The sewing machine was the smartphone of the nineteenth century. Just skim through the promotional materials of the leading sewing-machine manufacturers of that distant era and you will notice the many similarities with our own lofty, dizzy discourse. The catalog from Willcox & Gibbs, the Apple of its day, in 1864, includes glowing testimonials from a number of reverends thrilled by the civilizing powers of the new machine. One calls it a “Christian institution”; another celebrates its usefulness in his missionary efforts in Syria; a third, after praising it as an “honest machine,” expresses his hope that “every man and woman who owns one will take pattern from it, in principle and duty.” The brochure from Singer in 1880—modestly titled “Genius Rewarded: or, the Story of the Sewing Machine”—takes such rhetoric even further, presenting the sewing machine as the ultimate platform for spreading American culture. The machine’s appeal is universal and its impact is revolutionary. Even its marketing is pure poetry:

On every sea are floating the Singer Machines; along every road pressed by the foot of civilized man this tireless ally of the world’s great sisterhood is going upon its errand of helpfulness. Its cheering tune is understood no less by the sturdy German matron than by the slender Japanese maiden; it sings as intelligibly to the flaxen-haired Russian peasant girl as to the dark-eyed Mexican Señorita. It needs no interpreter, whether it sings amidst the snows of Canada or upon the pampas of Paraguay; the Hindoo mother and the Chicago maiden are to-night making the self-same stitch; the untiring feet of Ireland’s fair-skinned Nora are driving the same treadle with the tiny understandings of China’s tawny daughter; and thus American machines, American brains, and American money are bringing the women of the whole world into one universal kinship and sisterhood.

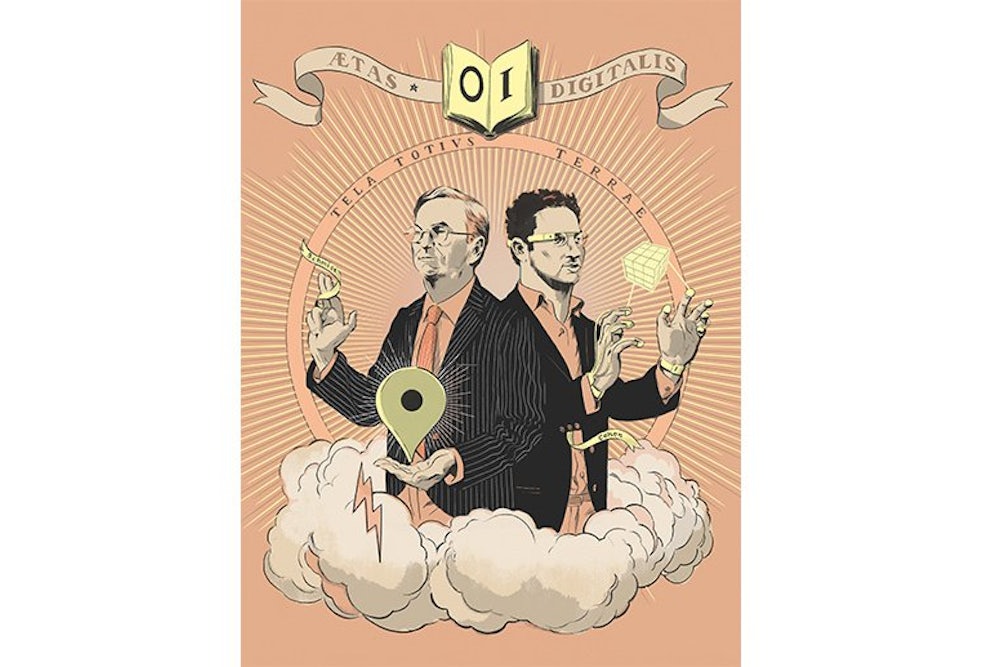

“American Machines, American Brains, and American Money” would make a fine subtitle for The New Digital Age, the breathless new book by Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, and Jared Cohen, the director of Google Ideas, an institutional oddity known as a think/do-tank. Schmidt and Cohen are full of the same aspirations—globalism, humanitarianism, cosmopolitanism—that informed the Singer brochure. Alas, they are not as keen on poetry. The book’s language is a weird mixture of the deadpan optimism of Soviet propaganda (“More Innovation, More Opportunity” is the subtitle of a typical sub-chapter) and the faux cosmopolitanism of The Economist (are you familiar with shanzhai, sakoku, or gacaca?).

