The first time I walked into a CrossFit gym, I saw a pregnant woman doing pull-ups. In the hallway, a freezer full of meat. Nearly everyone ate “paleo,” meaning they thrived on the diet of our cavemen ancestors. Members called the gym a “box,” a shabby garage with puke buckets and whiteboards instead of mirrors. At the end of the workout, everyone wrote their times, reps, and weights on the walls. “Don’t worry,” my coach said, “you will not be humiliated.”

Though CrossFit—which combines weightlifting, gymnastics, plyometrics, and sprints—thrives on its sense of community, most outsiders call it a cult. Its founder brags that “it can kill you.” At CrossFit Epic in Iowa City, if you miss a class, everybody knows. The guy squatting next to you becomes your friend; you’ll probably see him in town. “You WODing it up tonight?” he’ll ask, referring to the “workout of the day.” Everyone talks about the WODs like ex-girlfriends: “Kelly” and “Cindy” and “Barbara” and “Fran.” These WODs are “the Girls.” “Remember ‘Fran’? That bitch.”

One night, when everyone went to a bar called Joe’s Place, the lifting coach was smack-talking one of the female members. “You don’t like men?” he asked.

“Nope,” she said. “I’m a lesbian.”

“But can women do this?” He grunted and raised his Coors Light, then chomped the aluminum with his teeth. Blood sprayed. I got it on my hand. He tried to high-five me.

“You have blood on your shirt,” I told him.

“I don’t have blood on my shirt,” he said. “I’ve got shirt on my blood!”

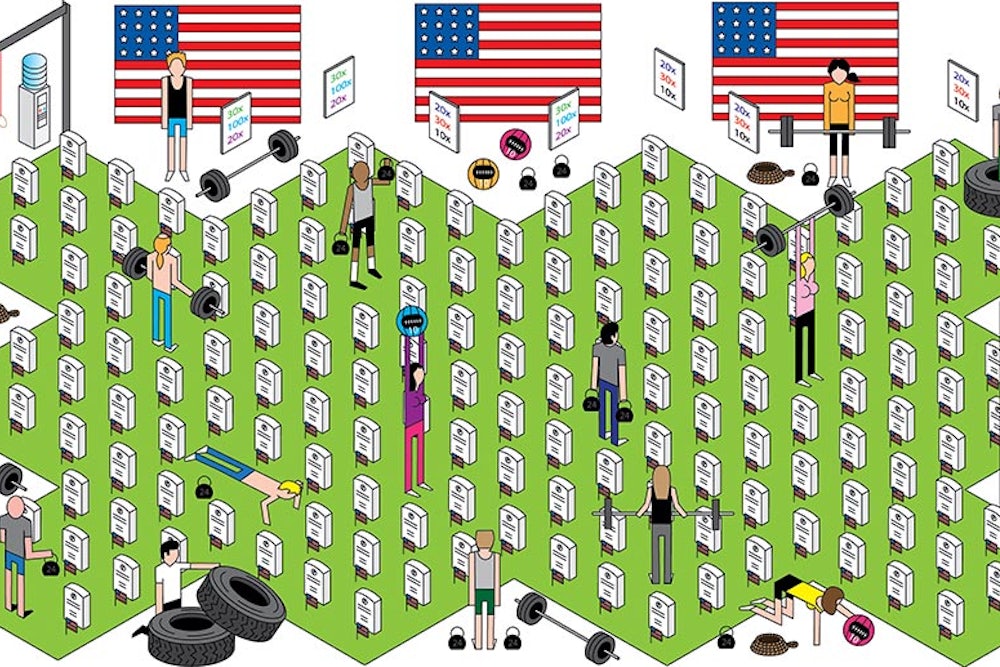

There’s a militaristic strain to each WOD, a boot-camp quality that makes each rep feel as if something’s at stake besides hip fat or glute strength. The coach is always circling, yelling, commanding you to never drop that bar. Burpees are compared to the movements you might make in combat before you engage the enemy and sprint 30 yards to save your wounded friend. Today, these military-style workouts (P90X, Tough Mudder, SEALFit) are commonplace alternatives to the gym. Marines train with CrossFit, but so do soccer moms. It’s this militarization, this puke-inducing exertion, that keeps me coming back—and that occasionally startles me with its politics.

About a month after I started training, I found a WOD called “Victoria” on the schedule. A young woman came up to me, pointed at the board where the WOD was written out in green sharpie, and told me the 27 kettlebell swings we were about to do represented the number of children shot by Adam Lanza.

The “Victoria” in question was Victoria Soto of Sandy Hook Elementary. At the time, I was not aware of the popular CrossFit tradition of working out to memorialize dead American heroes—soldiers, mostly, but also firefighters, cops, even teachers. Martin Richard, the eight-year-old victim of the Boston Marathon bombings, was given his own WOD.

