For years, Alfred Hitchcock was written off as “the master of suspense,” and now the late Sir Alfred has been similarly eulogized. The epithet is rich with slighting implications. It suggests, first of all, that Hitchcock was stuck in a rut, playing with kid stuff: he made “thrillers” (as John Ford made “Westerns”), while Welles and Bergman created films. “Master of suspense” also connotes the technician’s narrow expertise. Knowing all the tricks of the trade, that “master” could work his audience adroitly. Such a talent seems manipulative as well as limited; a “master of suspense” is, literally, a puppeteer.

Of course the epithet has always been used with affection by those well-meaning triflers who call themselves “film buffs.” These people like to memorize “great touches,” “classic scenes,” the clips that fill out TV specials: Cary Grant on his way upstairs with the Fatal Glass of Milk, Cary Grant running away from the crop-dusting plane, Gary Grant on his way downstairs with Ingrid Bergman, Janet Leigh taking her shower. By celebrating only a few thrills, these enthusiasts perpetuate the notion that Hitchcock was simply a gifted sensationalist, which is just what his detractors like to claim: “a dealer in shock, as another might go in for dry goods” (Dwight MacDonald), “a pop cynic, cinematically ingenious” (Stanley Kauffmann), “a masterly builder of mousetraps,” whose techniques “have more to do with gamesmanship than with art” (Pauline Kael), etc. He has been both dismissed and idolized for the same wrong reason. His fans and his critics implicitly agree that Alfred Hitchcock will loom large in the annals of mass titillation, along with PT Barnum, Josef Goebbels, and the roller coaster.

Hitchcock himself inadvertently helped to foster this impression. Although voluble in interviews, he shied away from exegesis. He would hastily explain things in the simplest terms, or frustrate questions of interpretation with genial acquiescence. Asked if a certain scene might have this or that significance, Hitchcock would agree that it was possible, and the subject would be closed: “Isn’t it a fascinating design? One could study it forever.” Rather than play the critic, he would tell anecdotes, formulate rules on narrative strategy, and boast about his technical inventions: “By the way, did you like the scene with the glass of milk?” he asked Truffaut: “I put a light right inside the glass because I wanted it to be luminous.” He would pretend not to have thought about the most important things, dwelling instead on how he got the glass to glow, the merry-go-round to run wild, the plane to crash at sea.

This apparent fascination with mechanics sometimes was taken as proof that Hitchcock was only after neat effects and crude responses. In fact, the opposite is true. He considered those effects amusing, but not all that important since he seemed downright eager to spoil their impact by carefully explaining them. (Even while The Birds was still in production, he was already telling interviewers how he managed the illusion of a bird attack.) Moreover, by talking mostly about the nuts and bolts of spectacle, Hitchcock could avoid making authorial pronouncements that might have limited the meanings of his films. He would not struggle to describe what he wanted his viewers to see for themselves.

This was his implicit purpose, and the secret of his inexhaustible cinema: he wanted his viewers to learn for themselves how to see for themselves. He would have us discover our vision, and then distrust it. “You expect quite a lot of your audience,” suggested one interviewer. “For those who want it,” he replied: “I don’t think films should be looked at once.” “For those who want it”: although Hitchcock was adept at providing his one-shot viewers with a good 90-minute jolt, he was uneasy about so mechanical an exercise, and worked, ever more subtly, to draw the viewer toward an awareness of visual nuance that would surpass the immediate pleasures of the one-night stand. And he could do this because he had mastered every aspect of his art.

He was a great screenwriter. Although he took a writer’s credit only once after 1932 (for Dial M for Murder), his was the guiding intelligence behind nearly all his scripts, and “quite a bit” (he said) of the actual dialogue was his own: “You see I used to be a writer myself years ago,” he once remarked, with his usual nonchalance. His narrative abilities, his sense of plot and pacing, remain unequaled. Moreover, he had a genius for colloquialism. Although largely noted for some macabre double entendres (“Mother— what is the phrase?—isn’t quite herself today”), Hitchcock’s dialogue is, in fact, exemplary in every way—witty, succinct, evocative, and full of meaning, as simple conversations, “innocent remarks,” work tellingly against the visual event. This kind of irony depends on several gifts: Hitchcock was as skillful a dramatic poet as a metteur-en-scene. He would claim not to care about the wording of the lines, but his deft scripts and careful working habits belie this pretense of indifference. He approached his writers not as taskmaster, but as a scrupulous collaborator, able to draw the best from Charles Bennett, Ernest Lehman, Thornton Wilder, Evan Hunter, John Michael Hayes, and many others, including his wife. Alma Reville, who was his right hand from 1922 until the end.

