May 6, 2012 in Moscow was warm and sunny, one of the first days of spring that you could walk around without a jacket. Katya Minsharapova was wearing a light summer dress, the kind that got a few extra seconds of attention from strangers on the hour-long subway ride from the suburb of Altushyevo to the center of Moscow. Katya, who is 24 years old, and has a warm, pretty face, had arrived in the center of town with her 22-year-old boyfriend, Andrei Barabanov, for an antigovernment protest scheduled for later that day.

Minsharapova and Barabanov’s politics were more curious than fully articulated. They knew they were dissatisfied with the current order of things, with venal officials and the poor state of education and unsatisfying job prospects. She was trained in airbrushing; he helped with designs and braided friends’ hair into dreadlocks for spare cash. The couple was political in the way that many young people in Moscow were a year ago: energized for the first time about the prospect of changing how they were governed, and perhaps a little naïve about the ease of doing so.

A round of protests earlier that winter, following fraudulent parliamentary elections, had been marked by a certain buoyancy, a sense, however short-lived, that wit and logic might just be the thing that could undo the cynicism of the Putin system. Minsharapova later recalled “the positive atmosphere,” at the earlier protests. “Everyone was smiling, happy. There was no hatred, no ill-will.” That idealism about change now seemed misplaced. The gathering on May 6, after all, had been called to protest the next day’s re-inauguration of Vladimir Putin, who was treating his return to power as a virtuous and redeeming triumph.

With Moscow largely empty thanks to Russia’s annual May holidays, the demonstration offered the opposition and its supporters a chance to act out their frustrations that they didn’t achieve more—at least not yet—and to hold a defiant Irish wake for the winter protest movement. Estimates of the crowd on May 6 would later vary, but it seemed possible that around 40,000 people had shown up—less than the 100,000 that came to rallies that winter, but far more than had ever attended a political demonstration at any other time in the Putin era. Those who joined represented a mix of Russia’s political ideologies and social classes: older liberals, far-left socialists, young professionals, nationalists, and anarchists.

Mikhail Kosenko, who is 38 years old and has a long mustache and droopy eyes, came by himself. Once a sharp-witted high school student, he had suffered a brain injury in the army service in the late 1980s after being beaten by fellow cadets. Doctors pronounced him medically disabled; for years after, he mainly stayed inside the Moscow apartment he shared with his sister and her adult son, listening to the radio and reading books on communist history.

Artem Savelov also came alone. Savelov is 33 years old, with a boyish face and a wide smile that curves upward somewhat mischeviously; if not for the silver streaks in his hair, he could pass for a teenage skateboarder in California. He has strong stutter that came on as a young boy.

Denis Lutskevitch, a handsome, solidly built 21-year-old university student who had served in an elite marine infantry unit, came with some classmates. He had marched through Red Square for the annual May 9 military parade the year before, and his mother, Stella, told me that afterward, “He came home with such pride. He had such a smile.” Lutskevitch was thinking of joining one of the Russian security agencies, perhaps the Federal Guard Service, which protects Putin and other officials, and had already been called for an interview. He didn’t have pronounced political views; he came to the protest mainly because his friends seemed intrigued. Maybe he could watch over them if things got messy.

Stepan Zimin, who is 21 years old, showed up with some fellow anarchist friends. As is the fashion among anarchist street activists, they all wore surgical masks over their faces. Zimin had diverse interests: He was studying Arabic at the Russian State Humanities University in Moscow and liked to spend weekends dressing up for medieval historical reenactments.

The march was meant to snake its way from the Lenin statue at October Square to Bolotnaya Square, just across the river from the Kremlin and the site of a large protest earlier that winter. They never made it. After marching down the wide thoroughfare of Yakimanka Street, passing the headquarters of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the French Embassy, they reached a bridge that leads to the Kremlin walls. There, a cordon of riot police in shoulder pads and plastic visors—their imposing yet awkward getup has given them the nickname “cosmonauts”—was blocking the flow of marchers toward the stage set up on the square.

Some people toward the front, unable to move any further because of the police, sat down. Others shouted to keep marching but couldn’t agree on a direction: to the right, straight into the police, back toward the start of the march. Negotiations, to the extent there even were any, went nowhere. So marchers sat on the hot asphalt, yelling at police and singing protest songs, but mainly not knowing what was going on.

