After Election Day, the conventional wisdom was that the GOP needed to make gains among Hispanics to win in 2016. Fox News' Brit Hume and Sean Hannity, for instance, quickly assessed the GOP needed to cave on immigration reform. Half a year later, Hume and Hannity have flipped. Hannity doubts that immigration will help Republicans, while Hume says the demographic arguments are “baloney,” since the Hispanic vote is “not nearly as important, still, as the white vote.” Hannity and Hume aren’t alone. Rush Limbaugh, for instance, says white voters stayed home because the Republican Party didn’t stay conservative enough. And as MSNBC’s Benjy Sarlin put it, “you can hear the ‘missing whites’ thesis everywhere if you look for it.”

That thesis has led conservatives to embrace a different electoral strategy than their more moderate counterparts: more gains with white voters.

Sean Trende of RealClearPolitics makes the strongest case for a whiter Republican coalition. In a four-part demographic tour de force, he argues that the GOP doesn’t have much to gain from immigration reform, since Hispanics just aren’t a very big part of the electorate and immigration reform wouldn’t yield big GOP gains among Hispanics, anyway. Instead, Trende says the GOP should deepen its existing coalition by making additional gains among white voters, energizing the missing white voters, and counting on a decline in black support for the next Democratic candidate.

As a matter of arithmetic, Trende is right: Hispanics were only about 9 or 10 percent of the electorate in 2012, and Obama won the national popular vote by 3.9 points. For the GOP to gain 3.9 points out of 9 percent of the electorate, they’d need to improve by a net-43 points with Hispanics, all but eliminating Obama’s 44 point margin of victory. That isn’t going to happen in a competitive election. The importance of Hispanics is further reduced by the Electoral College, since they are disproportionately concentrated in solid red or blue states: Hispanics represent more than 5 percent of the electorate in only three of the twelve most competitive states.

Massive GOP gains among Hispanics just couldn't have elected Romney. Only Florida would have flipped. And since Hispanics are just a fraction of the electorate in many of the most pivotal states—like New Hampshire, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—it’s conceivable that the next GOP victory might not involve big gains among Hispanics. That’s why I’ve argued here, here, here, and here that the focus on immigration reform and Hispanics is misplaced. And that’s why immigration reform is more important as a test of the GOP’s willingness to rebrand than as a means to single-handedly secure the White House.

But the GOP will have to compensate with gains elsewhere if it forfeits marginal but meaningful opportunities among Hispanics. Demographic changes are turning the Bush coalition—which combined white conservatives with a few targeted inroads among sympathetic groups—into a coffin. Every four years, the non-white share of eligible voters increases by 2 points, requiring Republicans to do a little better to compensate for demographic change. Plugging the 2004 results into 2016 demographics, for instance, would yield a Democratic victory. And to counter demographic changes by 2016, the GOP will need broader appeal than it’s had since 1984—a high burden. And that burden becomes even greater, even if only marginally, without inroads among Hispanics.

But Trende’s case is so appealing to conservatives because it implies that Republicans don’t need to make any compromises whatsoever to make additional gains among white voters.1 There is indeed room for the GOP to improve among white voters, but there’s no reason to think it won’t be painful, too. If Republicans don’t want to compromise on immigration reform, they will probably need to do something else to make up ground. It could be moderating on social issues or economics—or a little bit of both. Either way, the GOP will have to pick its poison.

