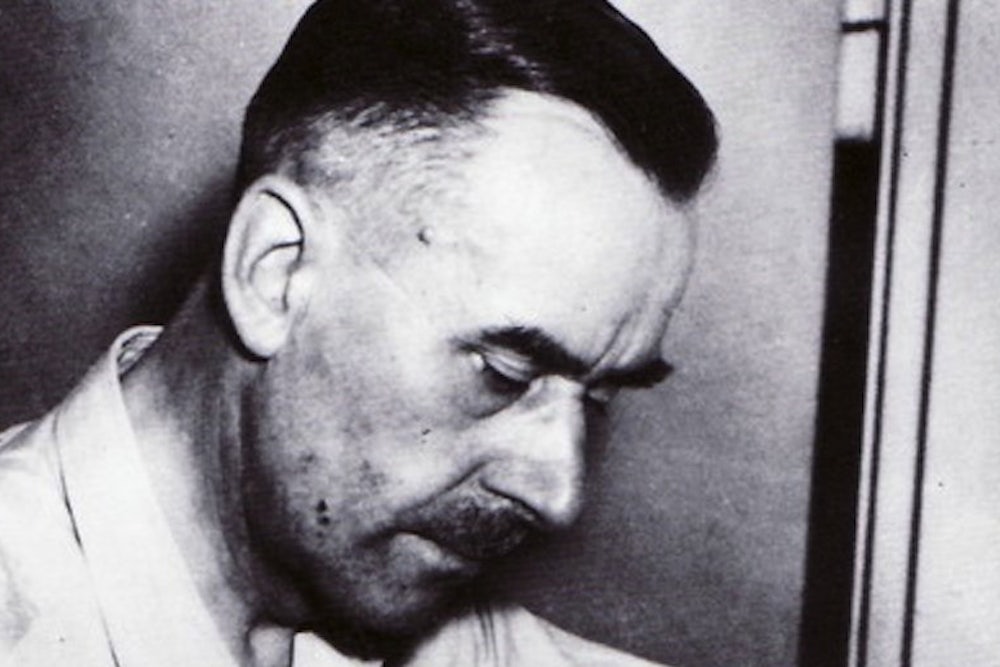

In 1936, Thomas Mann finally broke his silence on a new, Nazi Germany. Here, on the 58th anniversary of Mann's passing, The New Republic editors' original statement in support of his bold choice.

It is news in the international republic of letters when Thomas Mann comes out in opposition to the new Germany. For three years now he has been living in Switzerland, in self-imposed exile, at the cost of sacrificing two-thirds of his personal fortune to the German government. But he has said absolutely nothing about politics, and he did not attend the Writers' Congress for the Defense of Culture, even though his brother Heinrich took a leading part in It. Since Thomas Mann is easily the most distinguished German of letters, and since he is probably more esteemed by writers all over the world than any other living novelist, he has been under pressure from both sides. The Nazis have begged him please to come home and have broadly hinted that his incomprehensible ideas about liberty would be overlooked if he only would say a kind word for the Leader. The anti-fascists have insisted that he join them and have abused him for not cutting the last ties that bound him to Hitler's empire—especially since everybody has known that he hates oppression and abhors anti-Semitism. But it seems to us that his silence has been easy to understand and excuse. It has so far enabled him to keep his German audience; and Mann is a great enough writer to understand that in his audience lies part of his greatness—that without a united body of readers he might become as voiceless and sterile as most of the White Russian novelists who have left the homeland.

Now at last he has broken his long silence, evidently deciding that the truth was more important than his literary career. The immediate occasion was an article printed in Switzerland by Dr. Korrodi, the literary critic of Die Neue Zuricher Zeitung. Korrodi attacked the German writers living in exile—they were for the most part novelists, he said, the good poets and essayists having stayed at home; and they represented the international Jewish influence in German letters, which the fatherland could easily dispense with. Mann came to the defense of his fellow exiles. He did not accuse Korrodi of anti-Semitism, even though the charge would be easy to justify. Mann has the high and now seldom encountered liberal virtue of elevating any discussion to another plane—of writing as if men were reasoning creatures, even if the evidence points to the contrary. Calmly and logically he showed that the novel is today "the representative and dominating literary work of art"—that the Jewish influence is not preponderant among the exiled novelists—that the international or European spirit, shared equally by Jewish and gentile writers, has helped to raise Germany from barbarism. And he added that the anti-Semitic campaign of the present German rulers "is aimed, essentially, not at the Jews at all, or not at them exclusively. It is aimed at Europe and at the real spirit of Germany."

So Mann at last has publicly joined those forces which, from Moscow and Kiev westward to Madrid and San Francisco, are bent on keeping alive the best of the old culture. Hitler's book-burning has had the effect of uniting his opponents in the defense of intellectual freedom—and notably it has cleared the atmosphere in Russia, has persuaded the Communist leaders that it is their duty to encourage those writers who are not dogmatic Communists. The law of polarity has ranged oppression on one side and liberty on the other. As for Mann himself, he has made his position in the conflict clear beyond question:

The deep conviction . . . that nothing good for Germany or the world can come out of the present German regime, has made me avoid the country in whose spiritual tradition I am more deeply rooted than are those who for three years have been trying to find courage enough to declare before the world that I am not a German. And I feel to the bottom of my heart that I have done right in the eyes of my contemporaries and of posterity.