About an hour later, a handful of protesters broke through the police line. Officers swung their batons wildly. Chunks of asphalt went flying. As slowly as events had unfolded an hour earlier, they were now moving quickly. Activists wearing scarves over their faces tossed flares that soared in a flash of yellow sparks toward the police. Every few minutes, riot troops would form into lines and push into the crowd, knocking down some people and grabbing others for arrest. Tufts of dark gray smoke, set off from grenades launched by demonstrators or provocateurs—or both—masked an ugly scene of metal and plastic and flesh.

Lutskevich was separated from his friends from the university. He would later tell his mother that he saw a young woman being grabbed by the police; he lunged to try and free her. Officers went after him, managing only to rip off his shirt. He stood on the square, naked from the waist up, looking for others who might need help. A few minutes later, he was surrounded by as many ten officers in riot gear, who kicked him and beat him with rubber truncheons. He was arrested and carried away.

Minsharapova, who is just under five feet tall, couldn’t see much of anything. A knot of police swept through the tightly packed crowd, lifting her up into a crush of people and separating her from Barabanov. “I understood right away that I wouldn’t be able to find him,” she recalled. “He’s gone. And I start to panic. I had his mobile phone in my bag, so I can’t call him. I can’t see him. Where we were just standing, there now isn’t anybody.” Twenty or so minutes later she got a call from an unknown number: it was Barabanov on a borrowed phone, telling her he’d been beaten and detained by the police and was now sitting in an avtozak, an armored police van. Zimin and Savelov were detained, too.

In total, more than 450 people were arrested that day. All were held just a few hours, or at most overnight, and given administrative summonses and small fines. The next morning, a judge gave Barabanov the token sentence of the night he spent in jail and released him. Police took Lutskevich, his face and back covered in bulbous welts, to a hospital, where doctors had a look at him and let him go. Kosenko was also caught up in the clashes and was arrested. He came home and told his sister, Kseniya, he would have to pay 500 Rubles, or about $16. That’s not so bad, she thought. “My son and I even laughed,” she said, “at how he got off so cheaply.”

Today, the events of May 6, 2012—and more important, how the Russian state has chosen to respond to those events—are regarded as an inflection point in the Putin era. Before that day, it was relatively safe to be a regular, anonymous supporter of the opposition; afterwards, that was no longer the case. For more than a decade, Putin and those around him had managed to secure their rule with clever games of cooptation and manipulation. Now they would now rely on blunter tools. The good times of the 2000s, fueled by rising oil prices and Putin’s general popularity, allowed for a delicate touch in maintaining control. May 6 is when things began to get a lot rougher. One year on, the events of one chaotic afternoon have morphed into large-scale prosecutions that are shaping up to be the defining piece of political theater in the new age of Putinism.

The immediate days after the protest were strange ones. On his way to the Kremlin for his inauguration ceremony on May 7, Putin and his motorcade glided through the streets of the capital that had been cleared of nearly all its citizens. On television, the spectral ceremony created the impression of an aloof emperor fearful of his subjects, or at least wholly detached from them. Still, the protest mood lingered, now manifested in momentary gatherings of a few dozen people in public squares or along the city’s boulevard ring. They would be chased away by police, only to pop up across town an hour later.

A few days after the inauguration, Moscow’s mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, made a show of visiting injured officers in the hospital, promising them apartments in Moscow as thanks for “preventing an act of provocation.” Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, was less subtle. Police should “smear their livers on the asphalt,” he said of street protesters. The Investigative Committee, a powerful body equivalent to the FBI, announced that it was opening a criminal case relating to calls for mass riots on May 6. Two hundred investigators were put on the case. Most of the investigation centered on watching the hours of footage taken on the square and combing the records of those detained the day of the protest.

The arrests began on May 27 with a 19-year-old student at Moscow State University. Around 10 p.m. the next night, Barabanov was at home with Minsharapova and his 55-year-old mother when the lights went out. His mother walked out to check the fuse box and found a group of men in black masks carrying machine guns. The men burst into the apartment, throwing Barabanov to the floor. Once the men had taken him away, one came back to show his mother an arrest warrant.