He also worked effectively with actors, inspiring dozens of the most memorable portrayals in cinema, and countless vivid bits from hundreds of supporting players. We are often told that his actors merely posed for the camera, but that judgment is absurd. Hitchcock’s dramas of ambivalence demanded that his actors project the most complex of characterizations: Teresa Wright’s Charlie, passing from blitheness into uneasy resignation in Shadow of a Doubt; Claude Rains’s Alex Sebastien in Notorious, charming and miserable, then savagely resentful, and, in the same film, Ingrid Bergman as Alicia Huberman, as reckless in rejection as in love; Herbert Marshall’s guilt-ridden ironist in Foreign Correspondent; Oscar Homolka’s petit bourgeois subversive, sly and thoughtless, in Sabotage; Jessica Tandy as Mrs. Brenner in The Birds, struggling to preserve her household and her sanity; and many more, including Hitchcock’s three great monsters: Joseph Cotten as Uncle Charlie, the dapper nihilist in Shadow of a Doubt, Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train, as the feline and dissipated Bruno Anthony, and, in Psycho, Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates, the boyish mass murderer and malaprop. Hitchcock displayed Cary Grant’s great flexibility in Notorious, Suspicion, North by Northwest, and To Catch a Thief, showed something of James Stewart’s range in Rear Window, Vertigo, Rope, and the remake of The Man Who Knew Too Much, and proved that Grace Kelly was more than just a chilly face.

“I have never worked with anyone who was more considerate, more helpful, more understanding of actors than Hitchcock,” says James Stewart, who ought to know, and Ingrid Bergman once suggested that “every actor who has ever worked with Hitchcock would like to work with him again.” There were a few who might have disagreed. Because he never improvised and liked to do things amicably, Hitchcock did not work well with temperamental types (Charles Laughton in Jamaica Inn, Kim Novak in Vertigo), and was impatient with those Method actors (Montgomery Clift in Confess, Paul Newman in Torn Curtain) who asked a lot of questions. Nevertheless, his experience with actors was, by and large, a happy one, as those two tributes and many fine performances attest. That celebrated crack about actors and cattle had nothing to do with Hitchcock’s practice (and is, moreover, untraceable, although Hitchcock liked to provoke people by repeating it).

It was, above all, in his use of technique that Hitchcock most obviously surpassed his peers and guided his successors. The buffs are too restrained in their praises. Since by “technique” they actually mean “ingenious bits,” their little list of Hitchcock’s great effects—shower, crop-duster, glass of milk—is much too short. Those better-known moments represent only a handful of Hitchcock’s many master strokes: in Blackmail, a chase through the British Museum, all done with mirrors in the studio; in Spellbound, a shot, from the suicidal gunman’s point of view, of a hand holding a pistol, which slowly turns and fires into the camera (“I wound up using a giant hand,” Hitchcock explained, “and a gun four times the natural size”); the dizzying subjective shot in Vertigo; the “score” of The Birds, all electronic sound effects (even the climactic “silence”); the dolly back down the stairs and out into the street in Frenzy; and so on. As a craftsman, Hitchcock was, indeed, unparalleled, so well acquainted with his tools that he never had to look into the camera, because he always knew how any given shot would come out.

Technique, however, involves much than virtuosity. The buffs not only ignore most of Hitchcock’s technical feats, but further belittle his achievement by extolling those feats only as triumphs of engineering: they marvel that he could work his gadgets and his audience with equal dexterity, thus praising his films as just the kind of empty tours de force we would expect from a “master of suspense.” But why, if Hitchcock was such a skillful manipulator, were his attempts at drum-beating (Lifeboat, Saboteur, Foreign Correspondent) too equivocal to do the job? A “master of suspense” ought to have excelled at propaganda, along with Ford and Capra, but Hitchcock’s vision was not unambiguous enough. And why did Hitchcock insist that “most films should be seen through more than once,” if all he wanted from his viewers was a certain number of shrieks and shudders? Did Hitchcock ever rely on gimmickry, or use his technique as a behaviorist might use electrodes? On the contrary, that technique, while always startling, was always more than that: “I am against virtuosity for its own sake,” he told Truffaut: “Technique should enrich the action.” That dictum was the fruit of long experience. The more carefully we study Hitchcock’s technique, the more exciting it becomes, for it is always apt, suggestive, multiply significant, its images meticulously conceived and conjoined. It is, in short, the work of a man who ought simply to be honored as “the Master.”

