You have probably never heard of the young painter Eleanor Ray, but she is a virtuoso, no question about it. She also has a bad case of what I would call the teensies. Frankly, I worry that it may be terminal. Fresh out of graduate school, with a show at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects on the Lower East Side over the winter, Ray brings a tightly controlled painterly panache to her itsy-bitsy glimpses of the view through a window, or some empty shelves, or a bicycle locked to a post. The sizes of the panels on which she paints—one is two and one-quarter inches by two and three-quarters inches and the biggest is five by seven inches—suggest a reverse hubris, a pride in how much she can do with so little. There is something about Ray’s hunkered-down facility that strikes me as symptomatic of a fearfulness that overtakes all too many serious painters today. As much as I worry about the power of the trashmeisters who now dominate so many of our galleries and museums, I worry more about an atmosphere that makes it so difficult for painters who are actually engaged with the possibilities of brushes and pigments to feel free.

Eleanor Ray is in her mid-twenties. That is a time in artists’ lives when they ought to be trying things out, unafraid to make a bad painting. The best artists—the greatest artists—are not afraid to fail. As for Ray, instead of allowing herself to experiment, she remains armored inside her minuscule vignettes. Why this should be I can’t say for sure. But I have a theory. I wonder if Ray, coming of age at a time when painting is said by so many to be dead or dying, believes that the best she can do as a painter is keep a few tiny embers alive. You cannot help but feel a certain respect for her perfectly ordered minuscule vignettes, with their meticulously modulated grays and their knowing allusions to Morandi’s compositional strategies. When Ray paints light reflected off snow or coming through a crack in a door, she goes for a dashing verisimilitude—a sort of painterly déjà vu. The trouble is that the sizes of the paintings are designed to wrap up any unresolved conflicts in a perfect little package. You cannot really access these paintings. They’re so damn small that they feel as if they’re in lockdown. There is a sensibility here, but it is imprisoned. Whatever interesting conflicts and contradictions the subjects might provoke have been squared away without ever really being addressed.

Painting, which for centuries reigned supreme among the visual arts, has fallen from grace. I am quite sure that Eleanor Ray is aware of this. Every serious painter is. Which is not to say that painting is dead, or dying, or even in eclipse: excellent paintings have been done in the last few years, and there are masterpieces that date from the past quarter of a century. But the painter’s basic challenge, the manipulation of colors and forms and metaphors on the flat plane with its almost inevitably rectangular shape, is no longer generally seen as art’s alpha and omega, as the primary place in the visual arts where meaning and mystery are believed to come together. Everybody I know who paints or cares about painting worries about how we are going to respond to this turn of events. Ray is not alone in going into a defensive posture. With her lyrical painterly postcards, she strikes me as too willing to accept the idea that what has vanished in recent years, perhaps never to return, is painting as an expansive and foundational value or idea—as something worth boldly working for. There is no fight in her work. Behind the elegance of her effects, I sense the sadness of defeat. She is much too young for that.

What is to be done? Nothing at all, some would say. Many people who closely follow the visual arts subscribe to a cheerful chaos theory. And judged from such a perspective, anything goes: painting’s fall from grace is an interesting data point, nothing more. But the how and the why of that fall from grace remain to be understood. And understanding what has happened is an urgent matter, not only for the painters whose work still dominates many of the contemporary galleries but also for the gallerygoers and museumgoers who still look to their work. The arrival of a new painter in a blue-chip gallery can even now inspire enthusiasm, as Julie Mehretu’s first solo show at Marian Goodman’s New York gallery did this spring. Brett Baker, a painter who had an incisive and boisterous show of small abstract paintings at Elizabeth Harris this past winter, edits an online magazine called Painters’ Table, which reflects the invigorating range of intellectual conversation still inspired by the painter’s art. Painting’s fall from grace has precipitated quite a few exhibitions dedicated to revisionist and alternative histories of painting, including “Reinventing Abstraction: New York Painting in the 1980s,” organized by the critic Raphael Rubinstein at Cheim & Read in New York over the summer. This show examines the work of fifteen artists, including Carroll Dunham, Bill Jensen, and Joan Snyder, with the goal of rethinking the state of painting in light of transformations in abstraction that began a generation ago. For those who want to look even farther back for promising directions that painters might further explore, there are certainly insights to be gained from an important survey of Richard Diebenkorn’s work from the 1950s and 1960s, currently at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

