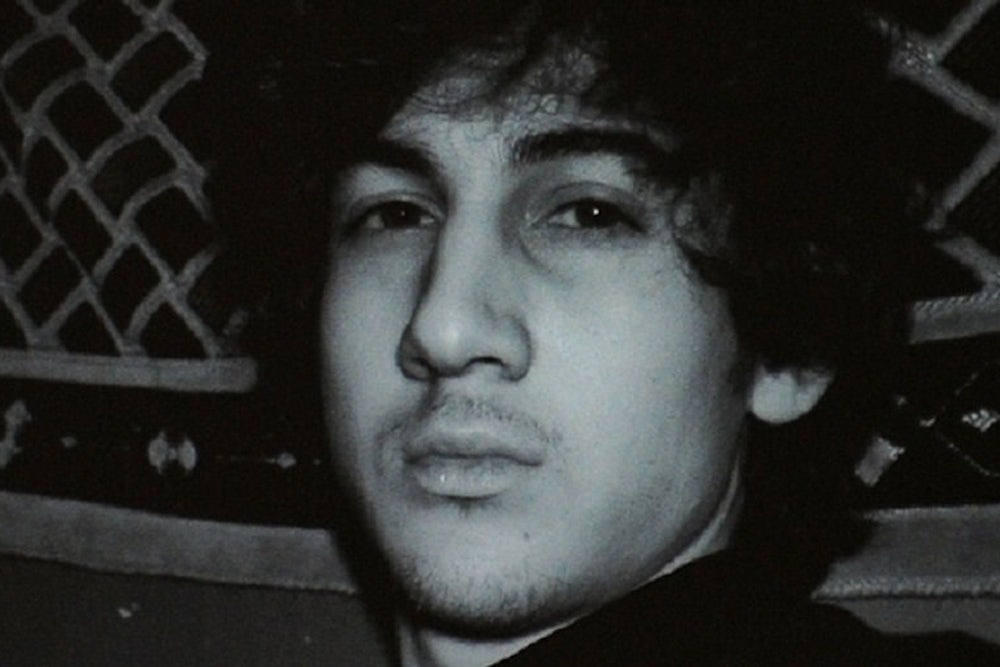

“A decade in America already, I want out.” This tweet of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s has helped fuel speculations that what drove him to mass murder was that America had failed to assimilate him thoroughly enough.

In fact, whatever investigations of his psychology reveal, his tweets and texts alone confirm that he was quite the assimilated young man. This is clear not only in the typically teen male subject matter, as many have observed, but in the form of language he was so casually using—namely, the well-established but subtle new grammatical constructions of modern texting and tweeting and also, of all things, Black English.

Anyone brought to 2013 to examine Dzhokhar’s tweets, for example, would be shocked to find out that he isn’t black. His tweets are full of not only quotations from rap music—this exemplifying the “teen normal” essence of the guy—but spontaneous locutions which, before his generation, were all but unknown beyond black people.

“Yeah man we good mashallah,” Dzokhar tweeted on April 15th, when a friend innocently looked him up after the bombing. Many will look first to the implications of his use of the Arabic “good luck” term as possible evidence of his turn to violence. However, just as indicative of where his head was is the “we good”—this deletion of the be verb is a hallmark of Black English. Likewise, a post-attack tweet that read “Ain’t no love in the heart of the city, stay safe y’all” has attracted attention for quoting a Jay-Z lyric, but the “stay safe, y’all” is Dzhokhar alone. Certainly, y’all is well known among whites as well as blacks, but there are nuances. Imagine a white kid in 1978, outside of the South, winning a call-in radio contest and giving a salutary shout-out to listeners “Stay safe, y’all!” Notice it just doesn’t translate even if the kid is from working class Brooklyn or Providence. “Stay safe ya’ll,” in most of the US, is blackspeak.

Or it used to be. Over the past twenty years Black English has become a kind of youth lingua franca in America. During the controversy over the Oakland School Board’s proposal to use “Ebonics” in classrooms in 1996, it was a novel observation that Latino, Asian and even white kids were no longer strangers to the dialect. Scholars were just beginning to analyze the white ones, known as “wiggers,” as fascinating examples of reverse crossover.

Today, “wigger” is a virtually useless term. In terms of not only speech but musical taste and even gestures—these days not only white girls but Asian girls, and all other kinds of American girls, casually do the neck-twist when stressing a point, a tendency that not so long ago was known only among black women—there is a bit of “wigger” in any young American these days.

One way we know that Dzhokhar was thoroughly American at heart is that he had soaked this up along with everything else. Language is a vivid index of identity, what one feels at one with. With tweets like “I don’t care for those people who wanna commit suicide, your life b, do what you think will make you happy”—the Urban Dictionary’s first definition of that “b” is “a greeting to one of your homies”—he indicated a perfectly ordinary Americanness.

A useful contrast would be Seung-Hui Cho, the young man who killed 32 at Virginia Tech in 2007 before killing himself. Cho had come to America from Korea at 8, an age at which people still regularly acquire the language of a new place flawlessly (as Dzhokhar, arriving here at 9, had). Yet there were reports that he spoke strangely, and oddly little. Here was someone who, in this and general social remove, was quite obviously unassimilated to the society around him. The contrast in Dzhokhar is clear.

As is the irony—that the speech patterns of black people, historically so deeply despised by mainstream America, are now what identifies the true Americanness of a humble immigrant kid from an obscure region of the Caucasus Mountains. One ongoing thread of modern black American consciousness worries about the costs of assimilation, in a fear that white Americanness will erase cultural blackness. Yet too often we miss the brownification of mainstream American culture that has occurred over the past fifteen years, such that forms of English most of us associate with hiphop and "The Wire" are heartfelt, spontaneous expression for someone named Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

Dzhokhar was also quite fluent in another language of sorts, the conventions that have jelled for texting and tweeting among people exactly his age over the past ten years. “How I miss my homeland #dagestan #chechnya” strikes us now for evidence of disidentification from America, but his attitudinally fluent recruitment of the hashtags indicates just as much. Before Dzhokhar lived in America, no one was tweeting at all, much less using hashtag in irony—he learned that witty reinterpretation of the symbol in America. It is highly unlikely that he intended those hashtags as actual encyclopedic pointers to Twitter discussions of the two regions. Rather, he was using the hashtags in their newish Twitter signification as setting topic off in irony.

This is even clearer in a tweet that reads, “I killed Abe Lincoln during my two hour nap #intensedream.” The intent is not to refer us to a thread about dreams, but to suggest his experience as viewed from a distance, treated as a genre piece rather than a personal experience. Teen self-consciousness and drama? Sure – but in exactly the language that teens are currently using right here in America.

Then, of course, there was the ominous LOL that he used to answer a friend’s query before his capture. It has become a media meme of late that LOL no longer means “laugh out loud.” Rather, it is a multifarious marker of assorted sentiments that cluster around a core of empathy. LOL, which often decorates teen and twenty-something texts as thickly as “like” decorates their speech, means not “I’m laughing” but “I feel you.”

No one thinks about that consciously; they just do it, the way we use language almost all of the time. Dzhokhar had internalized the subtlety of LOL just like millions of American kids have over the past several years.

In short, despite his native Russian, nothing in Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s linguistic repertoire—laced with black English and spirited usage of the brand-new particularities of smartphone language—suggested anything but, a young person as American as hot dogs, apple pie, Chevrolet, and, well, rap. The unwelcome thing is that this means that identifying what tipped him into nihilistic savagery will be that much more difficult.