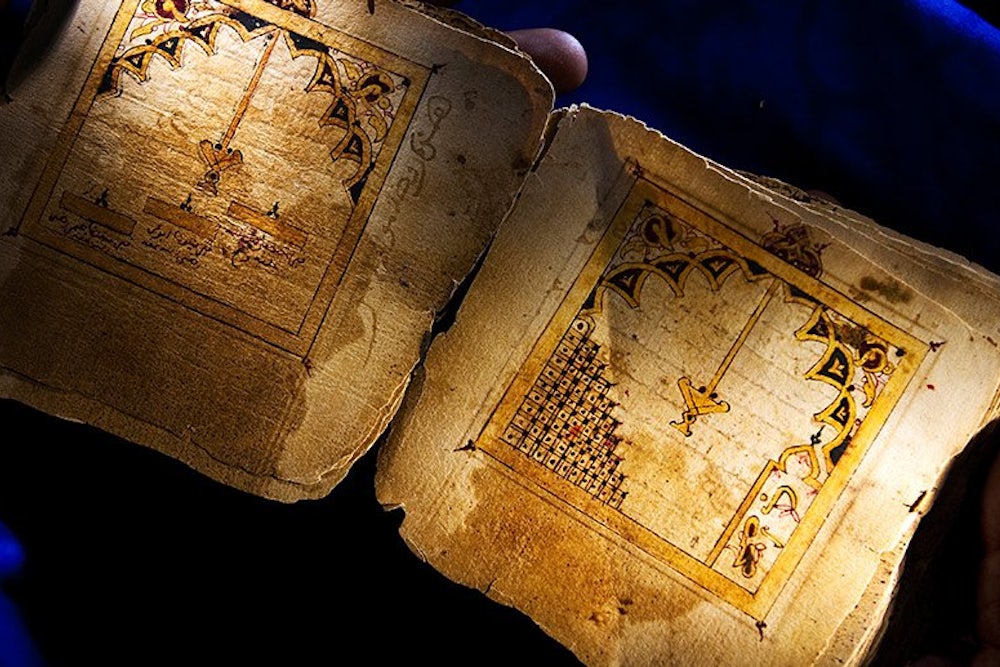

One afternoon in March, I walked through Timbuktu’s Ahmed Baba Institute of Higher Studies and Islamic Research, stepping around shards of broken glass. Until last year, the modern concrete building with its Moorish-inspired screens and light-filled courtyard was a haven for scholars drawn by the city’s unparalleled collection of medieval manuscripts. Timbuktu was once the center of a vibrant trans-Saharan network, where traders swapped not only slaves, salt, gold, and silk, but also manuscripts—scientific, artistic, and religious masterworks written in striking calligraphy on crinkly linen-based paper. Passed down through generations of Timbuktu’s ancient families, they offer a tantalizing history of a moderate Islam, in which scholars argued for women’s rights and welcomed Christians and Jews. Ahmed Baba owned a number of Korans and prayer books decorated with intricate blue and gold-leaf geometric designs, but its collections also included secular works of astronomy, medicine, and poetry.

This vision of a philosophical, scientific Islam means little to the Al Qaeda–linked Islamist group Ansar Dine, which for most of last year ruled Timbuktu through terror, cutting off the hands of thieves, flogging women judged to be dressed immodestly, and destroying centuries-old tombs of local saints. In the summer, the militants commandeered Ahmed Baba, using it as a headquarters and barracks. Then, in January, French forces closed in on Timbuktu. As the Islamists fled, they trashed the library, burning as many of the manuscripts as they could find. The mayor of Timbuktu, Hallé Ousmani Cissé, told The Guardian that all of Ahmed Baba’s texts had been lost. “It’s true,” he said. “They have burned the manuscripts.”

When I visited Ahmed Baba two months later, the rows of wooden bookcases in the large, sunlit rooms were empty. The only traces of the ancient documents were a pile of mottled gray-and-black ashes, a few empty leather cases, and a single book-sized manuscript lying loose on the floor. I picked it up: The spidery Arabic on its cover was mostly obscured by singe marks, the pages inside reduced to dust.

Asking around about the manuscripts’ destruction, however, I heard different rumors. Find Abdel Kader Haidara, people told me. He could tell you more about what happened. So, in Bamako, Mali’s capital 400 miles to the south, I visited Haidara, an unassuming man with a shy smile, a neatly groomed mustache, and a healthy paunch under the flowing robes traditional to Malian men. Sitting cross-legged on the floor of the modest apartment where he now lives, Haidara told me the improbable story of what actually happened to Timbuktu’s manuscripts. “It was only a matter of time before the Islamists found them,” he said matter-of-factly, passing dark worry beads between his fingers. “I had to get them out.”

When Abdel Kader Haidara was 17 years old, he took a vow. Among the families of Timbuktu with manuscript collections (and the Haidaras had one of the largest), it’s traditional for one family member from each generation to swear publicly that he will protect the library for as long as he lives. The families revere their manuscripts, even honoring them once a year through a holiday called Maouloud, on which imams and family elders perform a reading from the ancient prayer books to mark the birth of the Prophet Mohammed. “Those manuscripts were my father’s life,” Haidara told me. “They became my life as well.”

