Frances says she’s twenty-seven all through the film, though she worries that people think she looks older. This is the anxiety of unstudied self-regard: for she does look a mite older, and Greta Gerwig, the actress doing Frances, is nearly thirty. As if to counter that dread state, Frances and Greta do all they can to act immature (so long as it’s whimsical and eccentric). They make Lena Dunham look like Hannah Arendt, and just in case you might think of a comparison to “Girls” yourself, Frances never takes her clothes off but behaves like Mary Pickford crossed with a middle linebacker. You may love her—you are meant to. You may reach for a hatchet and consider chopping off more than the last letters of “Halliday.” That’s how Frances Ha gets its title.

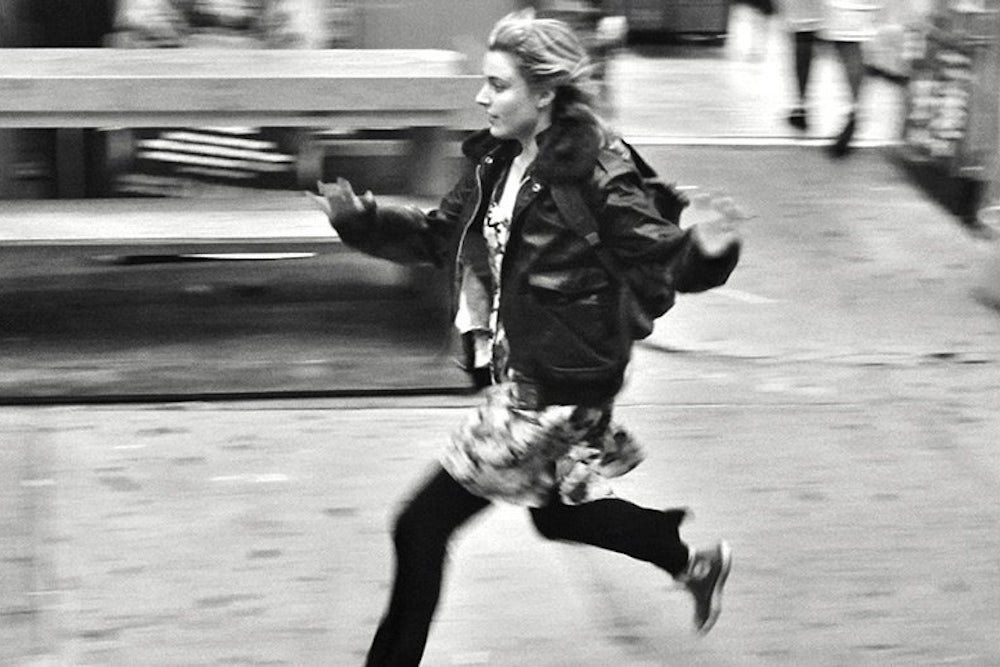

This is an odd film (creepier than it knows), and even if you feel the atmospheric company of Dunham-ism, with a little of Whit Stillman, Henry Jaglom, and Woody Allen, the core influence on Noah Baumbach’s film is fifty years older or more. Shot in real apartments and on the city streets of New York and Paris (with just a dash of Sacramento), and using a lovely digital black and white (filmed by Sam Levy, under the aura of the late Harris Savides, to whom the film is dedicated), with loose, casual camera movements, this is an homage to the French New Wave pictures of the early 1960s, no matter that its co-writers, Baumbach and Gerwig, were born after that bright dawn. So the movie uses bits of Georges Delerue music done for Truffaut (and it credits them at the end), but it knows this is a culture in which few will identify that echo. Not many people realized Michel Hazanavicius had stolen Bernard Herrmann music from Vertigo for The Artist. That’s a kind of theft or borrowing subsumed in the hopeful wisdom that no one will remember.

But even if you don’t know the New Wave films where some new director asked a young actress or a girlfriend to just walk around Paris, or photographed her forever or until he ran out of film, still Frances Ha is resolutely youthful. The story? Frances is what the movie calls “undateable.” She lives in New York in or out of other people’s apartments, out of work, but kidding herself that she is going to be a dancer with a modern company. Gerwig is appealing and lively, but she is not svelte or poised and shows no sign of being a dancer. The audience knows the company is a pipedream. She ends up working in the company’s office, but she has had a moment of fulfillment. Would her parents (in Sacramento) believe her uncertainty is over? Well, Frances’s parents are played by Gerwig’s real mother and father, and I don’t think I’d have the heart to ask them.

For the moment, Gerwig is floating, like a girl of her own dreams. She and Baumbach were effectively married in ten pages of rapture in The New Yorker in April. It’s all cool and sudden. She had been to Barnard, acted a bit, and got caught up in the mumblecore movement, a scheme for (or a defense of) cheap, naturalistic, and eventless movies with amateur actors seeming improvised even if the script was typed out many times. (It was a method that owed something to Baumbach’s film Kicking and Screaming, from 1995.) Gerwig made some films in that mood, playing a version of herself and often helping on the scripts. You may know her from a role in Woody Allen’s To Rome with Love, or you may be trying to forget that. In 2010, she had been a lead actress in a film called Greenberg, directed by Baumbach and co-written by him and Jennifer Jason Leigh, who also played a role in the movie and was married to him.