Ever since the Renaissance, painting has been the grandest intellectual adventure in the visual arts, a titanic effort to encompass the glorious instability and variability of experience within the stability of a sharply delimited two-dimensional space. I think there is no question that the increasing marginalization of painting in recent decades has everything to do with a growing skepticism about even the possibility of stability. This skepticism now dominates thinking in the art schools, art history departments, museums, and international exhibitions where the shape of the artistic future is by and large determined. As every painter knows, of course, a certain amount of skepticism is part and parcel of the creative act, and the grandeur of painting’s stability has everything to do with all the ways in which the artist challenges and complicates that stability. Painting predicates an irrevocable fact—the plane of the canvas or panel on which the artist works—and then challenges that fundamental truth in an endless variety of ways. And that paradoxical situation may bring us to the reason why painting has fallen from grace. To uphold an absolute as well as all the arguments against that absolute, and to entertain both those positions at the same time, is something that our go-with-the-flow culture finds exceedingly uncomfortable.

Painters are aware of the problem. Nearly everybody now agrees that Clement Greenberg’s brief for the irrevocable stability of painting, a brief at once elegantly plainspoken and maddeningly pontifical, paid far too little attention to the varieties of instability that painting can embrace. There is a widespread suspicion that painting’s fall from grace can be blamed on the artists and the critics who conceived of its history in overly exclusionary terms. And so a thousand alternative histories have bloomed. The painter Carroll Dunham—who exhibits his widely praised and darkly comic canvases at Barbara Gladstone and also writes from time to time for Artforum—recently observed that “there are all kinds of parallel or shadow histories of the twentieth century that are constantly being reshuffled and rediscovered.” Who can disagree? You can find Dunham’s comment in a conversation with the painter Mark Greenwold, published in the catalogue of Greenwold’s show at Sperone Westwater in the Bowery this past spring. Greenwold’s show marked something of an apotheosis for an artist who is nothing if not a re-shuffler of histories and has until now mostly been admired by other artists. Greenwold’s paintings are deranged contemporary Boschian soap operas, in which the artist and his family and friends are represented with overgrown heads, crammed into claustrophobic interior spaces. In his recent paintings Greenwold has allowed bits of abstract imagery—what Dunham calls “Martian peacock” elements—to erupt in front of a face or above a person’s head. Greenwold is rejecting what he calls “this kind of sanitized notion that abstraction is on one side and figuration is the other side, and God forbid they should ever mix in art or in anything.”

Although I sometimes enjoy the finicky punctiliousness of Greenwold’s painterly technique, his work ultimately strikes me as sodden and melodramatic—Kafkaesque kitsch. But Greenwold is obviously an immensely intelligent man, and his conversation with Dunham reveals a good deal about how a serious contemporary painter grapples with the conflict between painting’s stability and painting’s instability. Greenwold struggles with what he describes as his training in “Greenbergian modernism.” While his work is loaded with local color, knotty narratives, psychological suggestions, and wacky humor, he comments somewhat confusingly that he is “not interested in, as I said, narrative and all that stuff. So my premise is Greenberg’s.” What I surmise he is trying to say is that he is interested in the construction of a painting as a formal act. In Greenwold’s case, the formal act is informed by a range of concerns that some might label literary. In addition to speaking about other painters, he comments on Philip Roth, the Yiddish theater, and Woody Allen’s roles in the movies he directs. He obviously admires Allen’s ability to do double-duty as director and actor. Greenwold similarly likes to take a starring part in his own compositions, with his round, bearded, bespectacled head and (often) buck-naked body front and center in his crazed conversation pieces. That Greenwold wants to present life as a freak show does not strike me as strange, not at all, but he fails to integrate the dissonant elements into a convincing whole.