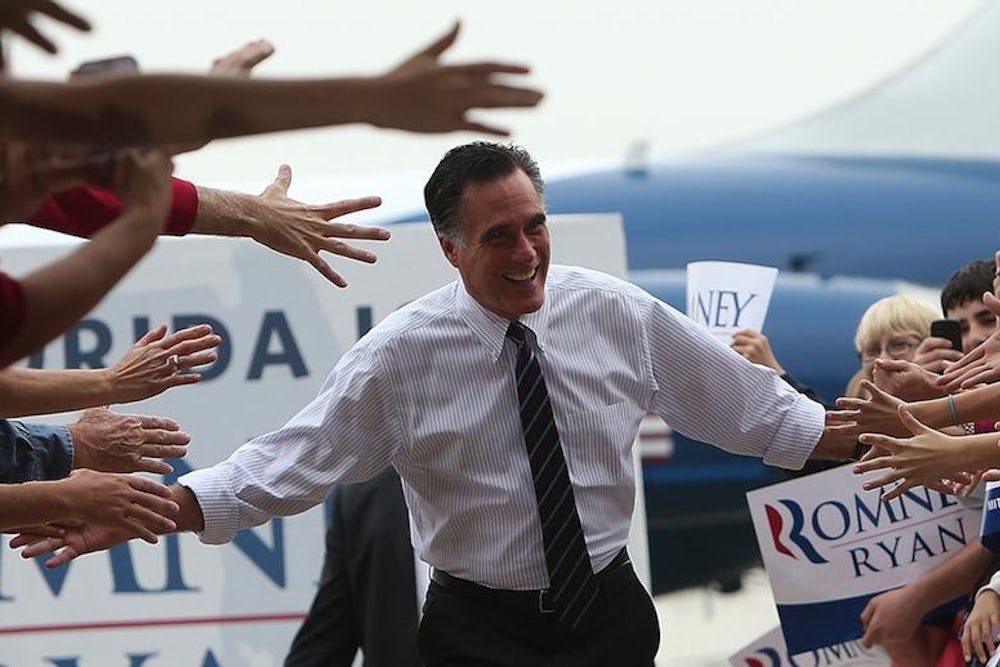

The case for GOP optimism rests on the hope that the party’s steady gains among white voters will continue. The national trend among white voters does look good for the GOP. Last November, Romney did extremely well among white voters, reaching about 60 percent of the white vote—the best Republican performance since 1988. Over the longer term, white voters have indeed shifted against Democrats: Obama did worse among white voters than Kerry, who did worse than Gore, who did worse than Clinton. As a result, Trende thinks it is “touchy to assume that the GOP will max out at 60 percent of the white vote,” which Romney scored last November, and he doesn’t “see a compelling reason why these trends can’t continue.”

But the GOP’s gains among white voters aren't national. They're almost exclusively among southern and Appalachian voters. Outside of the South, there’s no clear trend. And Democrats might have even made gains among whites outside of the South, both absolutely and with respect to the national popular vote.

The following map compares Obama’s performance in 2012 with Gore’s in 2000. The colors are a bit counter-intuitive: Red indicates areas where Obama did better than Gore, and blue shows where Obama did worse than Gore. But if you know the geography of race and fossil fuel production in the United States, the lesson of this map is extremely clear: Democrats have a problem with Southern whites, not all whites.2

Suddenly, Romney’s performance among whites doesn’t seem so historic. And once you think about it, that’s not very surprising. He lost New Hampshire and Iowa, two white states carried at least once by Bush, and lost Wisconsin by 7 points. And notice that this pattern isn’t limited to well-educated metropolitan areas—the trend is evident in both working class and well-educated communities.

Trende doesn’t think that these regional trends undermine his argument. After all, the collapse of Democrats in the white South has given the GOP states like West Virginia, Kentucky, Arkansas, Missouri, and Louisiana. But since 2000, the benefits of moving states like Virginia and Colorado from red to bluish-purple have outweighed the costs of making red states redder, or the losses among southern or Appalachian whites in Pennsylvania or Florida, which haven’t even been sufficient to budge their own states.3

If these trends among white voters continue, it is not news good for Republicans. On balance, it would cement the Democratic edge in the Electoral College. Yes, there might be additional Republican gains in eastern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, or northern and central Florida, but these regions aren’t populous enough to decisively offset Democratic gains elsewhere in those states. In contrast, the GOP is losing more ground in New Hampshire, Iowa, Colorado, Virginia, North Carolina, Wisconsin, or even Ohio, where Democrats have made gains around Columbus and in the northwestern third of the state.

It’s also possible to envision how Democrats make additional gains among northern whites. Obama won young white voters by a decisive margin outside of the South. To date, the Democratic lean of young voters has been canceled out by the departure of the Democratic-leaning “Greatest Generation,” as the Guardian’s Harry Enten has convincingly argued. But with the “Greatest Generation” reduced to just a sliver of the electorate, the pace that generational replacement moves the national white vote leftward might accelerate, since the Republican-leaning “Silent Generation” is next to go. At the very least, the end of the “Greatest Generation” is one reason why we wouldn’t expect a strong, anti-Democratic trend to continue.

