Opioids like oxycodone and methadone have been prescribed for pain relief since the early 1900s. But the rise of these painkillers, most notably Oxycontin, as a panacea treatment for chronic pain in the past two decades has been costly. Dr. Barth Wilsey, a physician specializing in chronic pain at the University of California Davis Medical Center, has watched their growth with increasing concern. Although he recalls only one patient death in his 17-year career, it's not an uncommon way to go: In 2010, 22,134 people died from prescription drug overdoses, a number that has quadrupled since 1999.

“In my perspective,” says Wilsey, “we've got to look for something else.”

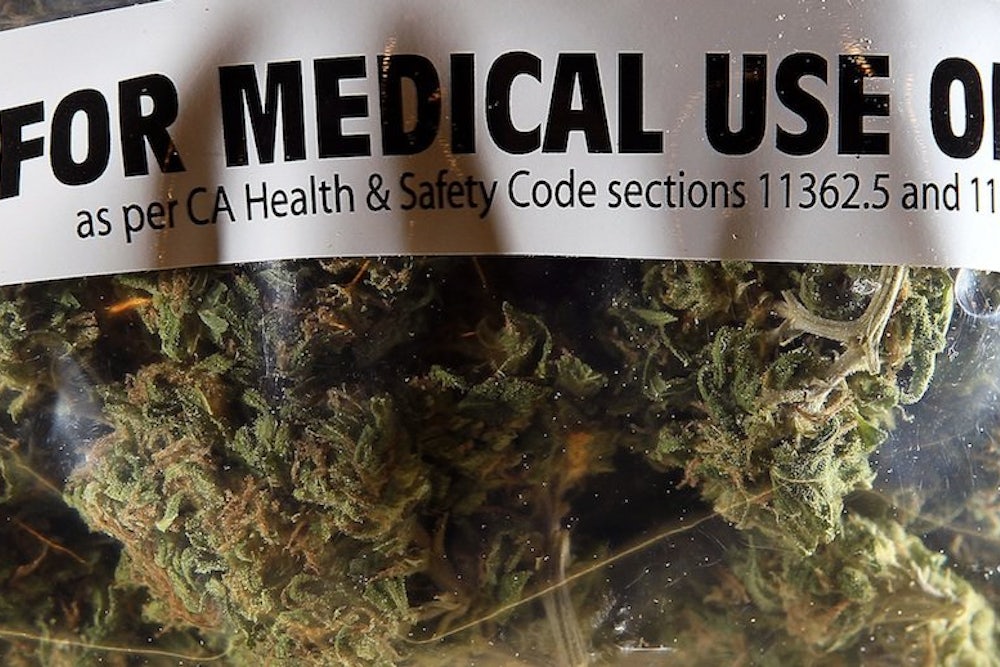

Wilsey is trying. He's leading a clinical trial at UC Davis that will test the effectiveness of cannabis—the preferred medical term for medical marijuana—on patients suffering from spinal cord injuries. It's a small but important step forward in a field of medicine that has seen little progress in this country.

Even as states charge forward on patients’ right to cannabis, the federal government clings stubbornly to the position that cannabis is only a drug of abuse—that there simply isn't enough science to justify its application as medicine.

“There is only no science because nobody allows you to do the research,” says Donald Abrams, a cancer and integrative medicine specialist at the University of California's Osher Center for Integrative Medicine.

Abrams began his medical career at ground zero of the AIDS crisis: San Francisco, in 1977. By the mid-'80s he had become assistant director of San Francisco General Hospital's AIDS program, and a rising star internationally. It was well known and generally accepted amongst his colleagues that patients used marijuana to help stimulate appetite and relieve pain. One of the hospital's most popular volunteers was “Brownie” Mary Jane Rathbun, so-named for the pot brownies she distributed on the ward.

In 1992, Abrams was at the International AIDS conference in Amsterdam when a CNN broadcast on a hotel lobby television caught his eye. To his surprise, there was Rathbun, being led out of his hospital in handcuffs. When Abrams returned to California there was a letter on his desk from Rick Doblin, director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies.

Doblin founded the non-profit in 1986 to help scientists design, fund, and obtain approvals for studies on illicit drugs. He had been interested in a marijuana trial for some time. If MAPS provided the initial funding, proposed Doblin, would Abrams serve as lead investigator on a clinical trial looking at the effects of cannabis on those with AIDS and HIV?

“Doblin threw down the gauntlet and I took it up,” Abrams said. “I had no idea what I was getting into.”

It would turn out to be the worst experience of his career.

Any clinical trial testing substances on human subjects requires two things to go ahead. First, the trial protocol—a detailed plan for its execution—must be approved by an academic review board. Second, the protocol needs approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

But cannabis is unique in that it requires an additional level of approval for clinical study, from a review board of federal scientists appointed by NIDA and Human Health Services. NIDA is the sole provider of research-grade cannabis. The plant material itself comes from a contracted grower—a facility at the University of Mississippi, whose 12-acre garden plot is the only marijuana field in the country that federal agents can't touch.