This brings us to the crux of the problem. What is a stable whole that sufficiently acknowledges painting’s life-giving instability? That is the question that preoccupies painters today. And it comes as no surprise that Carroll Dunham, who obviously relishes his conversation with Greenwold, appears as one of the protagonists in the critic Raphael Rubinstein’s exhibition exploring the varieties of instability that nourish recent abstract painting. Looking back to what more than a dozen abstract artists were doing in the 1980s, Rubinstein discovers something rather like Dunham’s “parallel or shadow histories”—what Rubinstein calls “an alternative genealogy for contemporary painting.” Seen at Cheim & Read, “Reinventing Abstraction” certainly has its pleasures. These include Dunham’s elegantly eccentric Horizontal Bands (1982–1983), the cool formal title giving no hint as to the jam-up of witty, bulbous, bulb-and-root forms; Joan Snyder’s rapturous lyric pastoral Beanfield With Music (1984), with its luxuriantly orchestrated cacophony of greens; and Bill Jensen’s The Tempest (1980–1981), a floating enigma like an astral starfish with a sci-fi snout, at once melancholy and oracular. The other artists in the show are Louise Fishman, Mary Heilmann, Jonathan Lasker, Stephen Mueller, Elizabeth Murray, Thomas Nozkowski, David Reed, Pat Steir, Gary Stephan, Stanley Whitney, Jack Whitten, and Terry Winters.

Rubinstein wants to move beyond the shopworn talk about the death of painting or the return of painting to “the urgent task of building a bridge from the radical, deconstructive abstraction of the late 1960s and 1970s (which many of [the artists in the show] had been marked by) toward a larger painting history and more subjective approaches.” What Rubinstein is arguing for is the polar opposite of Eliot’s impersonal view of the past in “Tradition and the Individual Talent”—the “larger painting history” he advocates is nourished by a wide range of highly personal, subjective approaches. The fact that the works included in “Reinventing Abstraction” look very different from one another is precisely the point. If the artists are joined in their taste for heterogeneity, that taste also divides them, for each is heterogeneous in his or her own way. We find here more or less painterly ways of painting, experiments with a range of flat and relatively deep spaces, and the incorporation of elements ranging from nearly naturalistic to thoroughly nonobjective. If I understand Rubinstein correctly, he wants to rediscover avenues in recent artistic tradition too little seen or understood, and in so doing to excavate routes from the more distant past to the present.

I am sympathetic with Rubinstein’s project. Certainly you can make a strong case that the history of painting consists of nothing more than the individual histories of painters. But as Rubinstein is also well aware, the history of painting must ultimately be something more than an anthology of individual histories. If the danger of a totally integrated history of painting is that it degenerates into a frozen academicism, the danger of a thousand individual histories is that painting becomes no more than another competitor in the bazaar that is contemporary art, a take-it-or-leave-it proposition, with no more claim on our attention than anything else.

One would hope that some more general principle could be derived from the personal histories that rivet us. It is precisely the possibility of discovering the general within the particular that drew me to San Francisco, for a major exhibition at the de Young Museum of the work that Richard Diebenkorn did as a relatively young man in the 1950s and 1960s. “Richard Diebenkorn: The Berkeley Years: 1953–1966” was organized by Timothy Anglin Burgard, a curator at the de Young (which is part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco); the exhibition goes to the Palm Springs Art Museum in the fall. While everybody knows that Diebenkorn painted his figures, still lifes, and landscapes under the impact of Matisse, the lessons that he drew from Matisse are far richer and more paradoxical than has generally been acknowledged. Diebenkorn cuts straight through the reductive formal strategies that are all too often said to be Matisse’s central gift to twentieth-century art, and recovers Matisse’s concern with the painting as symbolist experience.