That’s an interesting story. Baumbach, who is now forty-three, is the son of Jonathan Baumbach (a teacher, novelist, and writer on film) and Georgia Brown, who was an unusually personal film critic at The Village Voice. In the last ten years or so, he has become very active: he directed Mr. Jealousy, The Squid and the Whale, and Margot at the Wedding, as well as Greenberg, and he has writing credits on The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and Fantastic Mr. Fox. The Squid and the Whale seemed to me one of the best new films of the early century, and I liked Margot at the Wedding, in which Leigh and Nicole Kidman played competing sisters with humor and insight. Leigh, who is now fifty-one, had a child in March 2010, named Rohmer (yes, after Éric), and then a few months later she sued for divorce. I don’t know any more about the facts, except for one thing. Over the decades I have learned to recognize a kind of film in which the director is doing the picture to be close to the actress because he loves her; and in such an undertaking, sheer time-consuming photography and presence can take over from narrative or character.

That is not as bad as it sounds. Plenty of young men have gone into film to meet women, and making and watching films is a large (and perilous) stimulus to desire. You could make a season of films like that, and it would have to include Griffith and Lillian Gish (Broken Blossoms); von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich (Morocco, The Devil is a Woman); Antonioni and Monica Vitti (L’Avventura); Hawks and Lauren Bacall (To Have and Have Not); Capra and Barbara Stanwyck (The Miracle Woman, The Bitter Tea of General Yen); Godard and Anna Karina (Vivre Sa Vie, Pierrot le Fou); Ingmar Bergman and nearly every actress he worked with (Persona, Cries and Whispers, Summer with Monika); Hitchcock and Grace Kelly (Rear Window), and Hitchcock and Tippi Hedren (The Birds, Marnie); and Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau (Jules and

Jim) and Truffaut and Catherine Deneuve (Mississippi Mermaid). You might add Leni Riefenstahl and Triumph of the Will, an immense surge of passion for a man.

Frances Ha is not at that level, but it feels like the work of a talented but insecure director who has grown up on the legend of those films. There are times when that approach runs the risk of stranding a willing young woman and leaving the audience to agonize over what is happening while the director gazes at the actress. It is an equation that makes some great movies, and others that would be better handled in private or without bothering to put film in the camera.

I don’t know what happened in this triangle, but it seems richer material for a movie than Frances Ha. I would add that, while there have been indications that Jennifer Jason Leigh can be introverted, shy, and maybe even difficult (I am guessing), she is a great actress. She was in Fast Times at Ridgemont High before Greta Gerwig was born, and a short list of her brilliance would have to include Last Exit to Brooklyn, Rush, Single White Female, Short Cuts, Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, Georgia (her singing of “Take Me Back” in that film is better than many careers), In the Cut, and several others. Consider just Georgia: it is not a perfect film, but the relationship between sisters (Mare Winningham is the other one) has a pain, depth, and affection, a truth, that makes the ties between Frances and her best friend, Sophie (Mickey Sumner), feel touching but cursory. Leigh has never been nominated for an Oscar, but she has twice won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for acting and has been nominated twice more.

In 2001, moreover, she co-wrote, co-produced, and co-directed (all with the mercurial Alan Cumming) a little get-together movie called The Anniversary Party, Altmanesque if you like, but beguiling and very moving. A lot of critics expressed a hope that Cumming and Leigh would work together again. (They both played leading parts in the film.) That hasn’t happened yet, but The Anniversary Party is so much more absorbing than Frances Ha.

The comparison to “Girls” is inescapable: Adam Driver is in both that series and this film, and the emotional territory and the urban locale are so close. It’s not just that Lena Dunham is braver than Frances Ha. It’s more that, while “Girls” was made for an audience who resembles its characters, Frances Ha has a cozy parental appeal. This is for those of us who worry about our kids out of college in the city. Baumbach and Gerwig settle for the palatable conclusion that it’s all going to be all right. There aren’t any unpleasant people in Frances Ha. No one comes to a bad end or really suffers in ways that would devastate parents, instead of urging them to send more money. Sex is talked about in Frances Ha, but in “Girls” (as you may have heard) it happens, and it is part of Dunham’s artistic cool that she knows other girls beyond models want to have sex, and are ready to be humiliated in the hunt.

“Girls” takes great risks and sometimes falls on its face (which can be a painful experience). The risks in Frances Ha are cute and playful, and in time it may look not just like a fifty-year-old New York New Wave picture, but also as embarrassing as those photographs you burn before you get married. Noah Baumbach has a lot of talent, and great appetite for pure cinema, but I don’t think he is the screenwriter he deserves.

David Thomson is a film critic for The New Republic.