Police came for Zimin on the morning of June 7. A friend of his girlfriend, Sasha Kunko, wrote her around lunchtime to ask, “Are you aware of what’s going with Stepan?” She didn’t believe it—until she checked the news on the website of the Investigative Committee. At 9 p.m. that same evening, the buzzer rang at the apartment Kosenko shared with his sister and her son. A “whole crowd” of men walked in and announced that they had a search warrant. Four of them grabbed Mikhail. He was taken to Petrovka 38, the headquarters of the Moscow police force.

Two days later, Lutskevich was arrested; police showed up at his mother’s apartment at four in the morning. Savelov was arrested the next day, while his father was away at their dacha. When the father returned, the apartment was a mess; things had been thrown all over the place. Moscow police called in the middle of the night to say his son was being held.

In the immediate hours and days after the arrests, according to the defendants and their lawyers, investigators were most concerned with pressuring those detained—all rank-and-file activists, or merely “accidental passengers,” in the words of one lawyer—to finger known opposition leaders as having orchestrated the events of May 6. Lutskevich’s lawyer told me that in the first days of his detention, interrogators pushed Lutskevich to sign a statement saying he had been directed by a group of known anti-Putin leaders including Alexei Navalny, the anticorruption blogger who is the closest thing the Russian opposition has to a star, and who currently faces his own politically motivated trial.

“I don’t even know what they look like,” Lutskevich told the police, according to his lawyer. The response: “Well if you don’t want to cooperate, that means you’ll sit in prison.”

When Kosenko was examined by medical staff in jail, his lawyers say, doctors spent more time asking him about his political affiliations than about his medical background. He was not given the medication he had taken regularly for ten years, an antipsychotic called thioridazine. After a small outcry in the Russian press—his lawyers got word to independent journalists—he got his medication, though not always regularly, according to his sister and his lawyers.

After Savelov’s first court hearing, an investigator told his father that the 33-year-old was facing eight to ten years in prison, but if he would “cooperate” with the investigation—name opposition leaders as the organizers of the May 6 clashes—then he could get just two to three years. “And so loudly, right there, I ask him, ‘Are you ready to sit in prison for two or three years for nothing at all?,’” his father recalls. “He stammered, and then walked away. I said, ‘You see! You don’t want to spend that time in prison, but someone else should, just like that.’”

One day recently, I went to see Natalia Taubina, the head of the Public Verdict Foundation, a Russian legal-aid group representing a handful of the May 6 defendants. As we sat in her office, she tried to explain the process of criminal investigations in Russia, especially in politically sensitive cases. First, she said, the state settles on a version of an event—in the case of May 6, mass riots organized by opposition leaders. Then, she said, various judicial and law-enforcement bodies do not engage in “an investigation of an event in order to understand what actually happened, but in the reconstruction of an event so as to match a certain version.” In the end, she said, the Russian criminal-justice system decides cases according to an equation made up of bureaucratic momentum, a reverence for clean statistics, and the interpretation of signals passed “intuitively and harmoniously” from politically powerful offices and individuals—Putin, to be sure, but not only him.

Over the months of reporting this story, I tried to speak with Moscow police, responsible for security on Bolotnaya Square last May 6, and the Investigative Committee, in charge of the criminal investigation and arrests that have followed over the past year. They refused to meet with me or provide comment, citing the ongoing case and pending trial. I did, however, manage to pass some questions to an investigator working on the May 6 case through Svetlana Reiter, a Russian journalist who has done an extraordinary job covering the evolution of the case over the last year. The investigator said that “operatives have spent a whole year watching videos taken on the square by law enforcement agencies and journalists,” and are continuing to hunt for new suspects. “This work is ongoing and will continue until they find everyone they can.” The investigator denied the case has any political resonance, saying it is “a routine matter that has nothing to do with politics; it has received close attention due to the fact that police officers received trauma and bodily injury.”

There are now 28 people charged as part of the May 6 investigation. Most face the same two charges: using force against a representative of the authorities and participating in mass riots. If convicted, the defendants face up to 13 years in prison. On the first allegation, in many cases the only evidence is the testimony of those the state has identified as victims and witnesses: the police officers present that day. This approach has produced some irregularities, with police changing their statements or remembering key details long after the day itself. The two police witnesses against Alexei Gaskarov, a 27-year-old activist, only appeared nearly a year after the events of May 6. They were suddenly were able to pick out Gaskarov as having struck another officer and as being the leader of a group of young people “dressed in sportswear.”