Beginning with the abstract landscapes of the early 1950s, Diebenkorn refuses to allow his paintings to make sense either in purely naturalistic or purely abstract terms. He walks a tightrope in his figures and landscapes of the late 1950s and early 1960s—the best work he ever did—as he moves from passages of almost atmospheric tonal color to strident arrangements of full-strength red, orange, purple, yellow, green, and blue. He convinces me that it is the force of his feelings that precipitates his hyperbolic colors and forms. And his feelings seem to keep changing, even within a single painting, so that sometimes a woman’s arm is a woman’s arm and a wedge of sky is a wedge of sky, and sometimes a woman’s arm is a dead weight and a wedge of sky is an abyss.

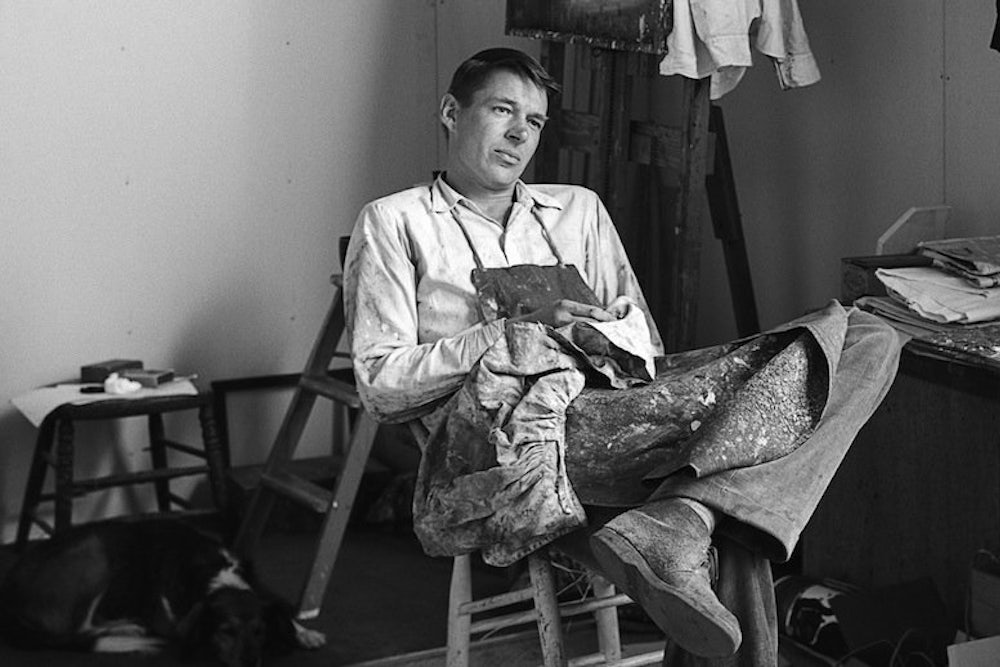

Particularly fascinating is the relationship between Diebenkorn’s paintings and the considerable number of drawings in the de Young show, especially of female figures clothed and nude. Although most of the drawings included date from after the preponderance of the figure paintings were done in the late 1950s, a photograph of Diebenkorn at a drawing session in 1956 and another photograph, this one by Hans Namuth, of Diebenkorn drawing his wife in 1958 make it clear that drawing and painting proceeded at least on parallel tracks. Diebenkorn’s drawings of women, whether still quite young or on the cusp of middle age, reveal a considerable range of emotions: sexual charm and challenge are mingled with anguish, anxiety, and ennui. With their casual haircuts, unselfconscious glances, and long, sexy legs, these women suggest all the tensions and roiling excitement of the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the Eisenhower years were ending and ambitions erotic and otherwise were increasingly openly expressed. (The only other artist whose drawings of that time suggest such a grown-up feeling for male-female relations is R. B. Kitaj, and the two painters became friends when Kitaj spent time in California in the 1960s.) If Diebenkorn always regarded drawing and painting as separate activities—and is generally more of a naturalist on paper than on canvas—we can also see how the psychological crosscurrents in the drawings are enlarged and in a way allegorized in the paintings, where the increasingly abstract use of color and shape take on an emblematic power.