It's been this way since 1968, when the facility was first licensed by the Drug Enforcement Agency to serve two main purposes: testing the potency of marijuana seized from the illegal market, and growing and distributing product—typically in the form of pre-rolled, freeze-dried marijuana cigarettes—for federally-approved research projects.

For Doblin’s 1992 study on the effects of cannabis on AIDS patients, MAPS funded the development of the trial protocol, the detailed plan for its organization and execution. It took another year to get the protocol approved by the appropriate institutions: the FDA, the California research advisory panel, and the University of California's review board.

The final step was applying to the National Institute of Drug Abuse for the cannabis to conduct the study. Abrams waited nine months for a response, which came in the form of a brief rejection letter from then-director Dr. Alan Leshner. No approval, no cannabis, no study.

Abrams was incensed. He wrote a letter, picking apart NIDA's critiques of the protocol and reminding Leshner that the proposed trial already had ample institutional support. “You and your Institute failed,” concluded Abrams. “In the words of the AIDS activist community: SHAME!”

Although today NIDA maintains that it “has and will continue to support research on both the adverse effects, and therapeutic uses for marijuana provided the research applications meet accepted standards of scientific design,” historically it has funded studies focused only on the potential harmful effects of the drug.

Other centers and institutes within the National Institutes of Health have funded research on the medicinal properties of cannabis, most of which was funnelled through the California-based Center for Medical Cannabis Research throughout the 2000s.

The Center was founded in 1999 with $8.7 million dollars appropriated by the state legislature. This came on the heels of Proposition 215, which allowed California patients access to medical marijuana on a doctor's advice; the first such legislation in the country.

Prop 215 ushered in a kind of golden age of cannabis research, of which the center was a huge part. It provided invaluable support to researchers, helping them navigate the maze of regulatory requirements for cannabis.

“We were really well-funded,” says Igor Grant, the center's director. “We went to Washington, talked to federal officials, indicated what the center was all about. I think they were reassured.”

NIDA would eventually provide cannabis for 13 studies funded by the center, including two in which Abrams served as head investigator. By 2009, the center had run through its initial allotment of funding, and currently, there is no more on the table. Although it still exists as a resource, it is no longer supporting new trials. Without that institutional support, says Abrams, “research has fled.”

“There's just not a lot of incentive to study cannabis,” he says. “It's very difficult to do.”

No one knows this better than Doblin. Following the failed AIDS trial, Doblin and MAPS made three more attempts to conduct clinical trials using cannabis, all of which have failed.

The last was in 2010, when MAPS sponsored a trial looking at cannabis as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. It would involve 50 veterans and five different potencies of smoked or vaporized marijuana, or placebo.

The HHS and NIDA board denied the PTDS protocol, citing, among other things, safety concerns for “drug-naive participants” and a lack of research expertise on the part of the principal investigator, Dr. Sue Sisley.

The decision garnered a significant amount of bad press, especially given that PTSD sufferers comprise the largest patient group in Arizona's medical cannabis program.

Sisley charged that the decision was politically, not scientifically, motivated.

"The doctors I know think this war on marijuana is awful, and they're tired of being in the middle of it," she told The Atlantic. "They just want to do real research, or read real research, and not operate around all of these agendas."

Doblin wasn't a bit surprised. In fact, he already had other irons in the fire. In 2001, Doblin had convinced Dr. Lyle Craker, a professor of plant medicine at the University of Massachusetts to apply to the Drug Enforcement Agency for his own license to grow and cultivate marijuana under contract to MAPS—thereby circumventing the National Institute of Drug Abuse altogether.

Despite letters of support, including from senators Ted Kennedy and John Kerry, the DEA denied Craker's application. Following an unsuccessful 2005 lawsuit to try and force the DEA's hand in the matter, the case has languished in appeals courts ever since.

Despite his history with NIDA and the DEA, Doblin remains optimistic. Last February saw the introduction of two separate bills in Congress that would allow the states to establish cannabis policies without interference from the feds.

“I think it's inevitable that marijuana will become a prescription medicine,” says Doblin. “It's just a question of how long we're going to fight it out as a society.”

The fact that the National Institute of Drug Abuse is funding Barth Wilsey's study is significant. It's the only trial looking at the potential benefits of cannabis in the institute's funding history.

With funding direct from NIDA, Wilsey didn't have to submit his protocol to Human Health Services for approval, eliminating an extra burden of bureaucracy and making for “relatively smooth sailing,” he says.

Wilsey believes one of the reasons his study was funded is because—unlike Doblin—he is looking at a low-THC strain of cannabis, a product that would be presumably less susceptible to diversion by criminal interests. This is intentional, he says, to serve the best needs of his patients. Many are middle-aged, and uninterested in the psychedelic side effects of cannabis.

What they do want is relief. And right now, only about half of his patients can find that with conventional prescription drugs.

“The science is becoming more robust, and I think we're going to see more funding,” he says. “As a pain-management therapy, cannabis is effective.”

Colleen Kimmett is a Vancouver-based journalist who writes about energy, the environment and sustainable cities.