that critique, decided to do something about it. He started working the phones, hoping to rally enough votes to stop the spending bill from passing.

All he needed were 17 votes. He got six. And nobody should be surprised.

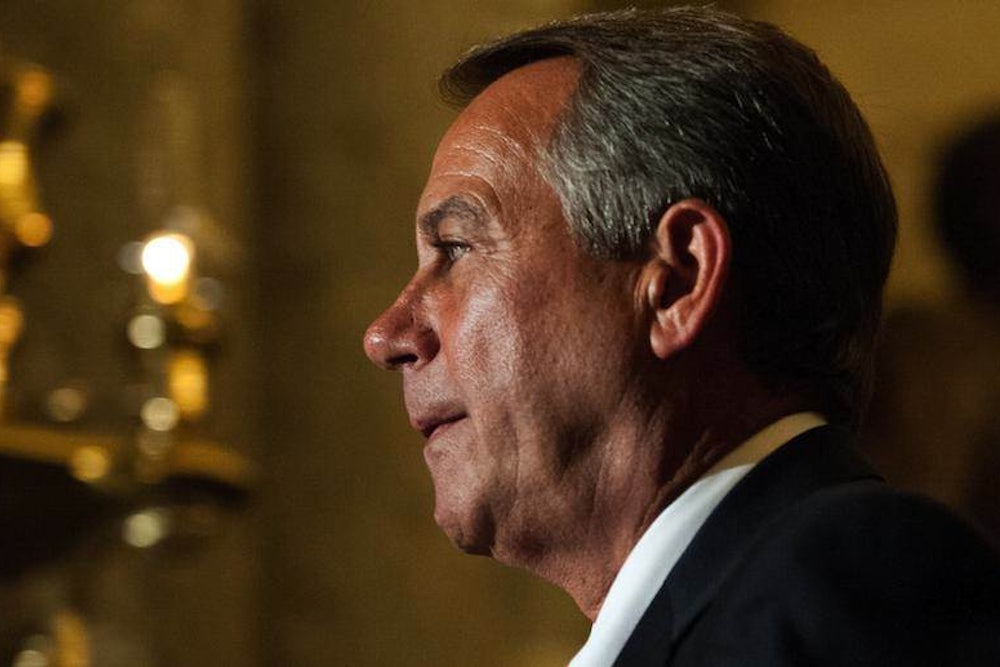

At midnight, the government shut down. Nobody knows when it will open back up. And outside of Washington, many people will probably think it’s business as usual in capital—in other words, that both parties are to blame. But nothing could be farther from the truth. This is a serious break with governing norms—a temper tantrum, by one faction of one party. But as with most temper tantrums, you can’t simply blame the kids acting out. You also need to blame the grown-up letting it happen. That means House Speaker John Boehner.

To be sure, debating how to finance government operations is always a lively and difficult debate. But it doesn’t typically involve one party demanding repeal of an existing law—and threatening to shut down the government, or cause a federal default, if they don’t win. Conservative Republicans have said they merely want President Obama and the Democrats to compromise, but Obama and the Democrats have already compromised. In fact, they’ve already conceded, at least for the immediate future. Both Obama and Senate Democrats have said they would agree to temporarily funding the government at the sequestration levels—something Republicans say they support but Democrats oppose strongly. On Monday, Democratic leaders in the House said they were willing to do the same thing. In a press conference, Democratic Whip Steny Hoyer asked, “Will they take ‘yes’ for an answer?” Republicans quickly made clear the answer was “no.” Any funding bill that doesn’t gut Obamacare, they said, is unacceptable.

Republicans have also suggested that, by proposing merely to delay Obamacare’s individual mandate, they were making a major concession. This is even more laughable. Delaying the individual mandate now, with Obamacare’s insurance exchanges hours from launching, would wreak some havoc: Insurance companies have already set prices for their products, assuming the mandate would be in place. And as multiple analysts have argued, taking the individual mandate out of the law would increase premiums and reduce enrollment—maybe not enough to destroy the law completely, but enough to weaken it significantly and introduce serious new instability. But you don’t need to listen to the analysts. You need only listen to the Republicans and their more passionate allies, who have been pushing delay explicitly because, they promise, it will eventually unravel the law.