That life came under serious threat last year, when a military coup ousted Mali’s democratically elected leader just as a loose alliance of Tuareg separatists and three Islamist militias began conquering broad swaths of the north. The rebels quickly routed the Malian army, and Timbuktu fell in April 2012.

As the militias poured into his city, Haidara knew he had to do something to protect the approximately 300,000 manuscripts in different libraries and homes in and around Timbuktu. Haidara had spent years traveling around the country negotiating with Mali’s ancient families to assemble thousands of texts for the Ahmed Baba Institute, which was founded in 1973 as the city’s first official preservation organization. “When I thought of something happening to the manuscripts, I couldn’t sleep,” he told me later.

The initial wave of invaders were secular Tuareg, but quickly the Islamist militia Ansar Dine asserted control, imposing a harsh regime of sharia in Timbuktu and other northern cities. The Islamists didn’t know, at first, about the manuscripts. But their indiscriminate cruelty and their tight-fisted control over the city meant that the texts had to be hidden—and fast. Haidara thought the manuscripts would be most secure in the homes of Timbuktu’s old families, where, after all, they had been protected for centuries. He assembled a small army of custodians, archivists, tour guides, secretaries, and other library employees, as well as his own brothers and cousins and other men from the manuscript-holding families, and began organizing an evacuation plan.

Starting in early May, every morning before sunrise, while the militants were still asleep, Haidara and his men would walk to the city’s libraries and lock themselves inside. Until the heat cleared the streets in the afternoon, the men would find their way through the darkened buildings and wrap the fragile manuscripts in soft cloths. They would then pack them into metal lockers roughly the size of large suitcases, as many as 300 in each. At night, they’d sneak back to the libraries, traveling by foot to avoid checkpoints on the road, pick up the lockers, and carry them, swathed in blankets, to the homes of dozens of the city’s old families. The entire operation took nearly two months, but by July, they had stowed 1,700 lockers in basements and hideaways around the city. And they did it just in time, because not long after, the militants moved into the Ahmed Baba Institute, using its elegant rooms to store canned vegetables and bags of white rice. Haidara fled to Bamako, hoping the Islamists’ ignorance about the texts would keep them safe.

Over the summer, the Islamists became brasher and more destructive. They began a campaign of assault on the city’s most cherished religious sites, its mausoleums of Sufi saints. In July, the militants knocked down the doors of the fifteenth-century Sidi Yahia Mosque, doors that were meant to stay closed until the last day of the world. Then, in September, Haidara began to receive panicked calls from Timbuktu. The Islamists were breaking into private homes, particularly those of the city’s oldest families, and stealing anything that they could sell on the black market. For the moment, they were focused on flat-screen televisions, stereos, and computers, but Haidara knew eventually they would begin searching the houses more carefully. It was time for the manuscripts to leave Timbuktu altogether.

Stephanie Diakité is an unlikely ally for Timbuktu’s manuscripts. She grew up in Seattle, a deeply intelligent and highly educated woman with short blond hair and a habit of ending her sentences on a lilting “huh?” On a trip to Timbuktu 20 years ago, she met Haidara and his documents and found a calling: The texts, she says, “do something for me nothing else ever has.” Diakité apprenticed with master bookbinders and has spent her life shuttling back and forth between the United States and Africa, working on conservation projects. When Haidara realized he had to spirit the documents out of Timbuktu, Diakité was the first person he contacted. The two friends spent days in Bamako cafés, sipping tea and devising plans.

Haidara started by recruiting couriers back in Timbuktu, phoning up dozens of young people he knew through the libraries there. Diakité organized a financial structure to funnel money through Bamako businessmen to the couriers in Timbuktu for their salaries, car and truck rental fees, and the inevitable bribes that would need to be paid along the way. On October 18, the first team of couriers loaded 35 lockers onto pushcarts and donkey-drawn carriages, and moved them to a depot on the outskirts of Timbuktu where couriers bought space on buses and trucks making the long drive south to Bamako. That trip was replicated daily, sometimes multiple times a day for the next several months, with many teams of smugglers passing hundreds of lockers along the same well-worn pathway.

The couriers faced a slew of dangers, not least Ansar Dine, which controlled half of the territory between Timbuktu and Bamako. The Malian countryside is anarchic at the best of times, and during the Islamic occupation, bands of masked criminals roamed loose, kidnapping people for ransom, demanding bribes, and robbing the vehicles fleeing south. Malian government forces were, just as often, corrupt, incompetent, or so jittery as to be worse than useless. Soldiers and police regularly pulled guns on couriers or searched their cars. A team of couriers was detained a few weeks after the smuggling began and Haidara, who mostly kept out of day-to-day operations, had to negotiate their release personally. Other couriers were stopped and questioned at Islamist checkpoints, although no one was ever badly hurt.

