This piece originally appeared at newstatesman.com.

To the right of the grand staircase leading up to the circle at the Teatro Valle in Rome is a plaque that says the theatre hosted the premiere in 1921 of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. Now regarded as a modernist classic, the play shocked early audiences and was greeted with shouts of “Manicomio!” (“madhouse”) on its opening night. Today, the plaque is complemented by a more recent message, spelled out in pink stencilled lettering in English on the staircase: No Violence, No Homophobia, No Sexism, No Racism—repeated like a mantra as the steps stretch up into the darkness. “That’s from an event we did for Rome Pride,” says Valeria, my guide. “But we liked it so much, we decided to keep it.”

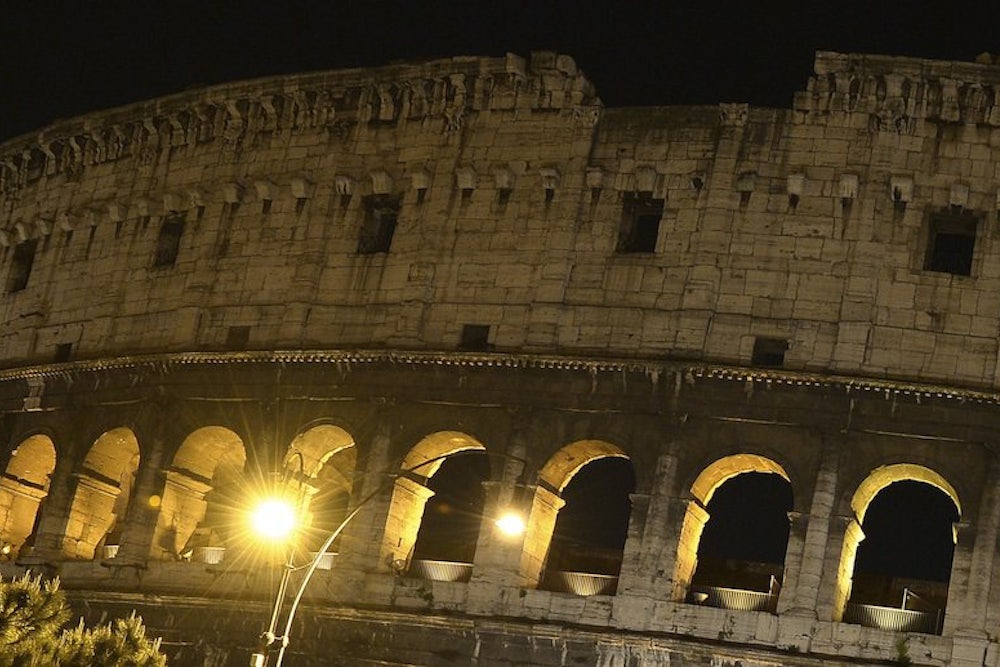

Built in 1727, and located up a narrow street halfway between the ancient Forum and the Pantheon, Teatro Valle is the oldest theatre in Rome. It has long been known for promoting innovative work—but now the building itself is home to a bold social experiment. In June 2011, after Rome’s city council threatened to close the theatre, actors and employees occupied it in protest. This was not an unusual step as such: as the eurozone crisis drags on, Italy’s cultural assets—referred to as petrolio italiano (“Italian crude oil”), because of their economic importance—have become a flashpoint for discontent. Art gallery and museum workers have been particularly restive as state funds have declined—and the Colosseum has become a focus for strikes.

But what began as a symbolic protest at Teatro Valle rapidly grew into something more. The occupation drew endorsements from some of Italy’s leading cultural figures, as well as thousands of messages of support from members of the public. Instead of leaving after three days as they had originally planned, the occupiers decided to stay and to keep the theatre running.

Valeria explains that they have tried to make the venue as welcoming as possible. “Older ladies come and bring us lunch, or newspapers,” she says. “People who would never dream of entering a squat come in. It’s created a centre of community in central Rome where there was none.”

Decisions are taken collectively: once a week, an open assembly is held in the theatre café, a room with tall glass windows that look on to the street, so that members of the public can see what’s happening and join in, if they want to. There, they discuss everything from the cleaning rota to the programming. “The point we are trying to make,” Valeria says, “is that there are things that cannot be managed by the public or the private. Some things cannot be privatised—schools, hospitals. But when the state cannot manage them properly, I the citizen should have the right to run it.”

August in Rome is usually a time of mass exodus, as city-dwellers escape the oppressive heat and head down south to the coast or up into the mountains of central Italy. At the start of the month, roads leading away from Rome are jammed and the emergency services work overtime to deal with traffic accidents. But, as a recent edition of Italian Vanity Fairmournfully reported, those days “no longer exist."

Italy is mired in its longest postwar recession and has suffered eight consecutive quarters of negative GDP. Fewer people are going on holiday, and those who do go away take shorter stays in cheaper hotels. In the past year, apartment purchases fell by a quarter nationally. Four million fewer phone calls were made, and 3.4 billion fewer litres of petrol were used. Above all, the unemployment rate has soared to more than 12 per cent. Personal savings—or, for younger Italians, 42 per cent of whom are out of work, the option of returning to live in the family home—have provided a cushion of sorts in recent years. But as an Italian friend told me, “This year, for the first time, we’re starting to see the savings run out.”

Public anger has turned towards Italy’s political class, its image already tarnished by the scandals of the Silvio Berlusconi years. At the general election in February, discontent manifested itself in a huge vote for the populist, anti-establishment Five Star Movement, led by the stand-up comedian Beppe Grillo. A few months later, Rome’s mayor, Gianni Alemanno, was kicked out of office after five years in power.