The extent that young voters can push the national white vote leftward depends on whether the next cohort of young voters is as liberal as today’s 18- to 29-year-olds. If today’s young whites tilt Democratic in large part because they’re less religious and are outraged by the GOP’s stance on cultural issues, then perhaps their similarly secular younger brothers and sisters might vote Democratic, too. On the other hand, to the extent that white millennials are particularly Democratic because they came of age during the Bush administration, which was widely viewed as disastrous, then the next wave of white millennials should be more competitive. The answer probably lies somewhere in between, but one piece of evidence points toward the latter scenario: Obama’s collapse among young whites since 2008, when he fell from winning them by 10 points to losing them by 7 (although Obama probably carried non-Southern young whites by a wide margin). Of course Obama still did 16 points better among young whites than older whites, but the big swing between ’08 and ’12 raises uncertainty about the eventual preference of today’s teenagers.

One opportunity for Republicans is the “missing white voters”—those who didn’t turn out in 2012, but did in 2008 and 2004. But Republican opportunities with “missing white voters” are pretty marginal. Just as the GOP can’t erase Obama’s margin with Hispanics, it can’t assume that every missing white voter was a conservative. According to the Census, 40 percent of the drop-off was from 18-24 year old whites—not easy targets for the GOP. The “missing white voters” are also missing in most of the battleground states, just like Hispanics. Turnout was flat or up in some of the whitest battlegrounds, like Colorado, Iowa, Wisconsin, and New Hampshire. Obama's success in these high turnout, white areas calls into question whether their missing compatriots were especially GOP-friendly. And it's not like there aren't millions of missing non-white voters, too.

The only mutually contested state where turnout fell by a meaningful amount was Ohio, but turnout fell by a similar amount in Democratic base counties like Cuyahoga, Lucas, Mahoning, and Trumbull—making it harder to argue that higher turnout would have clearly helped Republicans, and casting doubt on the exit poll finding that black turnout surged in Ohio. But even if most missing voters in Ohio were conservative, it wouldn’t have flipped the state: Turnout dropped by 130,884 votes in Ohio, but Obama won by 166,272.

There are two ways to view the Democratic resilience, or even strength, among non-southern whites. On the one hand, there’s room for Republicans to improve among white voters. That gives the GOP a route to the presidency without big gains among non-white voters, at least for now. On the other hand, it casts doubt on the view that Republicans will inexorably gain among whites, at least outside of the South.

Reversing the anti-GOP trend among non-southern white voters will probably require changes in messaging or policy, probably by moderating on both economic and cultural issues. The Electoral College encourages the GOP to make gains across a diverse swath of swing states, and they need to push back against the equally diverse Democratic attacks that have hobbled the GOP: the attacks on cultural issues that hurt Republicans around Denver, Washington, and Columbus; the depiction of the GOP as the party of the elite, which has hurt the GOP just about everywhere; and yes, the challenges immigration reform poses in Las Vegas, Denver, Orlando-Kissimmee, and Miami.

Yet conservatives take solace in the possibility that they could win with gains through whites, presumably on the assumption that the changes needed for gains among non-southern white voters will be less painful than embracing immigration reform. To the extent that this assumption is informed by the view that the GOP is making broad, steady gains among white voters, it is wrong. The GOP has a tough road ahead.

To be clear, Trende believes the GOP needs to change, especially on economic issues. But it seems that Trende still thinks that white voters will trend toward Republicans with respect to the country, regardless of whether they embrace his proposed reforms. And even if I have misunderstood Trende on this point, many conservatives still seem to assume that they can do better with whites while pressing their existing, conservative message.

The arch of red across the South is where heavy black turnout and support for President Obama swamped the anti-Democratic trend among Southern whites.

"PVI" measures the performance of a state with respect to the country, so Gore's margin in Colorado was 8.88 points worse than it was nationally. There's a legitimate debate about whether it's best to compare PVI or margins when assessing the consequences of demographic change. On the one hand, PVI helps correct for national-level effects, like the economy. On the other hand, it also corrects for demographic changes--if the non-white share of the electorate keeps growing, whites would appear to "trend" Republican, even if the GOP never made any gains among Republicans at all.