There is a thesis of sorts in Schmidt and Cohen’s book. It is that, while the “end of history” is still imminent, we need first to get fully interconnected, preferably with smartphones. “The best thing anyone can do to improve the quality of life around the world is to drive connectivity and technological opportunity.” Digitization is like a nicer, friendlier version of privatization: as the authors remind us, “when given the access, the people will do the rest.” “The rest,” presumably, means becoming secular, Westernized, and democratically minded. And, of course, more entrepreneurial: learning how to disrupt, to innovate, to strategize. (If you ever wondered what the gospel of modernization theory sounds like translated into Siliconese, this book is for you.) Connectivity, it seems, can cure all of modernity’s problems. Fearing neither globalization nor digitization, Schmidt and Cohen enthuse over the coming days when you “might retain a lawyer from one continent and use a Realtor from another.” Those worried about lost jobs and lower wages are simply in denial about “true” progress and innovation. “Globalization’s critics will decry this erosion of local monopolies,” they write, “but it should be embraced, because this is how our societies will move forward and continue to innovate.” Free trade has finally found two eloquent defenders.

What exactly awaits us in the new digital age? Schmidt and Cohen admit that it is hard to tell. Thanks to technology, some things will turn out to be good: say, smart shoes that pinch us when we are running late. Other things will turn out to be bad: say, private drones. And then there will be lots of wishy-washy stuff in between. These indeterminate parts are introduced with carefully phrased sentences: “despite potential gains, there will be longer-term consequences,” “not all ... hype ... is justified ... but the risks are real,” and so on. To their credit, Cohen and Schmidt know how to hedge their bets: this book could have been written by a three-handed economist.

Other important changes lie ahead. First, a “smart-phone revolution,” a “mobile health revolution,” and a “data revolution” (not to be confused with the “new information revolution”) are upon us. Second, “game-changers” and “turbulent developments” will greet us at every turn. Your hair, for example, will never be the same: “haircuts will finally be automated and machine-precise.” Anyone who can contemplate ideas this bold deserves immediate admission into the futurist hall of fame. The other good news from the future—try this after a night out—is that “there will be no alarm clock in your wake-up routine [because] you’ll be roused by the aroma of freshly brewed coffee.” It’s a grim future for tea-drinkers—but what can the poor saps do? “Technology-driven change is inevitable.” Except, of course, when it isn’t (“you cannot storm an interior ministry by mobile phone”); but that, too, is perhaps a matter of time.

The goal of books such as this one is not to predict but to reassure—to show the commoners, who are unable on their own to develop any deep understanding of what awaits them, that the tech-savvy elites are sagaciously in control. Thus, the great reassurers Schmidt and Cohen have no problem acknowledging the many downsides of the “new digital age”—without such downsides to mitigate, who would need these trusted guardians of the public welfare? So, yes, the Internet is both “a source for tremendous good and potentially dreadful evil”—but we should be glad that the right people are in charge. Uncertainty? It’s inevitable, but manageable. “The answer is not predetermined”—a necessary disclaimer in a book of futurology—and “the future will be shaped by how states, citizens, companies and institutions handle their new responsibilities.” If this fails to reassure, the authors announce that “most of all, this is a book about the importance of a guiding human hand in the new digital age.” The “guiding hand” in question will, in all likelihood, be corporate and wear French cuffs.

The original concepts introduced in The New Digital Age derive their novelty from what might be described as the two-world hypothesis: that there is an analog world out there—where, say, people buy books by Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen—and a matching virtual world, where all sorts of weird, dangerous, and subversive things might happen. Or, as the authors themselves put it, “one [world] is physical and has developed over thousands of years, and the other [world] is virtual and is still very much in formation.“ As “the vast majority of us will increasingly find ourselves living, working and being governed in two worlds at once,” new problems will emerge and demand original solutions.