To many, Alemanno represented everything that was wrong with Italy’s political culture. Having begun his political career in the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement, he was minister of agriculture under Berlusconi from 2001-2006. Fascist salutes from a crowd of young Roman skinheads greeted his election as mayor in 2008 and there was a flurry of alarmed international press coverage. But his reign was less dramatic, even though it gave a stimulus to the various far-right fringe groups active in the city.

Guido Caldiron, a prominent political journalist and the author of a recent book on the extreme right, says Alemanno initially won support by exploiting anxieties about immigration and Roma gypsies, but he had no answers to the much more pressing economic problems. “He really did very little—there isn’t a single public initiative he undertook worthy of mention, while there are many shadows that accumulated along the way.”

Caldiron is referring to corruption—one of Alemanno’s close associates was arrested in March on suspicion of taking bribes. And so many former members of right-wing extremist organisations were given official jobs that the press named the influx into the city’s administration “fascistopoli."

Meanwhile, many public assets were sold off to private developers or otherwise left to decay. When in 2011 the government, under Berlusconi, closed the fund that administered Italy’s most important theatres and handed over control to local councils, there was good reason to fear for the future of Teatro Valle. Already, two historic cinemas had been sold. One is now a shopping mall for the luxury fashion brand Louis Vuitton; the other is slated to reopen as a casino.

Rome’s new mayor, the centre-left Ignazio Marino, has made encouraging noises about his commitment to culture in the city, but the immediate prospects do not look good. Nationally, politics has stalled. After the financial crisis forced Berlusconi from office in November 2011, Italy underwent a period of technocratic government, led by the economist Mario Monti, who imposed a programme of spending cuts and tax rises. This year’s elections, in which Grillo’s Five Star Movement came second, ultimately delivered a fragile governing coalition of centre left and centre right. Millions of Italians may have voted for change, but what they’ve got essentially is more of the same. Austerity continues apace and state funds for cultural projects keep on shrinking.

A few miles north of Teatro Valle, in a working-class suburb of Rome, I visited another occupied building. This one—now named Officine Zero, "Workshop Zero"—was a former train repair factory, sold to developers and then occupied by its workers with a little help from a student squat next door. On the afternoon I arrived, you could see how the place straddled the divide between two generations of the Italian left. In one of the workshops—surrounded by the dismembered carcasses of Trenitalia carriages—I saw a set of faded photos of the workers taking part in trade union demonstrations. Pride of place was given to a framed panoramic photograph of a huge rally in Rome in 1984: a sea of red flags, viewed from behind the head of a speaker on the platform.

In a tree-lined courtyard outside, some of those same employees seen in the photographs were sitting on plastic chairs in a circle, chatting quietly. The former train engineers have turned one corner of the factory into a recycling plant, and on the other side, office buildings have been converted into studio space by students, artists and writers. As Camilla, an Italian-language teacher involved in the project, explained to me, the recession has forced increasing numbers of young people into “freelance” employment, and working together like this is a way to overcome their isolation.

Italy has a long history of setting up squats and occupying social centres, but the financial crisis has helped them to flourish anew. In San Lorenzo, Rome’s university quarter, a sprawling network exists, little centres of community life. When I visited, one was hosting a swing dance class; another was providing study space for students shut out of university library buildings that now close early because of budget cuts. Shendi Veli, an activist with the long-running ESC Atelier social centre, explained to me that, “for many people, the only alternative to the crisis has been self-organisation.”

The occupation at Teatro Valle has tried to take this a step further. A few weeks after they first occupied the theatre, the activists invited the distinguished law professor Ugo Mattei to help them draw up documents that would give legal protection to their work—allowing them to continue running the theatre collectively. In 2007, Mattei had been a member of a commission of legal experts and jurists appointed by the government to make adjustments to Italian property law. They recommended a big change: to introduce a third category of property, neither public nor private, but “common.” When I contacted him by email, Mattei explained it was “based on access to and diffusion of power”; a challenge to the idea that the market knows best.

His proposals, which he describes as “anticapitalist” but transcending conventional left-right divisions, allow groups of ordinary citizens to take over public services and cultural institutions to stop them falling into private hands. In 2010, for instance, Mattei masterminded the successful campaign for a No vote in a referendum on whether Italy should privatise its water supply.

With the help of Teatro Valle, this has become a growing movement. Activists have held meetings in cities around Italy at which participants are invited to discuss local problems that could be fixed with collective action. In Pisa, the people talked about factory closures. In L’Aquila, the mountain city partly destroyed by an earthquake in 2009, residents aired their frustration at the lack of progress in rebuilding—and the laws that ban them from doing it themselves.

After several years of ignoring the commission’s proposals, the Italian Senate has just reopened discussions about whether to adopt formally the principle of “common” property. “We don’t need the state,” Mattei told me. “We need people organised from the bottom up, and that is why power is so scared of us.”

To Valeria, the experiment at Teatro Valle points to a new way of doing politics. “People think that participation means ‘give my opinion,'" she told me. “But we have a strong belief that politics is made with bodies.” We were sitting on the main stage as we talked. Actors had just been rehearsing there, and through the lights I could just make out the rows of empty red velvet seats, overlooked by ornate baroque balconies. Valeria continued: “When people from other towns ask, ‘How can I help Teatro Valle?’, we say, ‘Occupy a theatre in your own town.’”

Daniel Trilling is an assistant editor of the New Statesman.

This piece originally appeared at newstatesman.com.