I am a Jane Austenite, and, therefore, slightly imbecile about Jane Austen. My fatuous expression, and airs of personal immunity—how ill they set on the face, say, of a Stevensonian. But Jane Austen is so different. One’s favorite author! One reads and rereads, the mouth open and the mind closed. Shut up in measureless content, one greets her by the name of most kind hostess, while criticism slumbers. The Jane Austenite possesses none of the brightness he ascribes to his idol. Like all regular churchgoers, he scarcely notices what is being said. For instance, the grammar of the following sentence from Mansfield Park presents no difficulty to him:

And, alas! how always known no principle to supply as a duty what the heart was deficient in.

Nor does he notice any flatness in the second chapter of Pride and Prejudice:

“Kitty has no discretion in her coughs,” said her father; “she times them ill.”

“I do not cough for your amusement,” replied Kitty fretfully. “When is your next ball to be, Lizzy?”

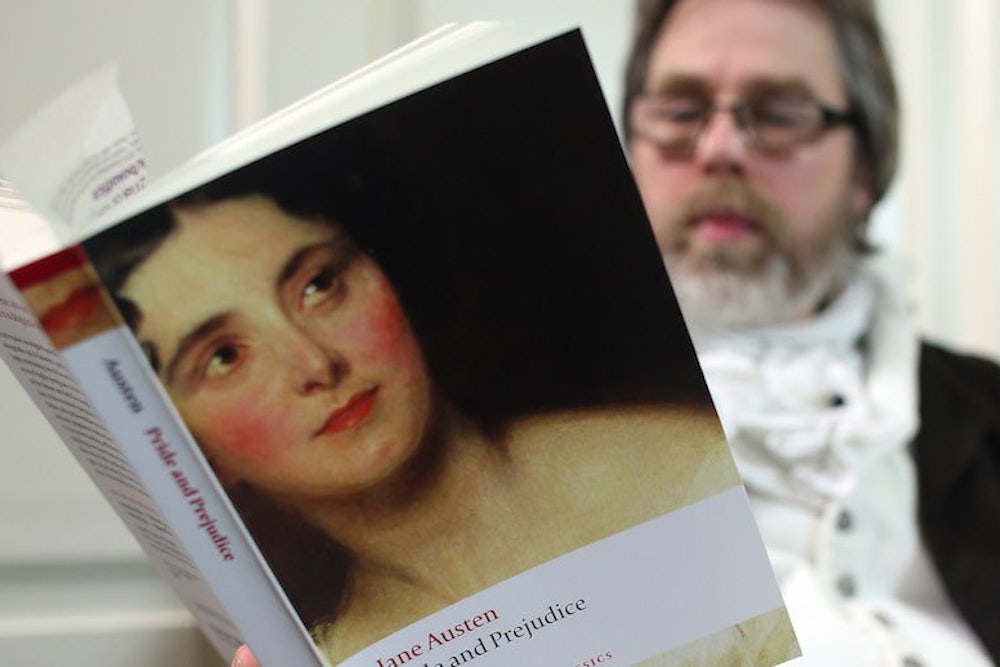

Why should Kitty ask what she must have known? And why does she say “your” ball when she was going to it herself? Something is amiss in the text; but the loyal adorer will never detect it. He reads and rereads. And this fine new edition has, among its other merits, the great merit of waking the Jane Austenite up. After reading its notes and appendices, after a single glance at its illustrations, one will never relapse again into the primal stupor.

Without violence, the spell has been broken. The six princesses remain on their sofas, but their eyelids quiver and they move their hands. Their twelve suitors do likewise, and their subordinates stir in the seats to which humor or propriety assigned them. The novels continue to live their own wonderful internal life, but it has been freshened and enriched by contact with the life of facts.

To promote this contact is the chief function of an editor, and Mr. Chapman fulfills it. All his erudition and taste contribute to this end—his extracts from Mrs. Radcliffe and Mrs. Inchbald, his disquisitions on punctuation and travel. Even his textual criticism helps. Observe his brilliant solution of the second of the two difficulties quoted above. He has noticed that in the original edition of Pride and Prejudice the words “When is your next ball to be, Lizzy?” began a line, and he suggests that the printer failed to indent them, and, in consequence, they are not Kitty’s words at all, but her father’s. It is a tiny point, yet how it stirs the pools of complacency.