Their unquestioned faith in the two-world hypothesis leads Cohen and Schmidt to repeat the old chestnut that there exists a virtual space free from laws and regulations. Their view of the Internet as “the world’s largest ungoverned space” was quite fashionable in the 1990s, but in 2013 it sounds a tad outdated. Consider their employer, Google. The company knows very well that, for all the talk of virtuality, it still has bank accounts that may be frozen and staffers who may be arrested. Just how good is it to be the king of the “world’s largest ungoverned space” if your assets and employees are still hostage to the whims of governments in physical space? Does anyone at Google really believe in the existence of “an online world that is not truly bound by terrestrial laws”? Where is that world, and if it exists, why hasn’t Google set up shop there yet? How come Google keeps running into so much trouble with all those pesky “terrestrial laws”—in Italy, India, Germany, China? Next time Google runs afoul of someone’s “terrestrial laws,” I suggest that Cohen and Schmidt try their two-world hypothesis in court.

Cohen and Schmidt argue—without a hint of irony—that “the printing press, the landline, the radio, the television, and the fax machine all represent technological revolutions, but [they] all required intermediaries. ... [The digital revolution] is the first that will make it possible for almost everybody to own, develop and disseminate real-time content without having to rely on intermediaries.” Presumably we will disseminate “real-time content” brain to brain, because that is the only way to avoid intermediaries. Coming from senior executives of the world’s most powerful intermediary—the one that shapes how we find information (not to mention Google’s expansion into fields like fiber networks)—all this talk about the disappearance of intermediaries is truly bizarre and disingenuous. This may have been more accurate in the 1990s, when everyone was encouraged to run their own e-mail server—but the authors appear to have missed the advent of cloud computing and the subsequent empowerment of a handful of information intermediaries (Google, Facebook, Amazon). Not surprisingly, Cohen and Schmidt contradict their own gospel of disintermediation when they mention just how easy it was to weaken WikiLeaks by going after companies such as Amazon and PayPal.

In the simplicity of its composition, Schmidt and Cohen’s book has a strongly formulaic—perhaps I should say algorithmic—character. The algorithm, or thought process, goes like this. First, pick a non-controversial statement about something that matters in the real world—the kind of stuff that keeps members of the Council on Foreign Relations awake at their luncheons. Second, append to it the word “virtual” in order to make it look more daring and cutting edge. (If “virtual” gets tiresome, you can alternate it with “digital.”) Third, make a wild speculation—ideally something that is completely disconnected from what is already known today. Schmidt and Cohen’s allegedly unprecedented new reality, in other words, remains entirely parasitic on, and derivative of, the old reality.

The problem is that you cannot devise new concepts merely by sticking adjectives on old ones. The future depicted in The New Digital Age is just the past qualified with “virtual.” The book is all about virtual kidnappings, virtual hostages, virtual safe houses, virtual soldiers, virtual asylum, virtual statehood, virtual multilateralism, virtual containment, virtual sovereignty, virtual visas, virtual honor killings, virtual apartheid, virtual discrimination, virtual genocide, virtual military, virtual governance, virtual health-insurance plans, virtual juvenile records, and—my favorite—virtual courage. The tricky subject of virtual pregnancies remains unaddressed, but how far away could they be, really?

In the new digital age, everything—and nothing—will change. The word “always” makes so many appearances in this book that the “newness” of this new age can no longer be taken for granted: “To be sure, governments will always find ways to use new levels of connectivity to their advantage”; “Of course, there will always be the super-wealthy people whose access to technology will be even greater”; “there is always going to be someone with bad judgment who releases information that will get people killed”; “there will always be some companies that allow their desire for profit to supersede their responsibility to users”; “the logic of security will always trump privacy concerns”; “To be sure, there will always be truly malevolent types for whom deterrence will not work.” Always, always, always: the new digital future sounds very different, except that it isn’t.

But even this permanence is not to be taken for granted, because the new digital age is itself a plethora of ages. It is “an age of comprehensive citizen engagement,” “an age of state-led cyber war,” “an age of expansion,” “an age of hyper-connectivity,” “the age of digital protests,” “the age of cyber terrorism,” “the age of drones,” and—who would have thought?—“the age of Facebook.” Unable to decide just how fluid or permanent today’s world is, Schmidt and Cohen leave their pinching shoes and automated haircuts behind and deliver some more serious predictions. Most of them fall into two categories: first, speculation on the truly bizarre stuff that looks legitimate only because of the authors’ belief in the two-world hypothesis, and, second, speculation on perfectly normal stuff that is hardly new, and thus needs no prophets. (What better way to secure one’s reputation as a futurist than to predict something that has already happened?)

