In honor of Banned Books Week, we're publishing our original reviews of frequently banned books. In this brief look at Invisible Man—Ellison's only novel published in his lifetime—the reviewer notes that Ellison is a master "at catching the shape, flavor and sound of the common vagaries of human character."

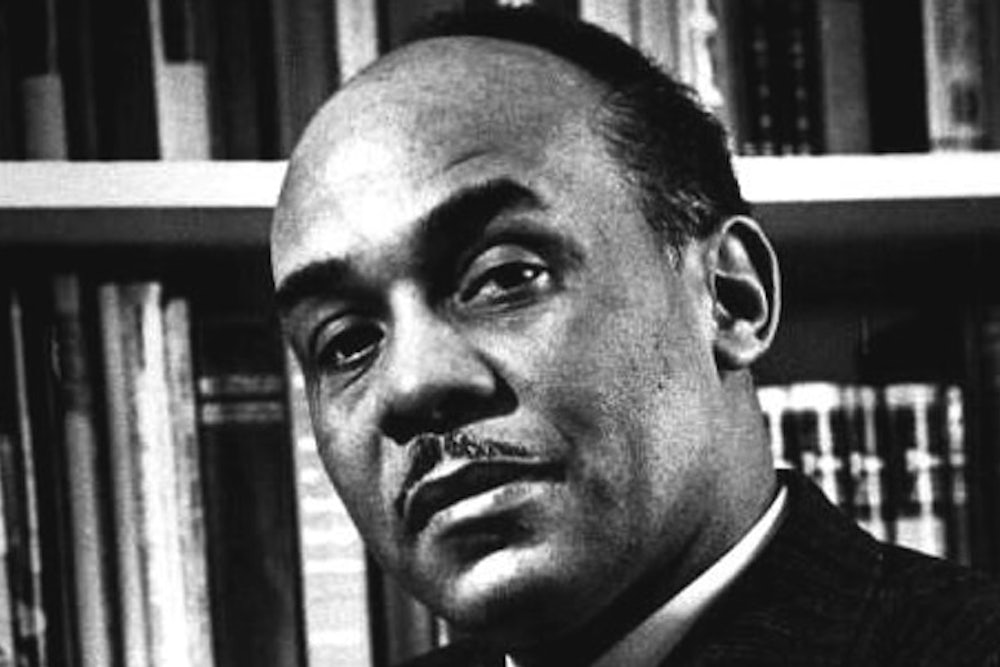

To paraphrase Graham Greene's already classic remark, "I am not a Catholic writer, but a writer who happens to be a Catholic," it can be said of Ralph Ellison that he is not a Negro writer, but a writer who happens to be a Negro. The parallels between these otherwise dissimilar novelists are that each within a brief space of time has written a book concerned with his dominating stigmata, semi-autobiographical, in the first person singular and yet in each instance the work of a writer whose writing as such overrides his preoccupation with, in Mr. Green's case, religion, and in Mr. Ellison's, race. In addition, both are masters at catching the shape, flavor and sound of the common vagaries of human character and experience.

Here the resemblances cease, and it is up to one's approach to fiction which author comes off on top. For Greene, who has it over Ellison in age and experience, is perhaps the finest living writer of the well-made book in which every word, sentence, paragraph and chapter is a dependent and contributor to a perfected whole. Ellison, whose first novel this is, although he already exhibits considerable technical maturity, has not yet achieved the integration of skill, experience and view of life necessary to the seriously ambitious novel. But in a time when the poles of fictional success have been reached by tidy little bundles of nothing and sprawling monsterpieces which appear to have gone directly from an adolescent's typewriter to the printer without benefit of editorial midwifery, it is a joy to encounter a vigorous imaginative, violently humorous and quietly tragic book that is informed with far more than the rudiments of the novelist's art.

It would be unfair in a necessarily brief review to go further than to outline Ellison's narrative or the thesis that underlies and controls it. This is the story of one man, born in the American South, whose exceptional abilities brought him educational opportunities and later in the North social and cultural "advantages" denied the vast majority of his race. It is a story told accurately and with a redeeming hilarity of a pensive disillusionment. On the road to invisibility, our pilgrim encounters the Southern small businessman, the Uncle Tom educator, the Northern do-gooder, the Negro military racist, the Harlem messiah with a sideline in numbers, the socio-scientific, highly organized Brothers whose Sisters most frequently discussed the dialectic in the boudoir, a journey that would have left Bunyan's Christian without care or hope for redemption. Ellison's solution, with a little aid from Dostoevsky and Kafka, is ingenious and original—perhaps a little too much so of both.

Invisible Man is a book shorn of the racial and political clichés that have encumbered the "Negro novel." It firmly establishes Ellison with that small group of writers—William Faulkner, Bucklin Moon, J. Saunders Redding—as an artist in handling his given material. The bane of the problem novel, in particular the "Negro novel," in America is that the cart of the subject has preceded the horse of artistic sensibility. Having given ample proof of the latter, it can be earnestly hoped that from the underground to which history and human frailty has driven him, Ellison can emerge to write of other places.