How, then, do we explode that other epithet? We might consider the other modes that Hitchcock had “mastered,” and point out that he was also adept at comedy, and that he had a fine eye for the glow and shadows of romance, and that he was an able satirist. Lists, however, are no more useful than labels. Anyone can simply catalogue an artist’s capabilities (as I have been doing here), but that is the sport of buffs and columnists: Hitchcock’s genius demands a more expansive kind of appraisal, which film criticism is not ready to yield. No easy categories can do him justice, just as his would-be mimics have missed the point. His style, supposedly all lurid tricks and broad contrivances, has proved inimitable. Among the dozens of hommages and parodies—attempts by Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Stanley Donen, Mel Brooks, Brian de Palma, and others—not one successfully evokes the source. No other director has been able to attain the peculiar intensity, the mood of ambiguous discovery, that gives Hitchcock’s films an emotional power which only increases with familiarity.

Hitchcock sustained this power through half a century because he never lost his thorough understanding of the viewer: “I always take the audience into account,” he insisted, expressing something subtler than the cunning of a seasoned showman. He never condescended to his audience, never failed to honor their presence, and yet he never trusted them. He felt this deep ambivalence almost from the start of his career, at which time it was something new. Earlier filmmakers, such as Porter, Griffith, Murnau, and Eisenstein, had expected to uplift their eager viewers, hoping that film would put an end to war and ignorance. As a young viewer, then as an apprentice screenwriter and art director, and finally as a director, Hitchcock saw that film had different, more sinister, effects.

Once inside the theater, individuals would melt into a wide-eyed herd. Film brought out the worst in those huddled spectators, who now could enjoy, vicariously, the vices they would ordinarily denounce. Moreover, they were fickle as well as hypocritical and timid, taking sides according to the filmmaker’s whim. Deft editing could overwhelm all ethical distinctions. If a character was nice-looking and endangered, the audience automatically would take his side: show a dashing burglar on the job, then cut to someone coming to surprise him, and suddenly the thief becomes heroic.

Since the viewers put their faith in visual conventions, moreover, “goodness” and “evil” were simply the impressions made by angle, lighting, setting, composition. The viewer would cherish the bright smile in the sunny doorway, condemn the half-lit scowl around the corner. He was, it turned out, no earnest pupil, ripe for betterment, but a thoughtless bigot, making facile judgments in the dark.

Whereas men like Griffith and Eisenstein saw themselves as the custodians of a beneficent new force, Hitchcock distrusted the new medium, with its coercive images and credulous crowds. The process of spectacle—plays, concerts, circuses, games, court trials, public speeches—always is charged with menace in his films: gunmen take aim from theater boxes, murderers try to disappear into their roles, with audiences watching. Film seems especially dangerous in Hitchcock’s films. In Saboteur, a comic shoot-out in a movie coincides with (and conceals) a real shoot-out in the movie theater, and in Sabotage a little boy rides a bus, carrying a time bomb (unwittingly) and two reels of film. The explosion kills every passenger. The film ends with the explosion of a movie theater.

The uneasiness implicit in these sequences led Hitchcock to perfect a brilliant adversary style. While apparently gratifying the viewer’s wish for adventure and “suspense,” Hitchcock actually encourages the viewer to go beyond these vivid first impressions. Unlike his predecessors, who strained to have us see the simple truth, Hitchcock would have us see ourselves straining to see. He never allowed his audience the somnolent comforts of the dark, the soft chair, the warm buttered popcorn, but blocked that sweet escape with troubling reminders of the viewer’s habits and desires. His films seem to point back at us, and our presence and shortsightedness become a part of the story on the screen.

A famous sequence in The Thirty-Nine Steps provides a good example. The film begins with a legend on a marquee: “MUSIC HALL,” the words lighting up, one letter at a time, to the rhythm of a merry overture. An anonymous figure appears at the ticket booth (“Stalls, please”), then inside, handing his ticket to the usher, then taking his seat: Richard Hannay (Robert Donat), a visitor from Canada, and, so far, no more remarkable than any other spectator in his (or our) midst. He watches the performance of Mr. Memory, an expert at recalling trivia, and offers, as a colorless viewer, a colorless question (“How far is Winnipeg from Montreal?”). A few minutes later a brawl breaks out, someone fires a pistol, and in the stampede for the exits Hannay finds himself embracing a frightened woman (Lucie Mannheim) who, once outside, asks him to take her home.

