On July 1, interest rates on a key federal student loan are set to double, and, for once, the White House and House Republicans might reach a compromise to avoid the hike. Unfortunately, students might be better off if they didn't: Many activists say they'd prefer no deal at all to the one on the table. Short-term patches have become routine in a Washington seemingly incapable of permanent solutions, but in this case a patch may be the answer. On student loans, the best thing to come of the next four weeks would be a measure that buys more time.

The administration and House Republicans agree that the interest rate on loans—including but not limited to the most common variety, Stafford Loans, which face the July 1 increase—should rise and fall with the economy instead of being set at a fixed rate by Congress, as things currently stand. House Democrats lowered the rate on subsidized Stafford Loans to its current level of 3.4 percent in 2008, intending it to be a temporary measure; unsurprisingly, it was too popular to do away with easily, and now Democrats and Republicans fight almost annually over how to adjust it. Both the Obama administration and House Republicans propose a "variable interest rate approach," which would peg the student loan rate to the performance of the ten-year Treasury Note, plus a few percentage points. “When you start out with the fact that the president himself talked about a variable interest rate approach, and the House talked about a variable interest rate approach, it appears to me we’re quibbling about details,” said Richard Vedder of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity.

Here's the problem from the student debtors' perspective: The president's plan doesn't cap the rates, which means they could spike to unprecedented heights as the economy recovers. (Right now, the ten-year note pays interest at around two percent, but before the recession it was closer to five. Even at that unremarkable level, figuring in the president's "add-on"—which would put the rate 0.93 to 3.93 percentage points above that of the ten-year note, depending on the type of loan—pushes students nearly to or over the dreaded 6.8 percent fixed rate.) The plan that passed the House last week, written by Representative John Kline, caps rates at a steep 8.5 percent. (Keep in mind that the current rate has already produced record levels of delinquincy—the Department of Education announced last week that 11 percent of loans were 90 days or more past due.) Student advocates are grumbling that they’ll be better off in the long run if the rate doubles. A flat 6.8 percent rate beats hitting an 8.5 percent ceiling—or not having a ceiling at all.

Preferring uncertainty to an irremediably bad accord, students—and some leading Democrats—are pinning their hopes on what looks, at the outset, like the least ambitous bill in the Senate: a two-year extension of the current rate. “Comprehensive student loan reform is going to take time and we have to get it right. We definitely cannot screw it up,” said Chris Lindstrom, Higher Education Program Director at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group. “Rallying around another short term fix doesn’t feel satisfying or like we’re really mustering the best solution to the problem, but I’ve quickly gotten over that feeling.”

Student groups have written letters to Obama expressing the same sentiment: Unless he's prepared to overhaul his proposal before July 1, they need more time to convince him that he should. "While the President’s budget keeps rates low in the near term, we’re disappointed that it risks sky-high interest rates in the long term... Without a cap, this proposal falls far short of the comprehensive reform to student loans that we need," the youth group Rock the Vote wrote in April. "We look forward to working with the President on a more tenable solution to keep rates low, be it a long-term solution that actually protects future borrowers, or a short-term action that allows time to develop a long term plan."