Similarly, Vassily Kushner, a lawyer who has represented Zimin, told me that the police officer who is the official victim in the case against his client said nothing about his injuries or Zimin when first interviewed in the days after the May 6 protest. Then, early last June, he told investigators about a broken finger he suffered on May 6—and that it was caused by Zimin throwing a stone toward police lines. Later, a different officer from the same unit as the alleged victim contradicted that story, telling an investigator that he saw Zimin throw stones on May 6 but not in the direction of either officer. At this, according to Kushner, the investigator leaped up and yelled, “You better speak the truth or we’ll open a case against you for misleading investigators!” (Kushner also said that the investigator made a point to describe photos that Kushner had posted online from his family vacation in Spain. “We keep track of everything,” he was told.)

The state’s sealed indictment against the May 6 defendants, which comprises more than 60 volumes, abounds with questionable facts, according to the parts of the document that are publicly available and to several defense lawyers and others who’ve been able to review it (the entire document is not publicly available). For instance, it alleges that Savelov, with his near crippling stutter, led the crowd in rounds of antigovernment chants. It says that the police officer allegedly struck by Kosenko suffered a concussion, even as the witness to the alleged assault, another police officer, says only that he saw Kosenko beat the officer in the arm and body—not the head.

In comparison with the first set of charges, the second—participating in mass riots—is more theoretical. When does a protest become a riot? One of Kosenko’s lawyers, Valery Shukhardin, explains that Russian jurisprudence defines mass riots as a kind of coordinated pogrom involving “arson, destruction of property, use of force toward fellow citizens.” A spontaneous outburst of accidental violence would not seem to qualify—a point that is likely to form one of the defense’s key strategies.

This line of argument gained some momentum in February, when the Kremlin’s human rights council released a statement that said police, not protestors, were largely to blame for the violence, and that the classification of mass riot “does not reflect the reality of what happened.” The council is technically powerless and frequently ignored, but in this case even some within the security services apparently agree: An internal police investigation leaked to The New Times, a liberal weekly, states that officers were able to maintain public order on May 6 and that “an emergency situation was prevented.”

Ultimately, what the bosses want, the bosses will receive. At his annual press conference last December, Putin said that going to a protest in and of itself should not send a person to prison—but assault against a law enforcement officer must be punished. Again, the signal was clear enough. The next day, investigators delivered some news to Alexei Polikhovich, a 22-year-old university student who, unlike most defendants, had only faced the mass riot count. Now he would face the other charge as well: A policeman had just remembered that Polikhovich beat him on the arm.