I have heard it said by some painters that Diebenkorn was unable to place his figures in a legible three-dimensional space. But he was perfectly capable of doing so in the drawings—so who can doubt that when he turned to painting he wanted to do something rather different? In Woman on a Porch (1958), one of the finest of the paintings in which figure and landscape are joined or juxtaposed, we do not know that the woman is on a porch, and that is probably what Diebenkorn intended. The figure, seated in what looks like a wicker chair, seen from the knees up, her head downward cast, is set against a landscape of strong horizontal forms. The color is extravagant, maybe gaudy, with oranges that verge on the lurid and with blackish, purplish blues. The woman’s body, solid and sensual, is monumentalized. She is a totem, an icon, a pure contemplative power merging with the blocky forms of the landscape, a human puzzle knit into the puzzle of the landscape. Although certainly not abstract, the painting is also not exactly representational, certainly not a representation of reality. The landscape’s strong colors and enigmatically simplified forms become emblematic of the woman’s state of mind. What does she feel? The answer is to be discovered in how the colors and forms feel. And if that is difficult to determine—well, aren’t a person’s feelings often difficult to explain?

In the late 1950s, Diebenkorn said that “all paintings start out of a mood, out of a relationship with things or people, out of a complete visual impression. To call this expression abstract seems to me often to confuse the issue.” Diebenkorn is associating himself with a tradition that I would characterize in the broadest sense as symbolist. The enigma of human consciousness is revealed indirectly, through a pictorial environment in which naturalistic perceptions have been transformed by the myriad processes and pressures of the imagination. The frame of a window becomes a prison. The blue of the horizon becomes a promise. Diebenkorn’s figures are a considerable contribution to a modern symbolist tradition that includes Redon’s phantasmagorical portraits, Vuillard’s luxuriantly perfervid interiors, Matisse’s studies of Madame Matisse crowned by extraordinary hats, and Bonnard’s climactic painting of his wife in the bathtub, in which the white tile walls explode in a riot of ardent color.

Considering how unwilling Diebenkorn was to retreat to the safety of a format or a formula in the 1950s and early 1960s, it is thrilling to realize how many good and maybe even great paintings there are. Santa Cruz I (1962), a view of ocean and ocean-side buildings, is as convincing a portrait of the California coastline as I know, a worthy successor to Matisse’s views of the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. Some tiny still lifes done in 1963—a knife in a glass of water, a knife cutting through a tomato—are in the tradition of Manet’s quick little compositions and may well be superior to them in their firm architecture and unsentimental lucidity. There are some extraordinary interiors in which a human presence is suggested with haunting circumspection by means of a painting of a woman’s head leaning against a wall or a group of figure drawings pinned to the studio wall. Diebenkorn’s restlessness is one of the fascinations of midcentury art, as he moves from the almost crude figural style of Coffee (1959) to the Ingresque sensuality of Sleeping Woman (1961). Diebenkorn is of course hardly alone in the directions he took in those years. On the East Coast quite a few artists who had emerged amid the culture of abstraction were evolving original figurative styles, among them Fairfield Porter and Louisa Matthiasdottir—but Diebenkorn may be the only artist who at least for a time managed to impose so insistently abstract and symbolic an imagination on the figure and the landscape without yielding to simplistic solutions.