Here’s what “Victoria” looks like: 5 rounds as fast as you can of 10 thrusters, 12 sumo deadlift high pulls, 14 box jumps, 12 burpees, 27 kettlebell swings.

The numbers originate from the following facts: Victoria was a teacher for five years. She was gunned down in room 10 on 12/14/12, and she was 27 years old.

The woman’s theory about the dead children wasn’t correct, but what happened in Victoria’s class haunted me throughout the workout. I imagined the moments before she was shot, the lesson she was teaching, and the way she comforted the children. Across from me, six men with their shirts off grunted and threw down their weights. Were all of them remembering Victoria, too?

By the end of “Victoria,” I felt a bit troubled, if not used. I didn’t understand what we were all doing there in a factory gym, sweating and mourning. Is this where we go to honor our dead? But mostly I was exhausted. I cupped my stomach and ran to the bathroom. One guy curled himself between barbell plates. Another flopped a little bit like a fish. We never did “Victoria” again. It was too hard. People complained. That woman continued to think 27 represented the number of dead children at Sandy Hook. “I hate ‘Victoria,’ ” she said.

The idea of a “Hero WOD” is this: You’re alive and they’re dead. So, while you complete the workout, you think of them, and you ignore your pain, because you should be happy that you’re able to experience any pain at all.

The lifting coach raised his Coors Light, then chomped the aluminum with his teeth.

All Hero WODs come with an obituary and are conceived with maximal physical suffering in mind. The tradition began in 2005, after the Taliban ambushed and killed three Navy SEALs in the Hindu Kush. One of the fallen soldiers, Lieutenant Michael Murphy, was a CrossFitter, and his favorite workout was one he designed for himself—one-mile run, 100 pull-ups, 200 push-ups, 300 squats, one-mile run. When Murphy was alive, he called it “Body Armor.” When he died, it became a Hero WOD, and it’s now a tradition to perform “Murph” on Memorial Day.

Russell Berger of CrossFit Huntsville, a frequent contributor to CrossFit Journal, says that, if you take the time to learn about the soldiers (there are more than 100 Hero WODs), then the psychological effects of performing the workouts are tremendous. “When the pain of pushing harder becomes too great,” Berger writes, “I am reminded of the sacrifice these men made for my freedom, and my struggle becomes laughable. And when I compare my temporary suffering to the lifelong sorrow felt by the grieving families of these men, dropping the bar becomes an embarrassment to my country.”

Staff Sergeant Brendan Souder submitted a Hero WOD proposal to honor his friend Corporal Ryan McGhee, who was fatally wounded by small-arms fire in Iraq. “Every time you do that workout, you try to think about what it was like to be in that guy’s shoes,” he told Berger. “Everything up until the point he died.”

CrossFit Journal collects videos of gyms performing Hero WODs, and after my experience with “Victoria,” I decided to watch one in which a marine corporal named Aaron Mankin told a story to a room full of CrossFitters about the day in Iraq that he caught on fire.

Mankin was in a 26-ton amphibious assault vehicle that rolled over an improvised explosive device. The vehicle—full of marines, chow, and ammunition—shot ten feet in the air. The six men to his right were dead. His uniform was on fire. His face was on fire. Mankin slipped out of the top-hatch, dove into a ditch, and tried to extinguish the flames, but only managed to set everything around him on fire. He gave up, closed his eyes, and waited to die. Grenades in the vehicle exploded. Ammo exploded. Mankin thought he heard the dying sounds of trapped marines. He got up and stumbled for them, thought of pulling them from the hatch, and he was close, but another corporal grabbed him by the collar and dragged him to a rescue chopper.

The fire took Mankin’s ears and half of his nose. He lost two fingers on his right hand. A seared throat means he will forever speak in struggled gasps.

“The more you sweat in peace,” Mankin told the crowd, “the less you bleed in war.”

In the video, standing next to Mankin, waiting for his turn at the microphone, was another veteran, unnamed, but also nearly burned alive. The fire mangled his nose and mouth and ears, and left him hairless. Unlike Mankin, who underwent reconstructive plastic surgery and now, eight years after the fire, has two ears, a nose, handsome blue eyes, and expressive brows, this unnamed veteran had no evidence of life before war. And there he was, at a CrossFit gym, hoping to teach a crowd of civilians how to grieve for the individuals lost to our foreign wars.

A full U.S. Marine Corps Color Guard entered. Hands raised to hearts. A woman sang the National Anthem.

“So if you sweat here today,” Mankin said, “if you are willing and able, I ask: What will you do? Will you do something? Will you do anything? For the man in uniform! For the ones who give so much. What can you give?”

The camera zoomed in on several women, red-faced and weeping. Other CrossFitters joined. The mourning had already begun.

The mic fluttered between Mankin’s three fingers, and with an airy voice he exclaimed, “Enjoy your workout!” Everyone then moved into position, ready to fight their own war in the box.

Jennifer Percy is the author of Demon Camp: A Soldier’s Exorcism (Scribner, January 2014).