She behaves mysteriously upon entering his flat, avoiding the windows, asking that he turn out the lights, ignore the phone, turn his mirror to the wall. They go into the kitchen for a late supper. As Hannay, still wearing his heavy overcoat, cuts the bread and fries the haddock, “Miss Smith” sits at the table, seductively casual, slowly removing her gloves. She claims to be a spy on a mission, and says that there are two men lingering across the street, waiting to kill her. Hannay sees the men through the window, but responds coldly to her exotic story, muttering about “persecution mania” and keeping on that overcoat, as if fearing for his virtue; “You’re welcome to my bed,” he says, adding that he’ll sleep out on the couch.

Late in the night, “Miss Smith” staggers into the room where Hannay lies sleeping: “Clear out—Hannay! Or they’ll get you too!” She waves a piece of paper toward him, then throws her head back, chokes melodramatically, and falls. So far Hannay, sitting up on the couch, watches this unexpected death scene at a protective distance: Hitchcock shoots the woman’s final agony as if it were a floor show, with Hannay as detached as any audience, his prostrate form defining the lower border of the frame, and his face turned toward the spectacle, away from us, as if he were someone sitting one seat ahead. But now Hannay’s career as a spectator comes to an end. The woman falls startlingly across his lap, like a ballerina diving into the front row; and with the shock of this transgression comes the shocking revelation of a huge knife stuck in the woman’s back.

Although we and Hannay see it simultaneously, Hannay ceases merely to watch. In looking down at the knife, he turns his face toward the camera, thereby giving up the viewer’s sheltering anonymity and taking on the burdens of the actor. He is now vulnerable (shown for the first time without his overcoat), thrust into the very action which he had denied, and oddly guilty: Hitchcock cuts to a close-up of the telephone as it begins to ring again, then to a shot of Hannay backing toward the window, wiping his hands while staring uneasily off at the dead woman, exactly as if he himself had murdered her. The conjunction suggests that Hannay has discovered something fearful within himself: he is no innocent bystander, but capable of murder, like the men outside, or capable of being murdered, like the dead woman before him. He now assumes her obligations and her furtiveness, as if to acknowledge this realization.

The sequence is charged with more significance than can be fully treated here, but we ought to note this crucial strategy: Hannay at first regards his world as if he were not part of it, that is, just as we regard the film; and he can only become effective once he is surprised out of this attitude. Thus Hitchcock’s main characters often first appear as emissaries from the realm of viewers. Carefully dressed and too sure of themselves, each apprehends his world like a bored spectator, killing time until the house lights come up. They presume themselves superior to what they watch; and we share that assumption, until coming to perceive the deeper resemblance between “hero” and “villain,” the interdependence of “good” and “bad,” and, by extension, the disturbing bonds between ourselves and those characters who had at first seemed evil, mad, ridiculous. Many of Hitchcock’s strongest sequences are centered on a shot of recognition, in which some blithe viewer suddenly discerns himself: these shots become more powerful with time, the more we see them not as quick portraits of some “reaction” necessary to the plot, but as reflections.

Each of Hitchcock’s masterpieces reflects upon its viewers differently. Suspicion plays on the distortions of subjective vision, showing how “suspicion” can imbue neutral images with a sense of menace: Lina suspects that her easygoing Johnnie is a murderer at heart, but only because Lina’s heart is full of murder. In Shadow of a Doubt, Satanic Uncle Charlie descends upon his sister’s family in Santa Rosa, and threatens Charlie, his adoring niece, with disillusionment and death. This looks like a confrontation between good and evil, until we realize that the girl’s goodness is merely our invention: in fact, she has called her uncle forth, and finds herself endangered by their similarity.

In Notorious, Alicia Huberman is repeatedly misjudged by Devlin and Sebastien, but the imperceptiveness of these two men is only a reflection of our own: Alicia is “notorious” because of us, the staring multitudes that take mean pleasure in a scandal. Psycho is unfailingly horrific because it suggests a deep complicity between Norman and his victims, between Norman and his viewers. And there are many more—The Lodger, Sabotage, The Secret Agent, Strangers on a Train, Vertigo, North by Northwest, The Birds, and others—whose subtleties demand repeated viewings, whose meanings have been overlooked in the general dismissal of “the master of suspense.”

