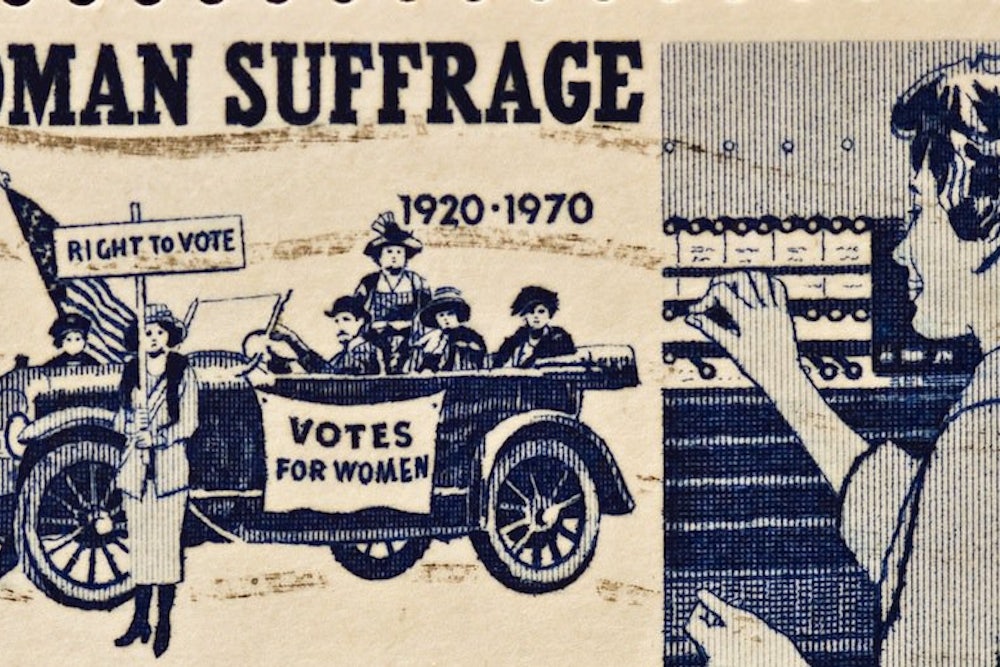

On this day in 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment allowing women the right to vote became part of the United States Constitution. Writing in 1915, Francis Hackett analyzes the politics behind the suffrage movement and the decision to pursue a constitutional amendment to attain the right to vote.

Woman suffragists are lacking in consideration. Having poured out their strength in the fall, they were repulsed in four Eastern states. Under such circumstances they should have subsided. Beaten in New York, New Jersey and Massachusetts by considerable majorities, beaten in Pennsylvania by the inertia of Philadelphia, its unpatched spiritual puncture, it was their plain obligation to stay beaten. But they decline to stay beaten. In spite of their downfall the suffragists persist. In spite of their lavish expenditures, mental and physical, they continue to draw on their resources—resources fed by a purpose so recurrent as to seem unconquerable as naturalness itself. They are neither exhausted nor discouraged. And the very leaders who most spent themselves in unfavorable campaigns now undertake, worn but tireless, the organization of national action.

The terms of that national action have just been defined by two national suffragist conventions at Washington, D. C. Outside suffrage circles those terms remain vague. Inside suffrage circles, because of the divergences of the two conventions, they are not wholly understood. But there is no real reason for the confusion, and the sharper the differentiation the better.

So far as federal legislation is concerned, all the suffragists assembled in Washington met to work toward the same objective. That is the simple equal franchise amendment to the federal constitution, known to suffragists as the Susan B. Anthony amendment Although they agree on this objective, the policies of the two organizations thereafter disagree. The smaller organization, the Congressional Union, specializes entirely on the federal amendment. It elects to disregard the process of ratification state by state so far as immediate action is concerned. It considers federal action on the suffrage amendment the summunt bonum, and it believes in concentrating agitation for suffrage on the party that has power at the moment. For that purpose it believes that all women should judge the government at Washington solely with respect to its attitude toward the suffrage amendment. It believes that women should work with all parties when necessary, but it believes also that in the states where women have the vote, that vote should be used solely for its leverage on the obdurate legislators at Washington. The larger organization, the National Association, has a different policy. And how the Union came to diverge from the National may perhaps be gathered by glancing at the National's history.

At its inception, naturally, the National Association did not concentrate on federal legislation. Itself the result of a union between state and national workers, it sought both types of enfranchisement from the start, but because the Western states offered the line of least resistance the work in the states became paramount. It was, in fact, a necessary preliminary to work on the hill at Washington. The early suffragists were pioneers. They were voices crying in the wilderness. They had in them that obduracy of disinterested principle which nothing on earth can alter, but they were not, like Messrs. Roosevelt and Harriman, "practical men." They presented their Susan B. Anthony amendment without any reference to lobbying—possibly with a shrewd recognition of the inutility of lobbying. But to the cause they were consecrated. It was a righteousness of which they were priests and prophets. The actual fruition of the educational campaigns in the West, however, began to qualify the National's attitude. With the increase in the number of suffrage states, moreover, the prospect for federal amendment changed, and the National came to be more than a centralization for propaganda. It began to be a centralization for federal policy.