The first category is full of seemingly provocative insights that self-deflate after a second of analysis. Consider just one sub-family of their “virtual”

concepts: “virtual sovereignty,” “virtual statehood,” “virtual independence.” What are they good for exactly? This is how the authors explain it:

Just as secessionist efforts to move toward physical statehood are typically resisted strongly by the host state, such groups would face similar opposition to their online maneuvers. The creation of a virtual Chechnya might cement ethnic and political solidarity among its supporters in the Caucasus region, but it would no doubt worsen relations with the Russian government, which would consider such a move a violation of its sovereignty. The Kremlin might well respond to virtual provocation with a physical crackdown, rolling in tanks and troops to quell the stirrings in Chechnya.

For a start, this paragraph exposes Schmidt and Cohen’s lack of familiarity with the conflict. The Chechen rebels and their media outlets do operate several websites. Indeed, the most prominent of them, such as the Kavkaz Center, were forced to move their servers across several countries to ensure that they could operate without too much interference by the Russian authorities, finally settling in Scandinavia. But just because the Chechnya of the rebels’ imagination has a website doesn’t mean that we are witnessing the “virtual Chechnya” of Schmidt and Cohen’s imagination. Even if Chechnya had its own domain name that the rebels could seize, it wouldn’t amount to much. The rebels have been seizing hostages in theaters and hospitals to little avail—and we are supposed to believe that they would gain considerable power by seizing trivial digital assets?

So what if the rebels can proclaim their “virtual independence”? As propaganda victories go, this is next to worthless. They might as well announce that, after decades of violent struggles, ordinary Chechens are finally free to breathe or to wink: not exactly a meaningful improvement in human freedoms. A declaration of “virtual independence” changes nothing geopolitically, not least because the Russian-Chechen conflict is, at the heart of it, a conflict about a piece of land—of physical reality. Unless that piece of land is secured, “virtual independence” is meaningless.

This is all rudimentary stuff, and anyone with the most perfunctory understanding of geopolitics could figure it out after a moment of careful reflection. But sober reflection is much less fun than wild speculation, and so Cohen and Schmidt—forgetting that the Chechen rebels have actually hosted their servers abroad for more than a decade—spin some futurology about Chechnya and Mongolia:

Supporters of the ... Chechen rebels might seek to use Mongolia’s Internet space as a base from which to mobilize, to wage online campaigns and build virtual movements. If that happened, the Mongolian government would no doubt feel the pressure from ... Russia, not just diplomatically but because its national infrastructure is not built to withstand a cyber assault.... Seeking to ... preserve its own physical and virtual sovereignty, Mongolia might find it necessary to abide by a ... Russian mandate and filter Internet content associated with hot-button issues. In such a compromise, the losers would be the Mongolians, whose online freedom would be taken away as a result of self-interested foreign powers with sharp elbows.

The poor Mongolians! But are there any grounds for concern? As already noted, several countries—mostly in Scandinavia—have been hosting the websites of Chechen rebels for a long time. Needless to say, Russia did not launch a war against them, and the Swedes and the Finns do not appear to have had their freedoms curtailed, either. Has the Kremlin been exerting pressure on these governments? Certainly—but this is how diplomacy has always worked. Why dabble in abstract futurology if experience and empirical data are readily available? But such evidence would undermine the idea that there is some special domain of politics called “the virtual,” where power works differently. The truth is that, video propaganda aside, digital platforms have been of little help to the Chechen rebels: no need to fantasize about Mongolia, just look at Chechnya.

Schmidt and Cohen’s book consistently substitutes unempirical speculation for a thorough engagement with what is already known. Take the prediction that we are about to witness the rise of “collective editing,” so that states will form “communities of interest to edit the web together, based on shared values or geopolitics.” Cohen and Schmidt give the example of ex-Soviet states becoming “fed up with Moscow’s insistence on standardizing the Russian language across the region” and joining together “to censor all Russian-language content from their national Internets and thus limit their citizens’ exposure to Russia altogether.” Scary stuff. What they omit to mention is that, technologically, nothing prevents Belarus or Armenia from doing most of those things already. So why haven’t they? Well, they might have missed the memo about the advent of the “new digital age.” More likely they know where their energy supplies and economic subsidies come from. The “virtual world” that Schmidt and Cohen extol does not in any way nullify or thoroughly transform the current geopolitical situation in which the ex-Soviet states find themselves. Sure, digital infrastructure has added a few levers here and there (and those levers can be used by all sides); but to argue that digital infrastructure has somehow created another world, with a brand-new politics and brand-new power relations and brand-new pressure points, is ridiculous.