As the rescue effort continued into the winter, ordinary Malians began joining in. When housewives along the way saw at checkpoints what the couriers were carrying, they provided food and shelter, while local villagers tried to distract soldiers so the smugglers could pass unnoticed. Truck drivers would offer rides to couriers toting heavy lockers on their backs or guiding donkey carts.

In January, French troops began aerial and ground attacks in the north, making it too dangerous for couriers to use the roads. Instead, they loaded the lockers onto small motorized skiffs called “pirogues” and ferried them down the Niger River to the ancient market town of Djenné, where they were handed into cabs and driven to Bamako. But although the French were notified of Haidara and Diakité’s evacuation, the message didn’t filter down to the ground level. Around January 15, an armed French helicopter swooped over a pirogue and demanded that the couriers open their boxes—or be sunk on suspicion of harboring weapons. The helicopter flew off, Diakité told me, once the French pilots saw the ship was carrying nothing but old piles of paper.

The French invasion was a relief to Diakité and Haidara in Bamako, but in Timbuktu, the situation began to take a terrifying turn. Having destroyed half of the city’s major shrines, Ansar Dine was looking for new targets for destruction—and the nearing date of Maouloud, the holiday celebrating the Prophet’s birth through the reading of the manuscripts, seemed to give them an idea. In mid-January, the leaders of Ansar Dine summoned the city’s imams and the heads of its oldest families and made an announcement: Maouloud was now haram, forbidden. Worse, the city’s elders had to turn over all the manuscripts so they could be burned before the holiday began in late January. At this point, 700 lockers were still in the city. Haidara and Diakité knew they would have to get all of them out immediately, with no time to spare.

Frantically, they started calling all the couriers in Timbuktu, ordering them to load the lockers onto boats as quickly as possible. And their couriers came through—within days, the hastily assembled troupe had managed to pull together all the remaining lockers and load them onto 47 boats, traveling down the Niger. A few days later, near Lake Débo, about 300 miles northeast of Bamako, 20 of the boats entered a narrow strait of water. Suddenly, groups of men, their heads covered with turbans, materialized on both sides of the river, waving automatic weapons and ordering the boats to stop. The couriers had no choice but to pull their pirogues up to the shore, where the gunmen said they would burn their cargo unless they could deliver an astronomical sum of money. The teenage couriers pooled their cash, watches, and jewelry, but it wasn’t enough.

Finally, the gunmen allowed the couriers to call Haidara on his cell phone, and Haidara—sitting with Diakité in her Bamako office—began negotiating the ransom of his beloved manuscripts. “He basically gave them an IOU,” Diakité told me. “It was like Abdel Kader was using a credit card.” A few days later, Haidara sent them the money. And near the end of January, just as the retreating Islamists were torching an empty Ahmed Baba Institute and Mayor Cissé was telling the world that the documents were lost forever, the final boxes arrived at their new homes. Haidara estimates that roughly 95 percent of the city’s 300,000 manuscripts made it safely to Bamako.

When I visited Timbuktu this March, a sign that had once read Welcome to Timbuktu, City of Sharia, was streaked with black paint—the only word remaining was Timbuktu. The city is back under government control, and Malian soldiers man checkpoints throughout the city and enforce a curfew. In the city’s central market, a handful of stores have reopened, and you can buy bread or a live chicken from a boy wearing a “New York Nicks” t-shirt.

Still, it will be quite some time before the city returns to normalcy. Green Malian army trucks, the only vehicles on the road, rumble through Timbuktu’s sandy, trash-strewn streets. Restaurants and hotels are closed, with the tourist industry almost entirely frozen. After a spate of recent attacks, the people who left during the occupation—including Haidara—have been reluctant to come back.

The manuscripts, too, won’t return to Timbuktu until the situation is more stable. When we met, Haidara refused to identify any of his couriers, worried about reprisals. He and Diakité are the only people in Mali who know where all the texts are currently hidden, but Haidara would only talk about those locations in generalities. “Some are in Bamako, some are in other regions,” he said. “But they are all in Mali, their home.”

Diakité says many of the documents are showing signs of mold, mildew, and other physical deterioration from their long journeys and from the change in temperature from the sweltering north to the cooler south. She and Haidara drained their personal savings accounts to pay for the evacuation. They recently formed a nonprofit called T160K—a nod to the 160,000 manuscripts that were initially smuggled out of Timbuktu—and are trying to raise money to move the manuscripts into individual, climate-controlled cases. Haidara has overseen the digitization of roughly 2,000 manuscripts, and thousands more have been digitized in other preservation projects, but many others remain completely vulnerable without that protection. “If you [lose] a manuscript, it’s gone forever,” he told me. “Each one is unique, with its own story. It can’t be replaced.”

Toward the end of our time together, Haidara asked if I’d ever seen any of the documents. I said no, just scraps, and he looked surprised and took out his cell phone. With the expression of a proud parent scrolling through baby photos, he showed me images from his former collections, now all boxed up and hidden. But his smile did not fade as he kept scrolling through photo after photo after photo.

Yochi Dreazen is a contributing editor at The Atlantic and a writer-in-residence at the Center for a New American Security. This story was reported with a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting