Pity the poor soul who one day decides to write a biography of Janet Malcolm. She has little patience for “the arrogant desire to impose a narrative on the stray bits and pieces of a life that wash up on the shores of biographical research.” But oh, what tantalizing bits are on offer!

Malcolm’s life began privately enough. After her family emigrated from Prague in 1939, she headed from her family home in New York City to the University of Michigan; to Washington, D.C., where she wrote book reviews for this very publication; and then headed back to New York with her first husband, where her work—shopping pieces and interior decorating columns—began to appear in the New Yorker throughout the 1960s and ’70s.

It was at that magazine that Malcolm came into her own as one of the premier nonfiction narrative writers of her time. Leaning heavily on the techniques of psychoanalysis, she probes not only actions and reactions but motivations and intent; she pursues literary analysis like a crime drama and courtroom battles like novels. Readers appreciated her dry wit and willingness to share the behind-the-scenes action of reporting. The “journalistic I”—usually used as an “overreliable narrator,” she wrote—is actually a person with her own foibles and prejudices. She even cops to the boredom of reporting. “The truth,” she wrote in her 1999 book The Crime of Sheila McGough, “does not make a good story; that’s why we have art.”

Ah, but sometimes, truth gives art a run for its money. In 1990, Malcolm published The Journalist and the Murderer, a book that examined a lawsuit brought by a convicted killer (Jeffrey MacDonald) against a writer (Joe McGinniss) who ostensibly betrayed him. McGinniss had promised to write a sympathetic book about MacDonald’s trial, but when the book came out it was anything but sympathetic, leading the murderer to sue the journalist for libel. Malcolm’s book about the MacDonald and McGinnis began with the now infamous line: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.” Through the relationship between these two men, Malcolm probed the relationship between any subject and journalist; the latter was “a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance or loneliness.” Unsurprisingly, many in the press viewed this as a gauntlet; what followed, as Albert Scardino wrote in the New York Times, was “a storm of criticism about Malcolm’s own behavior.”

Had Malcolm’s critiques existed purely in the realm of the abstract, it’s doubtful she would have become a lightning rod for the public debate over journalism’s dawning crisis of conscience. But she was herself involved in a not-dissimilar suit: Six years before The Journalist and the Murderer was published, psychoanalyst Jeffrey Masson, the subject of Malcolm’s previous book, In the Freud Archives, claimed that she had fabricated quotes and sued her for libel. Many observers saw The Journalist as a barely sublimated meditation on her own ongoing legal trouble—something that was neither truth nor art, but more like solipsism.

Perhaps it is her elliptical style, which encourages readers to infer much on their own, that led people to this conclusion. Perhaps it is her frequent references to psychoanalysis and her willingness to explore the quiet inner deliberations of her subjects. Or perhaps it is Malcolm’s own reticence early on in her career to speak with the press: deeper meanings were sucked from her books to fill the vacuum of her silence. Whatever the reason, critics arose to attack her for The Journalist. The plaintiff in the case against Malcolm, Masson, said, “She’s really writing about herself. [The Journalist] sounds like a confession—a personal letter confessing something she feels terrible about.” (This quote appeared in a New York magazine article unambiguously titled “Holier Than Thou.”) Five years later, writing about her 1995 study of Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, The Silent Woman, Caryn James reported in The New York Times, “The word was that ‘The Silent Woman’ was all about Janet Malcolm.” Although Malcolm herself was at pains to disabuse critics of these notions, it is hard—as Malcolm has spent much of her career arguing—to change the consensus of an aligned press.