These films contain more excellence than a single eulogy can honor; and, until they become the subject of intensive criticism, Hitchcock’s place in history will remain unappreciated. He may have been the most accomplished of modernists (“The fact is I practice absurdity quite religiously!”). As early as the 1920s, he was already working cleverly in the self-reflexive mode, and continued to do so with increasing sophistication: North by Northwest, for example, is a modernist masterpiece, centered on nothing at all, and repeatedly referring to itself with an inventiveness and wit unknown in our graduate seminars on literary theory. At the same time, Hitchcock’s films display an exquisite sense of psychological nuance. They may be the most compelling works of this Freudian era, continually sifting “normal behavior” for its ambiguities and unspoken motives. Hitchcock may have presented more of the unconscious life than any other modern artist, from the telling quirks of everyday experience to the terrifying spells of madness. And Hitchcock’s films are profoundly political. His stories of “ordinary people in bizarre situations” contain a vision as appalling as it is familiar: all of a sudden, determined agents come looking for the wrong man. This chilling situation conveys something of the panic that we sense in novels like The Trial, Darkness at Noon, and 1984. But even more politically significant is Hitchcock’s relentless method, available only to the filmmaker: his works encourage us to see anew, to purge our vision of official images and easy preconception. Surrounded by television, we may need Hitchcock’s guidance more than ever.

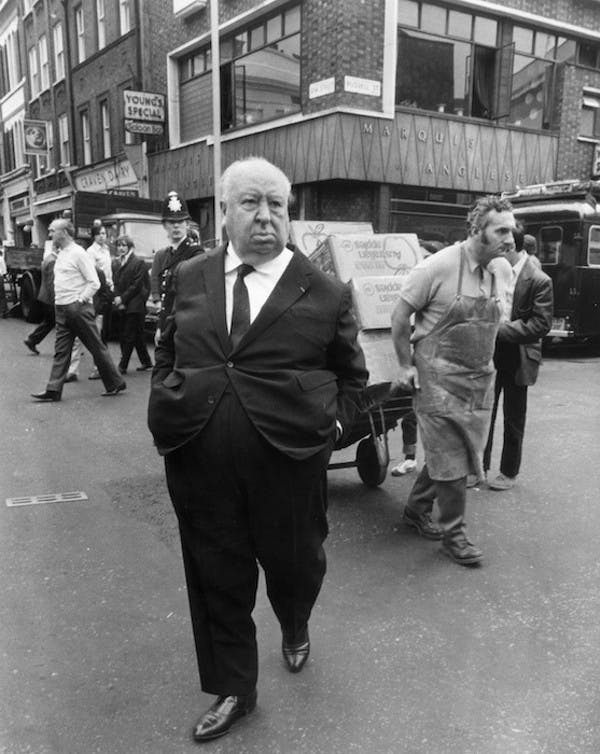

As long as we accept the current trend, however, we will continue to miss the significance of his films and of film in general. Hitchcock’s low repute among reviewers tells us something about the current state of film criticism, and also suggests that the Romantic myth of the artist is still confusing millions. If Hitchcock had been a haunted outcast, throwing up at fancy dinners and dying of cirrhosis in his 40s, the reviewers would be calling him a genius. This myth is especially comforting to journalists. The success of Hollywood’s great professionals—Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks—tends to rankle many reviewers, who would rather not be reminded that their judgments have no public effect whatsoever, and who therefore prefer directors who seem to need as many champions as possible: foreigners with slight domestic appeal and self-destructive or erratic types like Orson Welles and Erich von Stroheim. Many critics fail to hide a twinge of satisfaction when lamenting these abortive careers. Hitchcock, on the other hand, was too wry, too successful, too round to be hailed as a serious artist. He seemed, in fact, to use his public image to contradict that myth deliberately: with his pear shape, his sober clothes, his profile with its mock-hauteur, he looked like an Edwardian greengrocer. His detractors missed the joke, taking it as evidence that Hitchcock lacked imagination, like any other stolid burgher.

That judgment was based on the most superficial of impressions, like all those glib celebrations and dismissals of his work. His great career should now be reconsidered. To refer to Alfred Hitchcock as “the master of suspense” makes as much sense as calling J.M.W. Turner “the seascape whiz,” or calling James Joyce an “ace punster.” He was the greatest of filmmakers, and among the greatest artists of this century. No other director has made films at once so popular and so profound; no other modern artist has moved so many different audiences for so long. For over 50 years, he tried to tease the viewer awake with films of astonishing complexity and power. Now that he is dead, we ought to look at them again.