Proprioception refers to the body’s sense of itself in space; or, more specifically, to a sense of its parts in relation to one another. In Anatomies, British writer Hugh Aldersey-Williams attempts something comparable to this bodily orientation on a social scale, a kind of cultural proprioception that maps our endless exploration of our own physical selves. Along the way, he shows us some extraordinary things: a shrunken head full of hot stones, a dress made of eyes, a wall made of vulvas. He starts at the dissection table and ends at a life-drawing class.

The book’s subtitle (“A Cultural History of the Human Body”) suggests its staggering breadth of purpose: It’s not so much an attempt to make sense of the body as an attempt to make sense of all the ways we’ve ever tried to make sense of it. We’ve sought causality and possibility. We’ve made maps. We’ve hunted cures. We’ve found homes for abstractions (thought, feeling, heredity) in discrete bodily locations (brain, heart, blood). “The body,” as pairing of noun and definite article, has achieved a certain aural familiarity—a generalized figuration of our own separate forms. We talk about demands of the body, failures of the body, pleasures of the body. “The body” turns embodiment into something abstract—grounds for metaphor or figuration—rather than a set of particular moments contained in particular flesh: this body.

If the abstraction of “the body” turns flesh into notion, then Aldersey-Williams’s vision is nearly opposite: he wants to keep bodies alive. He wants to liberate them from the long shadow of dualism—a conception of the body as a corrupt vessel of the spirit. He wants to correct Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher who told his students: “You are a little soul carrying around a corpse.” Anatomies seeks something closer to the “kinetic beauty” David Foster Wallace once found in Roger Federer’s tennis, which has to do with “human beings’ reconciliation with the fact of having a body.” Aldersey-Williams attempts his own reconciliation here. “There is no escape,” he writes, “but that does not mean we should regard as a prison what is in fact our home.”

His task is difficult, for all the obvious reasons. He is cramming a “cultural history” of everything we are into 270 pages—trying to gaze at our collective navel from a thousand angles at once. Sections like “Skin” or “Hands” offer a buffer against the vastness of his subject, discrete frames in which he can arrange—or rather, leave somewhat unarranged—a wide array of materials: a collage of citations, examples, and anecdotes from history, science, myth, anthropology, literature, and art. The grab bag is—by turns—electric and unwieldy.

The main trouble is that Aldersey-Williams doesn’t approach his collage in a particularly rigorous way. Instead, he offers something closer to a massive cocktail-party primer filled with anecdotal pearls (martyrs buried away from their own hearts); cultures-say-the-darndest-things-style idioms (the Germans call a bad mood a “louse running over the liver”); and a cast of quirky figures: the Russian poet who bound a book of sonnets to his mistress with the skin of his own amputated leg, the doctor who preserved the body of a beautiful prostitute in whiskey, the geologist who decided to taste every kind of animal (he managed puppy, panther, garden snail), the lovers who got rings made from each other’s bone tissue. I found myself strangely moved by the tale of Dr. Thomas Harvey, who cut Einstein’s brain into hundreds of pieces—without anyone’s permission—in order to distribute them to pathologists so they could figure why he’d been so smart.

It shouldn’t come as much surprise that Aldersey-Williams has worked extensively as a curator.1 What he’s accomplished in this book is a feat of gathering more than argument or interpretation. But I wanted him to reckon more courageously with the ideas emerging from his curiosity cabinet: the tension between looking at the body in pieces or as a whole; the parallels between anatomical and geographical discovery, body parts named for anatomists the way peninsulas were named for explorers; the constant quest to find metaphors to explain the body, or to turn the body into metaphors that could explain everything else. We get the embryonic structures of all these fascinating notions—including, for example, what it might mean that we use bodily metaphors (e.g., “embryonic”) so frequently—but no guiding argument linking them together. Aldersey-Williams is often content to let broad ideas taper into trailing questions that don’t provoke so much as show us how little they’ve been answered. A driving argument carries the risk of a certain conceptual violence—the possibility that every observation would be bent to fit the strictures of its thesis—but it also offers an organizing principle. Argument turns accumulation into something more than a sum of parts. It offers the traction of possible disagreement. Argument is risk. This book is safe.

Perhaps my own frustration at the mode of Anatomies—the way it opened roads of inquiry without following them—simply expresses a sense of imperative: I feel I owe the human body some degree of serious effort. Perhaps a Puritan work ethos has attached itself to a Puritan bodily shame: I want to work hard thinking about the body in order to make it okay that I have one. The ease of Aldersey-Williams’ approach feels somehow indulgent, reminiscent of the quickie pleasures of a tourist: snapping photo-ops of all the good stuff and jetting off before the history lesson. We collect the souvenirs of factoid and anecdote—earrings were worn to ward off demons from the ear canal!—but there’s no work of reckoning. It’s particularly strange to feel like a tourist when the territory in question is your own body—your own and everyone’s.