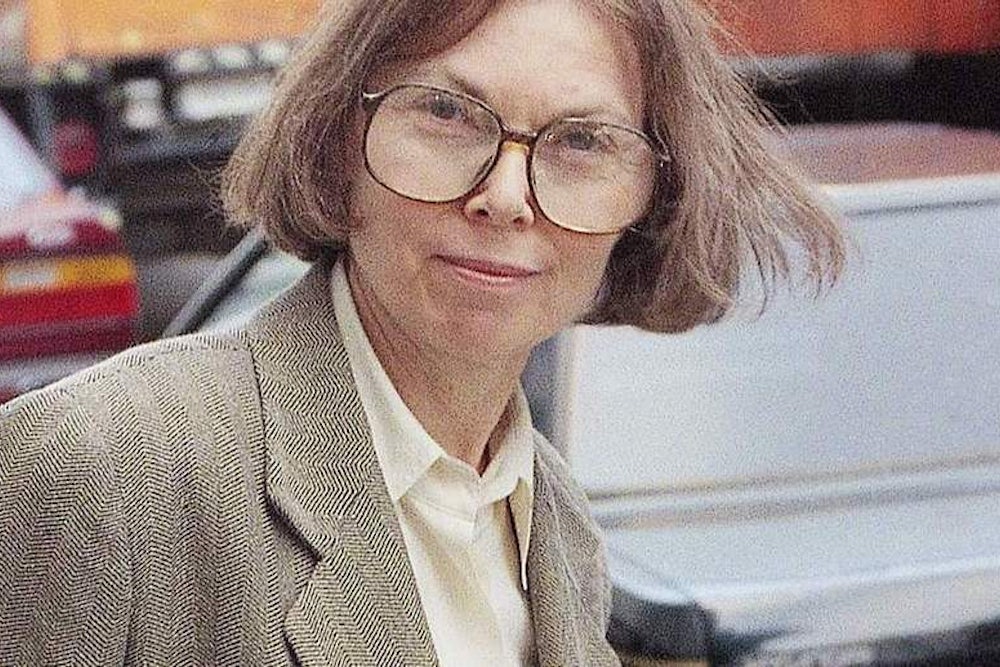

AP Photo/George NikitinJOURNALISTIC TRIALSThe New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm leaves courthouse in San Francisco in 1993.

If Malcolm was dismayed by these accusations, she should not have been surprised by the tooth and claw of other journalists. “The narratives of journalism,” she writes in The Silent Woman, “derive their power from their firm, undeviating sympathies and antipathies.” Malcolm was now firmly cast in the role of journalism’s internal provocateur; while her libel suit dragged on, few defended her as might have been expected, and occasional digs against her continued to appear in the magazines that care about such things (a 2011 piece in Esquire called her “full of shit,” “self-serving,” and “self-descriptive”). But, much to her credit, she has hardly wilted in the face of these overblown attacks. It’s been said that Malcolm herself “discovered her vocation in not-niceness.” Her new collection—her first in ten years—Forty-One False Starts reminds just how fun her not-niceness can be.

Considering the intensely intellectual style for which she is known (Katie Roiphe described it in a 2011 Paris Review interview as an “admixture of reporting, biography, literary criticism, psychoanalysis, and the nineteenth-century novel”), it’s easy to forget what a pleasure Malcolm is to read. Here, wit and impossibly high-minded zingers fly as she wanders through the lives (and egos) of artists, past and present. Under her gaze, Julian Schnabel has “the modestly pleased air of a successful entrepreneur.” German photographer Thomas Struth, caught referencing Proust without having read him, grimaces, realizing that his “picture was already on the way to the darkroom of journalistic opportunism.” From the profile on fading art star David Salle to a review of the Gossip Girl novels (“strange, complicated books,” far from the “sluggish and crass” television adaption), these essays serve as a reminder of how much Malcolm has influenced young reporters’ willingness to challenge the profession’s conventions. The essays in this book rail against thoughtless assumptions about writing and the arts with clean prose, an uncanny eye for the unexpected detail, and a willingness to implicate herself in a story in order to retain her ability to surprise readers.

As a critic, Malcolm owns her biases, and allows the reader to join her as she interrogates what these predilections reveal about gender, race, class, and the other thorny issues. She illuminates some orthodoxies and overturns others (sifting through J.D. Salinger’s then-reviled Franny and Zooey, contemplating Edith Wharton’s misogyny). And then there’s the question of niceness, which often lingers at the periphery of her work: the excessive niceness photographer Diane Arbus applies to her subject or the non-niceness of the formidable art critic Rosalind Krauss, who “makes one’s own ‘niceness’ seem somehow dreary and anachronistic.” Malcolm has her own form of non-niceness, and it is on full display in this collection in “A Girl of the Zeitgeist,” which ostensibly chronicles a changing of the guard at Artforum magazine but is really a skewering of many of the major players in New York’s mid-1980s art scene.

Ultimately, it is the sharpness and creativity of this writing that sticks. Malcolm built her reputation by breaking the strict rules of civility and journalistic lockstep, but those rules today seem rather quaint. It’s easy to imagine, for example, David Foster Wallace ruminating over a lobster as a direct descendent of her deconstructionist-inflected work. Recent years have seen her shedding the narrative of embattled gadfly. As Malcolm herself said of the now-canonical Journalist and the Murderer in her interview with Roiphe, “Today, my critique seems obvious, even banal.”

But if her work no longer spurs hand-wringing among the literati, it remains well-worth talking about. It is apt that this collection focuses on artists and writers; Malcolm’s preoccupation with how we tell stories and why we tell them the way we do is a fitting meta-theme for these investigations in the creative act. Joan Didion’s assertion that we tell ourselves stories in order to live is a poetic one, but in a media-saturated world such as ours, Malcolm’s art is to point out that it’s a little more complicated than that.

This article has been corrected. A caption originally stated that a jury found that Jeffrey Masson had been misquoted and libeled in a 1993 trial. In fact, that trial resulted in a mistrial.