Mr. Bennet, not Kitty, is speaking, and all these years one had never known! The dialogue lights up and sends little sparks of fire into the main mass of novel. And so, to a lesser degree, with the sentence from Mansfield Park. Here we emend “how always known” into “now all was known;” and the sentence not only makes sense but illumines its surroundings. Fanojr is meditating on the character of Crawford, and, now that all is known to her, she condemns it.

And finally, what a light is thrown on Jane Austen’s own character by a collation of the two editions of Sense and Sensibility. In the 1811 edition we read:

Lady Middleton’s delicacy was shocked; and in order to banish so improper a subject as the mention of a natural daughter, she actually took the trouble of saying something herself about the weather.

In the 1813 edition the sentence is omitted, in the interests of propriety: The authoress is moving away from the eighteenth century into the nineteenth, from Love and Friendship towards Persuasion.

Texts are mainly for scholars; the general attractions of Mr. Chapman’s work lie elsewhere. His illustrations are beyond all praise. Selected from contemporary fashion plates, manuals of dancing and gardening, tradesmen’s advertisements, views, and plans, etc., they have the most wonderful power of stimulating the reader and causing him to forget he is in church; incidentally, they purge his mind of the lamentable Hugh Thompson. Never again will he tolerate “illustrations” which illustrate nothing. Here is the real thing. Here is a mezzotint of The Encampment at Brighton, where the desires of Lydia and Kitty mount as busbies into the ambient air. Here is the soul of Sotherton in the form of a country house with a flap across it. Here is Jane Fairfax’s Broadwood, standing in the corner of a print that carries us on to Poor Isabella, for its title is Maternal Recreation. Here are Matlock and Dovedale as Elizabeth hoped they would be, and Lyme Regis as Anne saw it.

Here is a Mona Marble Chimneypiece, radiating heat. Mr. Chapman could not have chosen such illustrations unless he, too, kindled a flame—they lie beyond the grasp of scholarship. And so with the rest of his work; again and again he achieves contact between the life of the novels and the life of facts—a timely contact, for Jane Austen was getting just a trifle stuffy; our fault, not hers, but it was happening.

The edition is not perfect. Pedantry sometimes asserts itself; when Persuasion was published with Northanger Abbey, in 1818, its title did not appear on the back; but why should the inconvenience be perpetuated in 1923? And there is one really grave defect: Love and Friendship, The Watsons, and Lady Susan have all been ignored.

Perhaps there may be difficulties of copyright that prevent a reprint of them, but this does not excuse their almost complete omission from the terminal essays. There are many points, both of diction and manners, that they would have illustrated. Their absence is a serious loss, both for the student and for the general reader, and it is to be hoped that Mr. Chapman will be able to issue a supplementary volume containing them and all the other scraps he can collect.

There exist at least two manuscript-books of Jane Austen. The amazing Love and Friendship volume was extracted out of one of them; what else lies hidden? It is over a hundred years since the authoress died, and all the materials for a final estimate ought to be accessible by now, and to have been included in this edition.

Yet with all the help in the world, with a fine edition like Mr. Chapman’s and the best of literary criticism to our aid, how shall we drag these shy, proud books into the centre of our minds? To be one with Jane Austen! It is a contradiction in terms, yet every Jane Austenite has made the attempt. When the humor has been absorbed and cynicism and moral earnestness both discounted, something remains which is easily called Life, but does not thus become more approachable.

It is the books rather than the author that seem to elude us—natural enough, since the books are literature. “Dear Jane, however shall we recollect half the dishes?”

For though the banquet was not long, it has never been assimilated to our minds. Miss Bates, it will be remembered, received no answer to her portentous question; her dear Jane was thinking of something else. The dishes were carried off before she could memorize them, and Heaven knows now what they contained!—strawberries from Donwell, perhaps, or apricots from Mansfield Rectory, or sugar-plums from Barton, or hot-house grapes from Pemberly, or melted butter from Woodston, or the hazel nuts that Captain Wentworth once picked for Louisa Musgrove in a double hedgerow near Uppercross.