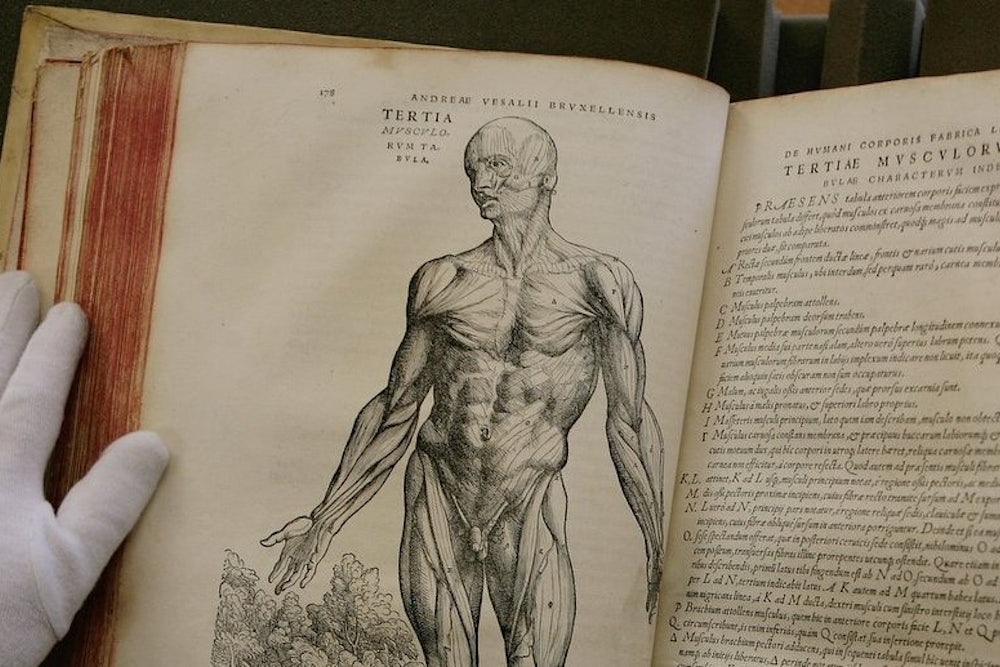

To be fair, this abiding irony is one of the central preoccupations of Anatomies: Aldersey-Williams acknowledges that even though there is nothing closer to us than our bodies, we can’t ever look at them fully. Every glance at where we live—at what we live inside of—is necessarily, inescapably incomplete, and this sense of epistemological futility has produced a legacy of exploratory violence. We keep breaking ourselves open in order to get a better look. This violence isn’t simply the violation intrinsic to dissection but also its prerequisite procurements: claiming the bodies of criminals, exhuming buried men, murdering for profit.2 Aldersey-Williams describes the grotesque bodies that populate the illustrations of De Humani Corporis Fabrica,a 1543 anatomical encyclopedia: bodies mutilated by the process of exposure, skin peeled away from muscles in ragged strips, forms contorted to show possible pieces and postures, even—in one engraving—the strange suggestion of violent self-exposure: “a muscled body stands knife in hand, triumphantly holding aloft his own excoriated skin.” These illuminations hold horror, but also a sense of dark wonder, a reminder that knowledge is always full of damage.3 Dissection means you sever connections to see how they work. Vivisection means you hold a beating animal heart in your hand; you feel how it contracts into a stone, then sends the blood flying.4

As Aldersey-Williams points out: “I cannot ‘part,’ which is to say separate, any one part from the rest of my body without drawing blood.” Which is to say: Examination requires removal, breaking the surface, damaging disentanglement. Bodily knowledge necessarily comes tainted with the knowledge of mortality: Aldersey-Williams reminds us that when Thomas Mann’s protagonist Hans Castorp sees his arm in an X-ray in The Magic Mountain, he also sees what “no man was ever intended to see … he saw his own grave.” Seeing our bodies also means seeing how or why or simply that we are going to die. If death itself isn’t always legible, then breakage often is: Aldersey-Williams describes an art project in which a ballerina dances until she faints, an aesthetic incarnation of one of the oldest kinds of spectacle—in which human exhaustion or peril or dismemberment is turned into entertainment. People paid to watch other people dance themselves to the point of collapse during the Great Depression. People paid to watch slaves fight lions in the Roman coliseum. People paid to see Dr. Tulp’s anatomy lesson in Amsterdam in 1632. These spectacles aren’t equivalent, but they rhyme. They all point toward the moment of visibility that occurs when the body falters or breaks, or gets broken, or gets cut.

There is something poignant about all this cutting and hacking and robbing and bending and breaking, this bloodletting of mystery, something powerful about chopping Einstein’s brain to pieces in order to figure out what makes us extraordinary. We’re knocking on the big brute door of the body and hoping a spirit answers. We want the physical to hold the metaphysical in legible form. We want to break open the skull of a genius and find something waiting inside that could—after all this slice and rupture—finally explain us to ourselves.

He helped design an entire exhibit on touch—that bastard cousin of the higher senses—and put together an exhibit on “animal architecture” for the Victoria & Albert Museum, pairing taxidermy animals with architectural models: a skyscraper shaped like a sea sponge, a country manor inspired by the starfish.

Critic Ruth Richardson calls Henry Gray’s legion of anonymous dissected bodies the “silence at the centre of Gray’s [Anatomy].”

“Split the lark,” Emily Dickinson writes, “and you’ll find the music … gush after gush, reserved for you.” She describes breaking open a bird to examine the magic of its song, prove its “veracity”—a “Scarlet experiment” that destroys the wonder it wanted to excavate. The observer effect is figured as a kind of scalpel wound; music unravels as spilled blood.

It calls to mind the raw anatomy lessons of “Closer,” the zeitgeist-sculpting Nine Inch Nails video where Trent Reznor sings “You let me violate you” while the materials of his steampunk dissection lab—ghoulish skeleton, chained monkey, exhaust valve heart—quiver and struggle and beat behind him. He’s talking about sex, of course—the other way to get inside a body—but his crude materials suggest a desire for knowledge as well as pleasure, a desire to get closer to mechanisms as well as flesh. The desire feels desperate. It bleeds.