The fact that most of what Cohen and Schmidt still predict for the future—from “virtual apartheid” to “virtual sovereignty”—has been technologically possible for a very long time is the best refutation of the two-world hypothesis. Nothing prevents a virtual government in exile from appointing a virtual minister of the interior who “would focus on preserving the security of the virtual state.” They can already do it today. But in the absence of material resources and a police force—the kinds of things that ministers of the interior have in the physical world—it would change nothing. The exchange rate between physical and virtual power is not one to one. Power relations do not much care for one’s ontological accounts of how the world is: with power, either you have it or you don’t.

This holds true regardless of how many worlds you posit. Imagine that tomorrow I announce the existence of a third world: forget “digital,” henceforth it’s all about “digital squared.” I then proceed to set up a search engine for that world: let’s call it Schmoogle. Then I proclaim that Schmoogle is the greatest thing since Google. (Google? These Luddites know nothing about “digital squared”!) I suspect that this clever little scheme will not make me rich, unless perhaps I publish a high-pitched manifesto—The New Digital Squared Age—to go along with it. This doesn’t mean that Schmoogle is doomed. What it means is that announcing that Schmoogle belongs to the revolutionary new world will get me nowhere. It is not enough to convince funders, users, and advertisers that the project has legs. One must actually create an entirely new age.

Why do so many of the trivial claims in this book appear to have gravitas? It’s quite simple: the two-world hypothesis endows claims, trends, and objects with importance—regardless of how inconsequential they really are—based solely on their membership in the new revolutionary world, which itself exists only because it has been posited by the hypothesis. Consider another claim from Schmidt and Cohen’s book: that “governments ... may go to war in cyberspace but maintain the peace in the physical world.” Something clearly isn’t right here. If governments are at war—a condition well-described in international law—then they are at war everywhere; as with pregnancy, one cannot be just a little bit “at war.” If governments engage in skirmishes that do not amount to war—a condition that is also well known to students of international law and politics—then they are not at war. It is certainly the case that increased connectivity has made it easier to engage in new skirmishes, but we are not dealing with anything even remotely revolutionary here. The banal truth buried in Schmidt and Cohen’s hyperbole is something like: governments can now mess up each other’s networks in much the same way that they mess up each other’s embassies. A revolution in global affairs it isn’t.

What do Cohen and Schmidt mean when they write that “just as some states leverage each other’s military resources to secure more physical ground, so too will states form alliances to control more virtual territory”? If we assume that “virtual territory” is a valid concept—a big if—this sounds truly horrifying. But on closer examination, all that Cohen and Schmidt are saying is that states will cooperate on technological matters—as they have done for centuries—and that this might have some repercussions for both military and non-military affairs. What is so refreshing about this insight? Or consider their prediction that the world will soon “see its first Internet asylum seeker.” Don’t tear up just yet: “a dissident who can’t live freely under an autocratic Internet and is refused access to other states’ Internets will choose to seek physical asylum in another country to gain virtual freedom on its Internet.” I have no doubt that someone might one day try this excuse—it would hardly be the oddest reason for requesting asylum—but would any reasonable government actually grant asylum on such grounds? Of course not. Once again, Schmidt and Cohen’s mechanical correspondence between the physical and the virtual confers upon the virtual—in this case, “virtual space”—a uniqueness it does not possess. If media censorship is a good enough reason to grant asylum, then all of China is eligible; after all, its newspapers, radio, and television are censored as heavily as its blogs. But try writing a book about “radio asylum seekers.”

So what exactly is new about the new digital age? Its perceived novelty—“unique” is a term especially beloved by Schmidt and Cohen—derives solely from their ability to conceal the theoretical emptiness of their use of the “virtual.” A more fitting title for this book would be The Somewhat New and Somewhat Digital Age.

But more than semantics is at stake here. The fake novelty is invoked not only to make wild predictions but also to suggest that we all need to make sacrifices—a message that is very much in line with Google’s rhetoric on matters such as privacy. “How much will we have to give up to be part of the new digital age?” ask Cohen and Schmidt. Well, if this age is neither new nor digital, we don’t need to give up very much at all.