At Philadelphia in 1912 the first effort at sustained leverage on Congress was ordained. Miss Jane Addams and others brought about the appointment of a congressional committee to lobby in Washington for the federal amendment. At the head of this committee was placed a young devotee to the cause. Miss Alice Paul, who, like Miss Lucy Burns and Miss Anne Martin, had worked for suffrage with the Pankhursts in England. At Washington, in 1912-1913, Miss Paul and Miss Burns went among the legislators on the hill, and they amplified that work by forming an auxiliary of their commit tee, the Congressional Union. But before the convention of 1913 this offspring of 1912 developed a character by no means anticipated. The Union, in the view of the National, aimed to hold the "party in power" strictly responsible for the passage of the federal amendment. As the National had always proclaimed itself non-partisan this stigmatization of a given party as anti-suffrage was deemed unwarranted. As an appointee of the National, Miss Paul was held to account for this policy in 1913. She declined to abandon it. After much discussion a new capitol committee was nominated by the National, headed by Mrs. Medill McCormick, to conduct lobbying in Washington on non-partisan lines. The National Board then sought to deal with its deposed appointee. But Miss Alice Paul was firmly convinced that her policy at the capitol was the right one. Backed by one of the former contributors to the National, Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont, she decided to extend the Congressional Union as a national organization for the purpose of securing passage of the Susan B. Anthony amendment. As she clung to her policy of discriminating against the party in office, the National refused to affiliate her Union.

Meanwhile the effect of Miss Paul's secession stimulated the National's federal policy. Although convinced by a large majority that it was a great mistake to antagonize any party as such, the National proceeded by means of its workers at congress to organize pressure on individual anti-suffrage congressmen from their home districts. And an attempt at political inventiveness was shown in the formulation of another suffrage amendment, the Shafroth, which aimed to circumvent the state rights objection of the Democratic party.

In 1913-1914 the Congressional Union sought to give effect to its federal policy by opposing the re-election of Democratic congressmen as such. Since it campaigned principally in the equal suffrage states, however, it found itself compelled by its logic to attack some of the ablest and strongest federal advocates of suffrage. It justified this action on the ground that no Democratic congressman had left the party caucus that condemned suffrage, while Democratic congressmen had left the party caucus because of the duty on beet sugar. Beet sugar was more important to Democrats than woman suffrage. In the eyes of Senator Thomas, who had worked night and day for suffrage at the capitol, this opposition was ridiculous, unreasoning and unjust. It was, at any rate, quite dubious in its political effect. Had the Congressional Union marshalled all enfranchised women against the Democratic party, its leaders might have inspired fear and a contrite spirit and a federal amendment. As it was, they caused immense irritation among the partisan women voters in the suffrage states. They seemed political fanatics to pro-suffrage congressmen, and they do not appear to have brought about any incontrovertible defeats. They assert that as a result of their efforts, however, the Democrats at Washington are much more amenable. They indicate that President Wilson voted for suffrage. Whether these results are the outcome of the anti-party policy is a point much in dispute.

At Nashville in 1914, the members of the National were agitated as to the rival claims of their own congressional policy and the Union's congressional policy. For a time a minority hoped that Miss Paul's views might be made to prevail, but the overwhelming majority of the delegates opposed the marshalling of their forces against the party in power. Not in the least deterred by this non-partisan conviction, the Union set itself out to organize national activity, and in 1915 over 150 delegates came to its convention. Of these delegates a fair proportion belong also to the National, and one of the principal objects of these members at the National convention was to deflect the National's party policy. The resignation of Dr. Anna Howard Shaw from the presidency of the National was regarded by some as favoring this possibility. But Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt, the new president, revealed no desire whatever to assimilate the National’s policy to the Union’s. A joint conference between the leaders of these groups produced no result whatever, save a perfunctory asseveration that the capitol committees might consult over their lobbying.

Whether Miss Paul and her associates will succeed in building up a duplicate suffrage organization to work in the states for federal amendment by compulsion is an open question. This, however, is to be said: the Union’s activity marks the evolution of suffrage from propagandism into national politics. And the mere fact that the National Association has put its Shafroth amendment on the shelf proves that lively and bitter criticism has its positive effects.

Whatever the prospects of the Union policy, the prospects of the National policy seem healthy. The suffragists will miss the gallant personality of Dr. Shaw, now retiring after twelve years; but its new Board is of the sort to slave with endless endurance amid the rocks and weeds and wastes of the public as well as the political mind. As an organization of will as distinct from an organization of thought the National bids fair to remain persistent. With Mrs. Catt coming from the New York campaign, Mrs. Roessing and Mrs. Patterson taking office after their labors in Pennsylvania, Miss Ogden after her experience in New Jersey, the body promises to have vigor and inspiration and skill.

With the development of different and divergent methods of advancing the suffrage cause, methods which the leaders at Washington did not reconcile, the movement is now in the throes of actual political experience. The value of this experience will be incalculable. Whether you believe the National Association intolerant, outworn, over-reasonable, or the Congressional Union intransigent, premature, unreasonable, you must recognize in their conflict the very proofs of heightened political consciousness in women. And that, whatever your own choice as to method, whatever your urgent conviction that a choice should be made, is now the salient feature of the movement nationally organized.