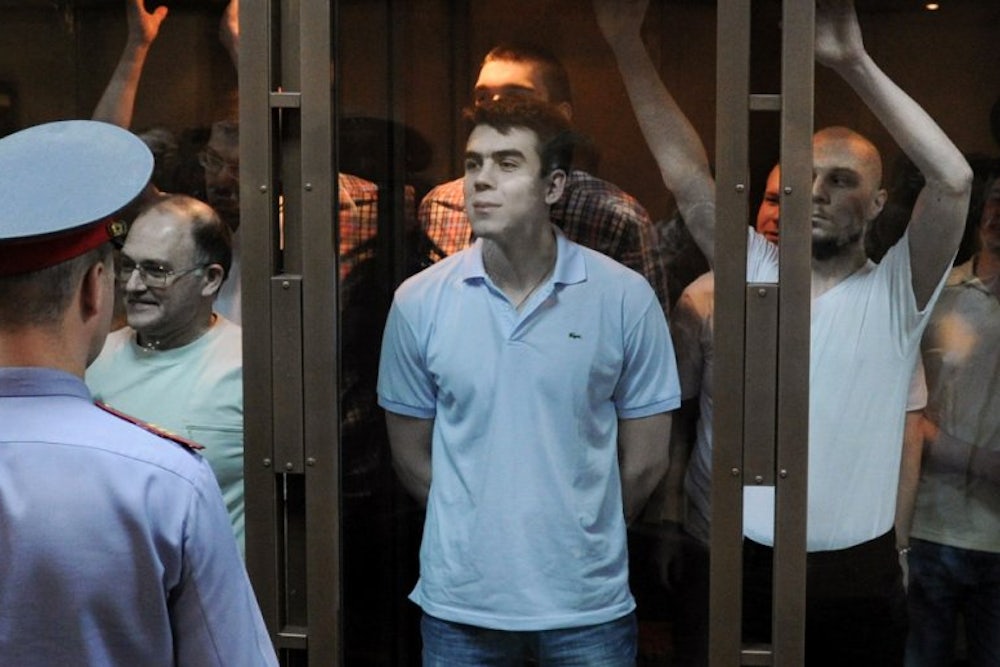

As they await trial, the majority of the May 6 defendants are being held at one of Moscow’s five pretrial detention facilities. Although Russian judicial guidelines call for those facing the particular charges entered against the May 6 defendants to be granted bail or home arrest, judges at successive rounds of hearings extended the suspects’ detention many times over.

Unlike in the old days, they are not entirely cut off, or even entirely without access to friends. Yes, the state-run television channels shown in jail will occasionally air a report on the May 6 case: a new suspect has been arrested, the Investigative Committee has opened a new charge against an opposition leader. But the prisoners can also subscribe to independent newspapers; the fiery and liberal Novaya Gazeta is a favorite. Anna Karetnikova, a member of a commission that moitors Russian prisons, told me about visiting a left-wing detainee whose message for the outside world was, “Tell my comrades that we must categorically condemn the repression of the working class in South Africa.” As Karetnikova remembered, “I’m standing there thinking, I didn’t even know of anything that happened in South Africa.”

Zimin for a while found himself in an even more unlikely circumstance. He shared a cell with a rich guy awaiting trial for fraud; the cellmate paid for a host of welcome luxuries for the enclosure: a refrigerator, a fan, a plasma TV.

One night not long ago I sat at a café near Tretyakov Gallery with Sasha Kunko, Zimin’s girlfriend, who is 25 years old and works at a Moscow publishing house. She and Zimin had been dating for just two months before he was arrested. The two met as swing dance partners—last year, they reached the finals of the Russian championship in boogie-woogie—and have now spent far more time as couple with Zimin in jail than when he was free. Theirs is a courtship of jailhouse letters and conversations through thick glass, giving their relationship an intensity both tragic and intoxicating.

Kunko told me about his letters to her, in which he fantasized about taking her for a stroll through Moscow in the rain. She was going the next morning to jail for another visit. “Everyone there is sad, mournful,” she said. “Our meetings are happy. We try to joke. ... We have to not take it so seriously, even though it’s absurd and nightmarish.” Every now and then, as we were talking, Kunko would pause to cry “Of course we’re afraid,” she said. “We understand where we are seeing each other and why.”

Adding to the impression of procedural correctness, the Russian prison service also has an efficient Internet portal for sending letters to those behind bars—the May 6 defendants have gotten dozens, if not hundreds, of letters—but replies may be censored. I wrote letters to half a dozen; I received only one back, from Mikhail Kosenko. I asked him about his life in prison and how he relates to the social resonance of his case.

“Greetings, Joshua!” it began. He wrote that he does not feel the center of any of kind of attention, and that information gets to him only in “vague echoes.” He asked me how the May 6 case is discussed in the West. As the one-page letter went on, it became more scattered and free form—though that gave it a loose, almost koan-like quality. “People write me letters in their thoughts, I know this,” Kosenko wrote, apropos of nothing. In between sentences describing the New Year’s cards he received in jail and the help he has gotten from his sister, he wrote: “Just as the incoming surf breaks against the rocks, the experience of a person in prison breaks against the lack of freedom.”

Since his arrest, psychiatrists from the state-run Serbsky Institute have declared Kosenko insane, writing that he “poses a threat to himself and to the people around him, and needs to be committed to a medical institution.” His case is now being heard separately; if found guilty, he will be sent to a psychiatric hospital.

As for the rest, the Investigative Committee has now passed the cases of the first 12 defendants on to court—including Barabanov, Savelov, and Zimin. The trial itself begins June 24. The remaining defendants will be tried in batches throughout the coming months, all part of the same overarching May 6 case. “It’s impossible for it not to be a show,” one lawyer told me; he said the process could last more than a year and involve as many as 400 witnesses on each side.

No one is especially optimistic. The one May 6 defendant who pled guilty, Maxim Luzyanin, a 36-year-old gym owner, was sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison—more than nearly anyone expected for someone who had ostensibly cooperated with the investigation. “He didn’t go for the kind of compromise that was actually wanted or expected of him,” says Sergei Davidis, who heads the program on political prisoners at the human rights group Memorial.

