Quiet as it’s kept, the era of the “militant” black leader is over. Despite the fearmongering on Drudge and elsewhere, there are no black leaders calling for insurrection.

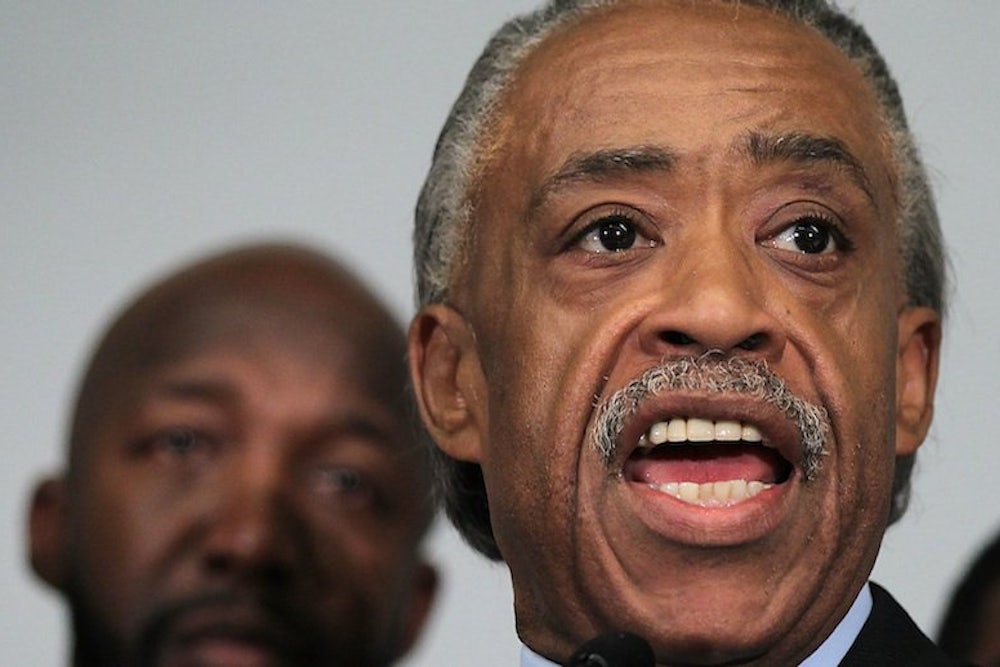

This is a good thing, because there was far too much of this type of performance over action in the bad old days. Bad old days such as 1991, when Al Sharpton was all but ringleading the race war between blacks and Jews in Crown Heights. “If the Jews want to get it on, tell them to pin their yarmulkes back and come over to my house,” Sharpton declared. Four years later, he was speechifying against the “white interloper” when a Jewish store owner was accused of driving a black store owner out of business in Harlem. Real leaders do more than perform—and this was pure performance.

But that kind of thing—or the kind of behavior that earned Jesse Jackson a similar reputation—was a while ago now. Some comment-section posts on my recent writings on the Zimmerman trial are by whites fuming in the same old way about Jackson and Sharpton whipping blacks up, but these Rip van Winkles are stuck in a recreational groove.

Yes, Sharpton is currently organizing cross-country, “Justice for Trayvon” rallies this coming weekend. But anyone who sees demagoguery in this might benefit from spending a week or so in Egypt. His 2004 criticism of Howard Dean for not including any black people in his Vermont administration—in a state with a black population of about 3000, many of them children—was cringe-inducing, but not meaningfully disturbing, and that was almost ten years ago now.

Meanwhile, Jackson’s career has been one long denouement since his fall from grace in a paternity scandal in 2000. His nasty comment about President Obama—specifically, that he wanted to “cut off his nuts”—during Obama’s rise to the presidency was a symbolic final curtain.

Today’s black leaders don’t strike notes like that: Cory Booker, Deval Patrick, and Allen West aren’t given to catcalls about yarmulkes. In 1990, black journalist Carl Rowan decried white criticism of Marion Barry in Washington, D.C. by stating that “the mayor may be a cocaine junkie, a crack addict, a sexual scoundrel, but he is our junkie, our addict, our scoundrel.” It is hard to imagine Ta-Nehisi Coates taking that line today.

In truth, the influence of people like Jackson and Sharpton was always exaggerated. In the teens and ’20s, Marcus Garvey was a rock star among black Americans, preaching an anti-white, back-to-Africa rhetoric with theatrical showmanship and slogans rather than feasible plans. Yet most blacks just siphoned-off a message of general pride and went home to support sober, all-black districts like Chicago’s Bronzeville, which is thriving at this very time. Like all people, black Americans can thrill to rhetoric without embracing all its implications. Remember the church our President turned out to be attending?

The decline of Sharpton-esque demagoguery does not mean that things are universally looking up in the way we talk about race. In 2000, The New York Times ran a think piece on the state of black America in which black psychologist Beverly Daniel Tatum intoned, “A cultural system is operating to reinforce cultural stereotypes, limit opportunities and foster a climate in which bigotry can be expressed.” Columbia Law School professor Patricia Williams informed us of the “violently patrolled historical boundary between black and white in America,” and psychiatry professor Alvin Poussaint told us that interracial dating is still something many “fear.”

Today, in the wake of the Zimmerman trial, surely such a think piece would have a similar air, only with newer faces, such as Charles Blow and Melissa Harris Perry. Alongside preachers, the black intelligentsia surely plays a key role, and among them there remains a core contingent with a deeply pessimistic take on the state of black America. To them, the fate of Trayvon Martin says much more than Obama’s presidential victories, the lowest rate of black housing segregation since the Harding Administration, or the fact that the class-based gap in scholastic performance is now greater than the racial one.

But there are not, and never have been, any new versions of the old Jesse and Al. Not a single young preacher or politician has even started to acquire national influence by taking a page from their old playbooks. The times have changed. If the more pessimistic strains in black America can be slow to fully acknowledge progress, we can take heart from the fact that Al Sharpton will be 60 next year, and a young version of his young self is now inconceivable as a national figure.

John McWhorter is a contributing editor at The New Republic.