Diebenkorn’s figures, landscapes, and still lifes from the late 1950s and early 1960s are a reminder of how much instability must be encompassed within the stability of a painting. As for the Ocean Park series that preoccupied Diebenkorn as he grew older (he died in 1993), I wonder if the more formalized and regularized abstract processes involved in those paintings did not reflect the worries of an artist who had once upon a time put stability at such considerable risk. I would not want to press too hard on a psychological interpretation of Diebenkorn’s development. Suffice it to say that the conundrum for painters in the past several decades has been how to maintain some dependable conception of what painting is all about while insisting on the freedom of action needed to keep that concept alive. To do so successfully involves quite a juggling act. In the past couple of years I have sensed in the work of painters who hold a particular interest for significant numbers of other painters—they include John Dubrow, Bill Jensen, Joan Snyder, and Thornton Willis—the sobering challenges involved in maintaining both some reliable standard and the freedom to take fresh risks. There is always the necessity to hold the line even as one goes over the line, to maintain some sense of what painting is before all else in the face of an environment in which anything goes.

The evolution of painting is inevitably as much a matter of repetition as it is a matter of change. But what is too little change and what is too much? As Rubinstein observes in the catalogue of “Reinventing Abstraction,” it is significant that after all the talk in the 1960s and 1970s of the shaped canvas and the end of the tyranny of the rectangle, the artists in his show—with the exception of Elizabeth Murray—have found themselves loyal to the framing rectangle. With painting, we recognize the excitement of the new not so much through its distance from earlier work as in the extent to which the old ways are given some new sting or attack or power. The wide panoramic abstractions in Julie Mehretu’s show at Marian Goodman this spring, with their layering of architectural elements and their dramatically deep space, put me in mind of Al Held’s later work, which also had a cinematic and even a sci-fi quality. And that connection interested me, reviving as it did unresolved feelings I have always had about Held’s pictorial dramaturgy. As for the lush, thickly applied color in Brett Baker’s small abstractions, at Elizabeth Harris over the winter, they brought to mind Paul Klee’s Magic Squares and the weavings of Anni Albers and Sheila Hicks—the question became how Baker’s own feeling for sensuous coloristic hedonism is strengthened and deepened by the restraining power of a grid. The beauty of painting is that we experience the individualism of the painter but never exactly in isolation. The painter is always simultaneously in the community of painters, of the present and of the past.

To assert that painting is a great tradition is to assert the obvious. Nobody would disagree, even those who take no interest whatsoever in contemporary painting. The problem for contemporary painters begins with the collapse of the framing rectangle as the artist’s essential way of experiencing the world. I am not sure to what degree the stabilizing supremacy of that rectangle has been undermined by the technology that surrounds us, whether the layered space of the computer screen, the roving eye of the digital camera, or the increasing ubiquity of 3-D movies. But even if the rectangle remains essential, its centrality unexpectedly reaffirmed by the shape of the iPad and the iPhone, there is no question that we are increasingly encouraged to regard continuous visual flux as the fundamental artistic experience. When the Dadaists in the 1920s and even the postmodernists in the 1970s and 1980s turned their backs on painting, they tended to assume that it was still there, behind them, a stable fact. Now painting itself is frequently seen as simply another dissident form, a way of turning one’s back on moving images or performance art or assemblage. All too often today, when painters walk out of their studios, they find themselves in a defensive posture or an offensive one, with painting their shield or their battering ram. The trouble is that you cannot really get down to the business of painting when you are forced into either a defensive or an offensive pose.

The great question now is how to preserve and even honor the age-old stability of painting without falling into the trap of a frozen academicism. Richard Diebenkorn, in his figure and landscape paintings of the late 1950s and early 1960s, suggests a provocative balance, one worth reinvestigating. The bottom line is that each artist must now begin pretty much from scratch, obliged to develop both a personal conservatism and a personal radicalism. This is the painter’s predicament.

Jed Perl is the art critic for The New Republic and the author, most recently, of Magicians and Charlatans (Eakins Press Foundation).