I asked Davidis how he thought the trial would end. “Will the court give them a year? Or five? That will be an indication of what the state is thinking,” he said. “But they won’t be acquitted and freed, that’s for sure.” That’s partially a recognition of the political nature of the trial, but beyond that, in just about any case, the Russian criminal justice system moves in one direction only; switching into reverse is something approaching a mechanical impossibility.

The number of those soon to appear in the “aquarium”—the nickname for the glass-walled cage where defendants sit in Russian courtrooms—could have been even larger if not for those who fled the country ahead of possible prosecution. Around 50 people have left in total, according to activists and journalists. One May 6 suspect who left, a 36 year-old rocket engineer named Alexander Dolmatov, committed suicide at a deportation center in Rotterdam in January. His application for political asylum in The Netherlands had been rejected. His Dutch lawyer, Marq Wijngaarden, told me that his client’s behavior “radically changed” and that he had been convinced he was “contacted and possibly threatened” by Russian security services.

Over the past year, the May 6 defendants, even those at the same jail, have been kept in separate cells and have not had much chance to meet one another, though many have come to feel bound together by fate and circumstance. Some have remained apolitical; others have started to carry themselves as oppositionists. As Zoya Svetova, a noted journalist for The New Times who covers the prisons, and has visited many of the accused, told me, “They have been confronted with the lawlessness of the state, they see they are being held in jail for nothing. They see they are victims of a political decision. They read about themselves in Novaya Gazeta. They deny their guilt, and in so doing, begin to feel like heroes.”

No matter how the trial unfolds, the state has already achieved part of its goal: The sweeping investigation into the violence and the random, or at least unpredictable, pattern of arrests is meant to frighten and splinter the opposition and those who might support it. The crowds at protests have certainly been smaller in the past year; part of that is surely a result of deterrent effect of the May 6 prosecution and the overall sense of gloom that has descended over much of the opposition movement.

Beyond that, the authorities appear intent on using the case to create a master narrative of the protests, in which opposition leaders gathered money from murky sources abroad to organize mass riots carried out by their foot-soldiers in the streets. This act in the country’s ongoing political theater became clearer in January, when the Investigative Committee announced it was combining the May 6 case with another ongoing criminal investigation: the probe into claims made in a television documentary, “Anatomy of a Protest-2,” aired last October.

That gloomy and conspiratorial purported documentary alleged that far-left activist Sergei Udaltsov, among others from the Russian opposition, met with a Georgian politician to discuss carrying out a campaign of political terror in Russia—including the “mass riots” of May 6. An offscreen voice ominously suggests, “An action plan has already been mapped out, and its masterminds are outside Russia,”1 In linking the charges against Udaltsov and others with those against the May 6 defendants, the Investigative Committee said in a statement that is has “grounds to believe that the crimes in question were all committed by the same people.” Uldatsov is now under house arrest.

Another defendant, a leftist activist and Udaltsov associate named Konstantin Lebedev, shocked his onetime allies by announcing in April that he was pleading guilty and cooperating with investigators. He was sentenced to two and a half years. In an interview with Kommersant, he said he did not consider himself a “traitor” and only “admitted the obvious.” (Among other far-fetched plots, Lebedev said the gang considered or smearing valerian root—a kind of catnip—all over Moscow’s FSB headquarters, so that the building would be swarmed by hundreds of cats.)

Moscow political circles are now caught up in guessing whether Lebedev was a sleeper agent planted long ago by the Kremlin or simply lost his will to fight. Perhaps it doesn’t matter—the Russian state can be quite skilled in finding in nearly everyone the magic, yet varying, point between cooptation and coercion. Sergei Zheleznyak, deputy speaker of parliament from the pro-Kremlin United Russia party, nicely summed up the official line last month, saying that the events of May 6 were “financed from abroad, so as to motivate those people who were headed to a provocation.” With the two cases now combined, the dramatis personae are set: The May 6 defendants will be cast as the foot soldiers of a would-be putsch, with Udaltsov, in his scheming with foreigners, playing a role loosely modeled on Trotsky’s.

