In the late '90s, for five years, I taught at Harvard as a lecturer in the Department of English, where Seamus Heaney was Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory. Soon after my arrival, he invited me to dinner at the Dolphin, a little seafood restaurant on Massachusetts Avenue, which he liked. He said it was to be a “social evening, not a command performance,” knowing I would be nervous, and on a Tuesday after our classes, we met in the lobby of the Faculty Club to walk the few blocks to the Dolphin. Everywhere people recognized Seamus, greeting him eagerly, and he shook their hands, listened to what they had to say, and was always polite. The fact that we did not eat at the Club, amid the gloomy portraits of distinguished men, indicated to me it was indeed to be a social occasion.

At the restaurant, Seamus immediately ordered a bottle of Muscadet, and swallowing his first mouthful, he said that it was his eleventh year at Harvard and he no longer felt terrified returning. “Terrified about what?” I asked. And he replied that it was painful to leave his family for four months every year, and to interrupt his writing, in order to teach American students. His wife, Marie, who appears in many memorable poems, stayed on in Dublin with their young family, making it possible for Seamus to travel annually to Harvard. His friend Tomas Tranströmer, the Swedish poet, had recommended he never be apart from Marie for more than six weeks, and this was a formulation that had worked: he returned to Dublin periodically during the term. From the corner of my eye, I noticed a Cambridge poet and her husband at the next table listening intently, and when Seamus noticed them, too, he greeted them and then resumed our conversation.

To start, Seamus ordered cherrystone clams and I had a half-dozen oysters, which we ate raw, squeezing lemon juice on the creamy beige, slightly salty meat. A cherrystone clam is a hard-shell clam, with a thick, tough shell, and these were heart-shaped, with concentric growth lines, like those on a tree trunk. They’re the next step down from a quahog (pronounced CŌ-hog), a word I learned from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (“To be in any form, what is that?/ If nothing lay more developed, the quahog and its callous shell were enough./ Mine is no callous shell …”). My platter of oysters made me think of Seamus’s poem, “Oysters,” in which he describes them as “alive and violated,” and lying on “beds of ice,” and “ripped and shucked and scattered.” It is the opening poem in Seamus’s beautiful collection Field Work, which I read when I was a graduate student and just beginning to appreciate contemporary poetry, but I was changed by it, as unripe fruit is changed by the sun.

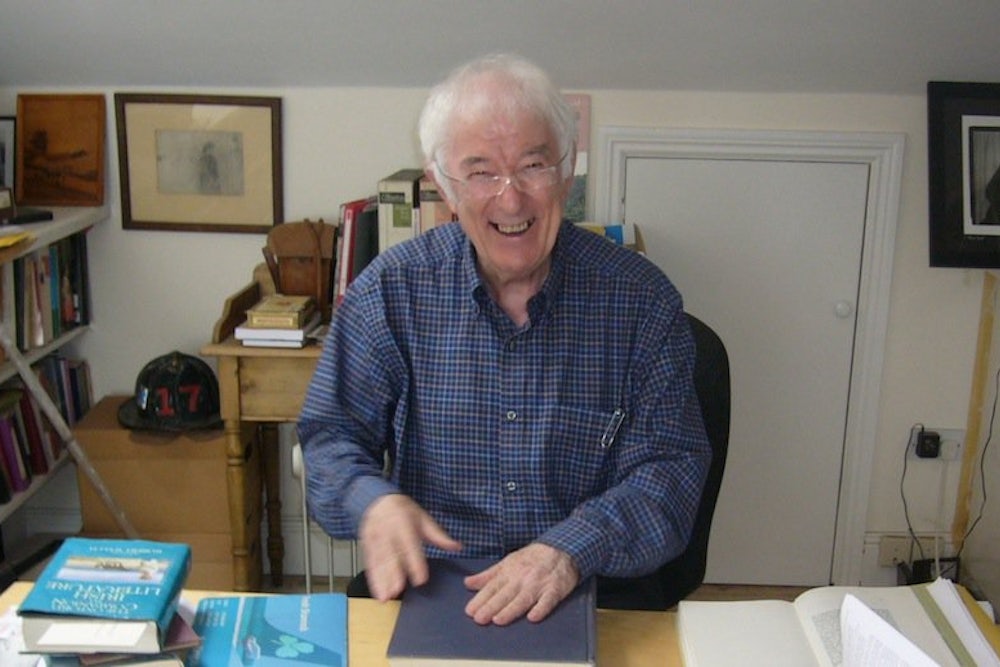

To dinner I wore blue jeans, boots, and an old fisherman’s sweater which had belonged to my friend Bill. Seamus wore a plaid shirt, with an open collar, and a handsome green suit of Irish wool, which I recognized from my interview many months earlier. It had been a sunny January afternoon and snow was heaped on the streets. During the interview, Seamus asked if I preferred poets who wrote in syllabics, as I was then doing, and I replied that I liked poetry that was not like mine.