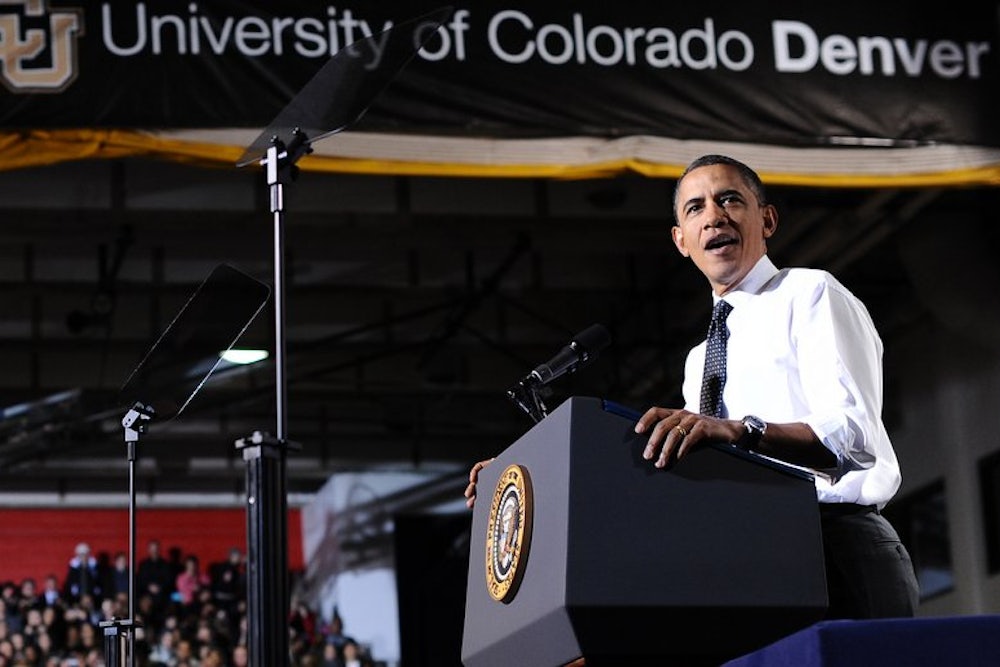

A compromise between the administration and House Republicans is still far from certain. Speaking in the White House Rose Garden Friday, flanked by college students, Obama dismissed the House bill. “I'm glad that the House is paying attention to it, but they didn't do it in the right way,” he said. In his plan, President Obama maintains a distinction between subsidized loans for needier borrowers and unsubsidized loans; the Republicans do not. Obama's plan sets the rate at the moment the loan is taken out so students aren't surprised by higher costs down the road; the House bill lets the rate float throughout the life of the loan. The administration advocates a “pay as you earn” provision to cap what students owe each month at 10 percent of their income. The Republican proposal would generate an estimated $3.7 billion in revenue over and above the $34 billion the government is already projected to make off loans next year, and the bill details that this money should go toward paying down the deficit. In the past, Obama (whose own proposal is designed to be budget neutral; no additional spending on, or revenue from, student loans) has directed profits from student loans into the Pell Grant program, and has spoken against applying them to the deficit. This may be one of the reasons he threatened to veto the House’s bill should it pass the Senate and end up on his desk in its current form.

Though far from perfect, the White House plan is "worlds apart from intentionally having a [student loans] program that generates money" for the rest of government, said Tobin Van Ostern of the Center for American Progress. He added that he suspects the President's "ideal policy stance" would infuse the loans program with more federal money to drive students' costs down, and the White House made its plan budget neutral instead of investing money because "I think their take was, 'This is as far as we can go over and have a realistic chance of Republicans coming onboard.'"

That political caluculation aside, Van Ostern said, "For youth groups, their point is they're not going to go for a deal that is worse for students than current law."

Senate Democrats have rallied around the idea that the best thing Washington can accomplish in the next four weeks is to buy itself more time. About a dozen of them have signed onto the extension bill, which was introduced by Majority Leader Harry Reid along with Senators Tom Harkin and Jack Reed, and which includes a list of tax loopholes that could be closed to pay for the estimated $8.3 billion cost.

Some of the senators pushing hardest for the extension also have further ranging plans. The most comprehensive is Reed’s; like the House and administration proposals, it ties interest rates to the economy, though at a lower rate (pegged to a lower-performing treasury note, the 91-day instead of the 10-year) and with a lower cap (6.8 percent for subsidized loans and 8.25 percent for unsubsidized, as opposed to Kline’s 8.5 percent across the board). Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, another proponent of the extension, put out a bill that would allow debtors with pre-existing loans to refinance them at a rate of 4 percent. The most-buzzed bill is Senator Elizabeth Warren’s, which would give students the same interest rate as banks: 0.75 percent. Matthew Chingos and Beth Akers at Brookings called Warren’s bill “a cheap political gimmick,” but others have cheered the contrast between big finance and struggling students.

But, in the Senate, the bills devoted to a far-sighted fix have taken a backseat to the push for the two-year extension, according to Van Ostern. “It’s the same people who have some of these longer plans in the Senate who have agreed they need a short term extension first,” he said. “The short term over there is getting more attention than the long term.”

And, since most of the Senate bills were proposed in just the past few weeks, they haven’t yet been scored by the Congressional Budget Office. Lindstrom believes they haven’t figured as seriously in the debate because it’s unclear what they will cost. “Maybe we would be in place where a good comprehensive reform package could pass by July 1 if all these bills had been out there in February,” she said.

Many senators are hoping to bake a longterm fix into the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, which expires at the end of 2013. “We plan on addressing this issue within the context of the [HEA],” a spokeswoman for Gillibrand said in an email, adding that they’re not shooting for the July 1 deadline. Some argue that it makes sense to roll the student loan debate into the broader conversation about tuition costs and federal money for grant programs that the HEA will spark.

“On the one hand, it does make general sense that big programmatic changes could be tackled as part of broader changes, where you have more pieces to work with,” Van Ostern said. “On the other hand, last year the Senate passed a one year fix, and that’s how we got here.”

Nora Caplan-Bricker is an assistant editor at The New Republic. Follow her @ncaplanbricker.