Of course, the shutdown—and threats to induce default—are simply the latest manifestations of a campaign to undermine Obamacare that’s been underway ever since it became law. At both the federal and state levels, officials and their allies have actively worked to undermine the law’s implementation, whether by warning professional sports leagues not to make people aware of the law, making it difficult for counselors to advise people who want to apply for its benefits, or persuading young people to boycott the program altogether. Norman Ornstein, the American Enterprise Institute scholar and co-author of It's Even Worse Than It Looks, has called this campaign of sabotage "unprecedented." As Ron Bronwstein, the veteran National Journal columnist, noted, the last time a major political party openly resisted a duly passed law in this way was during the 1950s and 1960s, when the federal courts and the Congress acted to end segregation and establish equal rights for African-Americans.

The question hanging over this—the question nobody, to my satisfaction, has yet to answer—is why conservative Republicans feel so strongly about this. The basis for Obamacare, after all, is a coverage scheme that once had the imprimatur of the conservative Heritage Foundation. A version of it exists in Massachusetts, thanks to a governor who was not only a Republican but later the party’s presidential nominee. No, Obamacare isn’t identical to either the Heritage or Massachusetts models. Honest conservatives can cite reasons why the bill Obama signed is objectionable while those two models were not. But how on earth can conservatives justify such intense feelings—such vitriol—for a plan that bares at least strong resemblance to ideas they once thought were perfectly fine? Do they really feel as strongly as, say, whites during the '50s and '60s felt about segregation?

Maybe the Tea Party Republicans do. Maybe they believe all the stories about death panels and government demanding that people reveal medical histories in order to get health insurance. Maybe they really believe the individual mandate gives government unprecedented powers to control individual lives. Maybe they really believe it’s the end of Medicare and maybe even the end of our health care system as we know it. Most of these propositions don’t make a lot of sense to me, and some are flat-out untrue. But if you live in the right wing media bubble, it’s easy to believe they are real. And if they were, the resistance makes a little more sense.

But something else may be going on here. The willingness to shut down the government and allow default suggests these conservatives don’t accept the political legitimacy of Democrats—or, at least, certain Democrats. It’s surely no coincidence that the same conservatives enthusiastic about going to the brink (and over the brink) in order to stop Obamacare are the same ones who at various times have questioned Obama’s ancestry and religion—and accused him of stealing the election with the help of nefarious left-wing groups. If you truly believe that the president isn’t legitimate, why would you think his laws are? And if his laws aren’t legitimate, then why wouldn’t you indulge in extraordinary measures to stop them?

But Tea Party Republicans don’t have to speak for the whole party. In fact, in Congress, they seem to be a minority of the Republican caucus—a loud, passionate minority, but a minority all the same. Plenty of Republicans think differently. In the Senate, sensible but still very conservative Republicans like Bob Corker, Tom Coburn, and Lindsey Graham have made clear they have no patience for Tea Party nonsense. The Washington Examiner’s Byron York has reported that as many as 175 House Republicans are prepared to vote for a “clean” continuing resolution that would fund the government without touching Obamacare.

At some point the party’s leaders need to speak up for their (apparently) silent majority. And "leaders" in this case means Boehner. He’s in a difficult position, for sure, but it’s partly one of his own making. Sometimes leadership means telling followers what they can and can’t do. In this case, that should have meant telling Tea Party Republicans they can’t get rid of Obamacare, because it became law, was upheld by the Supreme Court, and validated by a presidential election. Boehner tried to say something along those lines after the election, but conservatives howled and—as usual—he backed down, promising the right they’d get their chance. Now they expect it to happen.

It won’t. And at some point Boehner needs to say so. It will mean taking political risks, but that’s what leaders do. Ask Nancy Pelosi, who while speaker in 2008 pushed through the Troubled Assets Relief Program, a bill she knew would hurt its sponsors but was necessary to avoid a financial disaster. At a press conference on Monday, Pelosi alluded to that episode—and suggested, not too subtly, it was time for Boehner to show similar mettle. So far he hasn’t. That makes him not just complicit in what’s rapidly becoming a crisis of political legitimacy. It also makes him culpable.

Note: This item has been updated.