The most annoying thing about this book is that it pays scant attention to already existing projects and technologies that Schmidt and Cohen see only as if in a vision. Consider this gem of a paragraph:

If you’re feeling bored and want to take an hour-long holiday, why not turn on your holograph box and visit Carnival in Rio? Stressed? Go spend some time on a beach in the Maldives. Worried your kids are becoming spoiled? Have them spend some time wandering around the Dharavi slum in Mumbai. Frustrated by the media’s coverage of the Olympics in a different time zone? Purchase a holographic pass for a reasonable price and watch the women’s gymnastics team compete right in front of you, live. Through virtual-reality interfaces and holographic-projection capabilities, you’ll be able to “join” these activities as they happen and experience them as if you were truly there.

I think we already have a technology for watching the Olympics: it’s called NBC. And, armed with a projector, a large screen, and 3-D glasses, you can already watch the women’s gymnastics team right in front of you. Perhaps, in the new digital age, you won’t have to turn off the lights. Three cheers for digitality! But is that it? As for that beach in the Maldives: don’t hold your breath. Even Wolf Blitzer—the world’s foremost connoisseur of holographs—is probably not wasting his evenings watching holographic sunsets in his living room. And as for the revolutionary parenting advice: who would possibly punish their spoiled kids with a holographic trip to India? Let’s have Schmidt and Cohen try it on their kids first.

Schmidt and Cohen dispatch their quirky examples in such large doses that readers unfamiliar with the latest literature on technology and new media might accidentally find them innovative and persuasive. In reality, though, many of their examples—especially those from exotic foreign lands—are completely removed from their context. It is nice to be told that innovators at the MIT Media Lab are planning to distribute tablets to children in Ethiopia, but why not tell us that this project follows in the steps of One Laptop Per Child, one of the most high-profile failures of technological utopianism in the last decade? Absent such disclosure, the Ethiopian tablet project looks much more promising—and revolutionary—than it actually is.

“Imagine the implications of these burgeoning mobile or tablet-based learning platforms for a country like Afghanistan,” Schmidt and Cohen declare. But it is actually not so difficult to imagine it, once the proper context has been established. Based on the track record of One Laptop Per Child, these learning platforms will be a waste of money. There is nothing wrong with making predictions, but when one opts to make predictions in the dark, unaided by what is already known about the present and the past, it is hard to take such predictions seriously. Why speculate, as Schmidt and Cohen do, about the positive role that social media and mobile phones could have played during the genocide in Rwanda, when we know the role that they played in the ethnic clashes in Kenya in 2007 and in Nigeria in 2010? Their role was far from positive.

Just a modicum of research could have saved this exercise in irresponsible futurology, but living in the future, Cohen and Schmidt do not much care about the present, which leads them likely to overstate their own originality. Thus they write glowingly of the many benefits that encryption will offer to NGOs and journalists, giving them the ability to report securely from different regions and thereby transforming journalism and human rights reporting. “Treating reporters in the same ways as confidential sources (protecting identities, preserving content) is not itself a new idea,” they proclaim, “but the ability to encrypt that identifiable data, and use an online platform to facilitate anonymous news-gathering, is only becoming possible now.” This reveals only how little they know about the world of reporters and NGO workers who actually work in places such as Burma, Iran, and Belarus. In 2003—a decade ago, an eternity in futurist time—Benetech, a nonprofit in California, launched open-source software called Martus, which does precisely what Cohen and Schmidt are fantasizing about: it allows journalists and NGO workers securely to add data to searchable and encrypted databases. Back in 2008, I saw such software used in the scrappy offices of an NGO that was tracking human-rights abuses in Burma from a remote location in Southeast Asia. For all their globe-trotting—they went to North Korea to see the future!—Cohen and Schmidt have a very poor grasp of what is happening outside Washington and Silicon Valley.

Schmidt and Cohen naively promise that, owing to the vast troves of information collected with “the technological devices, platforms and databases,” “everyone ... will have access to the same source material.” Thus, disputes over what happened in a war or some other conflict—interpretation itself—will become moot. A large claim—but where’s the evidence? I still remember the discussions about the war between Russia and Georgia in 2008. Yes, there was some interesting evidence—including from cell phones—floating around. But the same picture triggered completely different responses from Georgian bloggers and Russian bloggers: depending on what was depicted, one group was more likely to challenge the authenticity of the “source material.” More pictures—even if they do have the digital timestamps that excite Cohen and Schmidt—are not going to solve the authenticity problem. “People who try to perpetuate myths about religion, culture, ethnicity or anything else will struggle to keep their narratives afloat amid a sea of newly informed listeners,” they tell us. If so, we should try this in America one day: our own “sea of informed listeners”—informed about evolution, global warming, or the fact that Obama is not a Muslim—could be a pleasure to swim in.