During our meal, Seamus admitted he sometimes felt distant from American students but he wanted to continue teaching for six or seven more years before retiring. (A year later he won the Nobel Prize in Literature, which carried a purse of 7,200,000 Swedish kronor.) When Seamus traded one of his clams for one of my oysters, this made me happy because it seemed like a gesture en famille; later, after we had been colleagues for a couple of years, we traded fountain pens. He was autographing my copy of Crediting Poetry, his Nobel Lecture, with my high school Waterman pen and liked it so much I told him to keep it; in response to this, he reached in his coat pocket and gave me his nice Shaeffer, which I’ve never had the courage to write with, but it lies on my desk, a totem of friendship and creativity.

Seamus ordered boiled haddock for a main course, a fish I thought in keeping with his simple refinement. We talked about his new book, a version of Sophocles’ play “Philoctetes,” called The Cure at Troy, which I’d seen performed in New York City the previous spring. It had been a big success, and this brought Seamus pleasure. It was a classical play with a modern message regarding loyalty, a theme I knew to be relevant to Seamus’s poetry—the loyalty to oneself vs. the loyalty to one’s tribe, or, to put it another way, the loyalty to personal moral beliefs vs. the loyalty to political or religious callings. Of course, all poets must struggle with loyalty in order to overcome the boundaries of style, religion, race, gender and class, and national and ethnic identity, which inhibit us. Several years later, I learned that Seamus, raised a Catholic, was no longer practicing. He was committing himself instead to truth, or the truth of his own feelings, which is the basis of all art.

Seamus once began a lecture by thanking his colleague Helen Vendler for her introduction and adding that he always appreciated her truthfulness, especially when she was able to praise him. This made everyone in the audience laugh. He then went on to discuss two poems he loved as a young man: “To a Mouse,” by Robert Burns, a farmer poet, who one day turned up a mouse from its nest with his plough; the poem contemplates the destruction this wrought; and “The Yellow Bittern,” by Cathal Buí Mac Giolla Ghunna, an Ulster poet, who wrote in Gaelic. As on a wintry day he went walking near his home by the shores of Lough MacNean, he came upon a yellow bittern lying frozen on the ice; in his poem, Ghunna (a heavy drinker) speculates that the death was caused by the bird’s not being able to drink from the iced-over water. In both poems, a man confronts a creature in nature and this confrontation yields self-awareness. Also, both poems have two powerful currents of electricity running through them, a current from the English language (caused by the friction and song of words) and another current from the human experience language relates. Seamus seemed to be arguing that the poem of emotion WAS as important as the poem of language.

Recalling the gusto with which Seamus ate his haddock, I smile to myself because it is a durable fish, like him, inhabiting both the American and European coasts of the Atlantic Ocean. It feeds on most slow moving invertebrate, including small crabs, sea worms, clams, starfish, sea cucumbers, sea urchins and, occasionally, squid. The meat of the haddock is lean and white and flakes beautifully when cooked. The poetry is in the details.

When the bill for our dinner arrived, we were still eating key lime pie. Despite protests, Seamus paid for everything, and afterward we strolled down Massachusetts Avenue to the Café Pamplona, a tiny underground coffee shop, across the street from Adams House, the college residence where Seamus lived every winter and spring. It was smoky and claustrophobic but rather appealing, too.

Over the years, I took many things he said under advisement. When I published my fourth collection of poetry, The Visible Man, I was worried it would be narrowly defined by its gay content, but Seamus objected, using the word “arena”—the arena of human emotion, he called it—which is where all good poems must operate, rather than catering to special interests. I didn’t expect this from the son of an Irish cattle dealer.

On another occasion, when I was seeking advice about teaching, I told Seamus I didn’t want to compete against the other poets of my generation for the few desirable positions at American universities. “It would take an almost unnatural purity to succeed without teaching,” he told me, emphasizing that he’d been lucky to find a half-year arrangement, giving him eight months of writing time each year. And when he visited my undergraduate poetry writing class, he told a student who complained about being from Salem, Oregon, where’d she’d grown up in a bookless, media-dominated, environment, that most fine writers were from disadvantaged backgrounds and this, in and of itself, wasn’t an excuse for not succeeding. Of course, it did not surprise me to hear this from a scholarship boy, the eldest of nine children, who’d grown up on a small farm in a country of posted soldiers.

At Pamplona, we ordered espressos, and the shiny stainless steel espresso machine whistled in the background. Steam forced through roasted and powdered coffee beans makes a shrieking sound, like truth and sadness mixed up together at the same time.

A version of this essay originally appeared in Death by Pad Thai: And Other Unforgettable Meals.