Before the trial has a chance to display the martyrs of May 6, word of yet another possible twist is circulating in protester circles: Perhaps the very clashes with police at the heart of the indictment were manufactured, or at least egged on, by the state.

A self-appointed “independent public commission” made up of figures close the opposition released a 150-page report this spring that calls the violence of May 6 “a preplanned large-scale provocation.” In essence, the authors argue that rather than engaging in prosecutorial irregularities after the fact, the Putin state, just a day shy of restoring the leader to the presidency, arranged the whole affair.

Some pieces of the official story from May are indeed curious. For one, the Moscow police changed the approved route of the march at the last minute, and to this day the website of the Moscow police department shows a much different, and more expansive, map for the protest: marchers would be allowed to enter the park at Bolotnaya Square from all sides, including from the bridge that ended up being blocked by columns of riot police. That is the last information organizers had as they headed to the starting point of the demonstration. A police memorandum obtained by Reiter and posted by Russian Esquire, acknowledges that officials changed the location of barricades and police forces without informing organizers or the public

As it happened, metal barricades and rows of riot police blocked the bridge and one side of the park, pushing marchers into a tight stack on the bridge and funneling them toward the narrow embankment where clashes would later break out. And once the violence did kick off, the police may have been content to let it continue: Ilya Ponomoryev, one of the few Duma deputies to take part in opposition protests, told me that he tried unsuccessfully to talk with any police commanders that day about calming tensions between the two sides. When he found a vice mayor of Moscow off to the side, Ponomoryev said he was shooed off; the official told him, “What you wanted to create, this chaos, you got it.”

But chaos indeed seems the correct word to describe the events of May 6: Neither police officials or opposition leaders seemed fully in control. Moreover, even if the authorities increased tensions—perhaps on purpose—some people from the crowd did indeed attack police. Video taken on May 6 and leaked from law-enforcement sources to the state-run channel NTV depicts several defendants, including Barabanov, grabbing and punching several officers.2 (NTV is often an untrustworthy outlet of state propaganda, but the footage itself seems legit.) I watched the clips one night with Reiter. “They answered force with force,” she said of the protestors on May 6. “Police started to beat them, they started to answer, it’s that simple.” To deny that fact, she said, is an “affront,” even to those accused. In April, investigators released a page of Zimin’s diary, written on May 2, in which he describes his plans to meet with fellow anarchists a few days later at the May 6 protest for a “decisive moment.” He writes, “Burning fuel flying, smoke, and a blow to the face—this will be the last I remember before falling on the asphalt.” (Zimin's lawyers say this was a piece of creative writing.)

For the government, there's a benefit to associating anti-Putin activism with a rosters of who can easily be portrayed as oddballs—someone who's been declared insane, someone who stutters, someone who braids dreadlocks: just the kind of people you could tar as misfits who fight with cops without justification. (Other defandants, who include college students and office workers, might be harder to smear in this particular way.) But in any event, raising reasonable questions about the actions of at least some of the May 6 accused is not a way of answering questions about what measures investigators used to pursue the charges, or what sentences are justified. Prosecutors have never looked into the many charges of excessive force on the part of the police; Gaskarov, who was beaten in the face by police on May 6 and then arrested in April, was one of those who lodged a complaint that went nowhere.3 Same goes for 68 year-old pensioner who suffered a concussion after being struck in the head by police batons.

It doesn’t matter. Once the state put forward the narrative of “mass riots,” police were instantly exculpated of any wrongdoing. In other words, only the Kremlin can explain why it is trying to position chaotic street clashes with police one afternoon in May more than a year ago as a premeditated attempt at a coup’detat.

Not long ago, I went to see Viktor, Savelov’s father, at their three-room apartment in the northern outskirts of Moscow. He showed me childhood photos of his son and told me of their trips to the Russian Far East, where they would walk along the river gathering stones. In the corner of Savelov’s bedroom, beyond the Pam Anderson poster and the Warcraft CDs, was a large, empty aquarium. “I gave all the fish away,” his father said. He opened the closet door to show me a messy stack of papers he scooped up from the floor after the police came. “He’ll come home one day and figure it all out,” Viktor said.

The full 40-minute documentary can be seen in Russian here; the footage of Udaltsov is shown between 10–13 minutes.

The footage of Barabanov starts at minute 18:15 and continues for the next 44 seconds.

Footage of Gaskarov being beaten by police is on Youtube.