In the same Panglossian vein, Schmidt and Cohen would rather spin fairy tales about the fantastic impact of new media on teenagers in the Middle East than engage with those teenagers on their own terms. “Young people in Yemen might confront their tribal elders over the traditional practice of child brides if they determine that the broad consensus of online voices is against it,” they announce. Perhaps. Alternatively, young people in Yemen might snap and share cell phone photos of their friends who have just been killed by drones. Connectivity is not a panacea for radicalization; all too often it is its very cause. Or are we supposed to believe that, in the new digital age, potential terrorists will opt for “virtual terrorism” and make spam instead of bombs?

Schmidt and Cohen are at their most shallow in their discussion of the radicalization of youth (which was Cohen’s bailiwick at the State Department before he discovered the glorified world of futurology). “Reaching disaffected youth through their mobile phones is the best possible goal we can have,” they announce, in the arrogant voice of technocrats, of corporate moguls who conflate the interests of their business with the interests of the world. Mobile phones! And who is “we”? Google? The United States?

The counter-radicalization strategy that Schmidt and Cohen proceed to articulate reads like a parody from The Onion. Apparently, the proper way to tame all those Yemeni kids angry about the drone strikes is to distract them with—ready?—cute cats on YouTube and Angry Birds on their phones. “The most potent antiradicalization strategy will focus on the new virtual space, providing young people with content-rich alternatives and distractions that keep them from pursuing extremism as a last resort,” write Cohen and Schmidt. For—since the technology industry

produces video games, social networks, and mobile phones—it has perhaps the best understanding of how to distract young people of any sector, and kids are the very demographic being recruited by terror groups. The companies may not understand the nuances of radicalization or the differences between specific populations in key theaters like Yemen, Iraq, and Somalia, but they do understand young people and the toys they like to play with. Only when we have their attention can we hope to win their hearts and minds.

Note the substitution of terms here: “we” are no longer interested in creating a “sea of newly informed listeners” and providing the Yemeni kids with “facts.” Instead, “we” are trying to distract them with the kinds of trivia that Silicon Valley knows how to produce all too well. Unfortunately, Cohen and Schmidt do not discuss the story of Josh Begley, the NYU student who last year built an app that tracked American drone strikes and submitted it to Apple—only to see his app rejected. This little anecdote says more about the role of Silicon Valley in American foreign policy than all the futurology between the covers of this ridiculous book.

When someone writes a sentence that begins “if the causes of radicalization are similar everywhere,” you know that their understanding of politics is at best rudimentary. Do Cohen and Schmidt really believe that all these young people are alienated because they are simply misinformed? That their grievances can be cured with statistics? That “we” can just change this by finding the digital equivalent of “dropping propaganda flyers from an airplane”? That if we can just get those young people to talk to each other, they will figure it all out? “Outsiders don’t have to develop the content; they just need to create the space,” Schmidt and Cohen smugly remark. “Wire up the city, give people basic tools and they’ll do most of the work themselves.” Now it’s clear: the voice of the “we” is actually the voice of venture capital.

And what of the almighty sewing machine? That great beacon of hope—described as “America’s Chief Contribution to Civilization” in Singer’s catalog from 1915—did not achieve its cosmopolitan mission. (How little has changed: a few years ago, one of Twitter’s co-founders described his company as a “triumph of humanity.”) In 1989 the Singer company, in a deeply humiliating surrender to the forces of globalization, was sold off to a company owned by a Shanghai-born Canadian that went bankrupt a decade later. American machines, American brains, and American money were no longer American. One day Google, too, will fall. The good news is that, thanks in part to this superficial and megalomaniacal book, the company’s mammoth intellectual ambitions will be preserved for posterity to study in a cautionary way. The virtual world of Google’s imagination might not be real, but the glib arrogance of its executives definitely is.

Evgeny Morozov is a contributing editor at The New Republic and the author, most recently, of To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism (PublicAffairs).