In June 1880, Fyodor Dostoevsky spoke before a monument to Alexander Pushkin, newly erected in Moscow, proclaiming Pushkin a “unique phenomenon of the Russian spirit.” To Dostoevsky at least, Pushkin’s monumental meaning was transparent. It was his national genius: “No single Russian writer, before or after him, ever associated himself so intimately and fraternally with his people as Pushkin.”

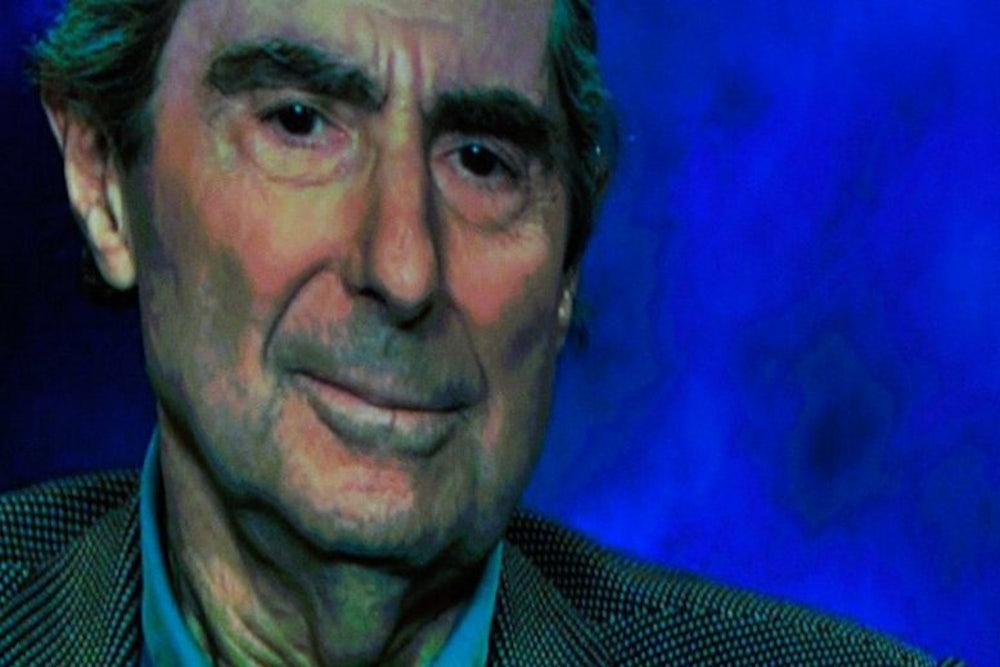

Unlike Russians, Americans rarely build statues to their writers. American writers are most consistently remembered as local heroes: Edgar Allan Poe obliquely commemorated in Baltimore’s football team or Ernest Hemingway honored as the patron saint of Key West. For all its statues, Washington, D.C. has very few that are literary. One of the limited ways to secure a spot in national memory is for a writer to be featured in American Masters, a PBS series that focuses on great artists. This accolade has just been awarded to Philip Roth, and “Philip Roth: Unmasked,” has all the attributes of a monument, though the question remains: A monument to what?1

It’s easier to answer in the negative. No monument can be built to Roth the Jewish-American writer, since there is no such writer. Roth does not write “in Jewish,” as he comically confesses in the documentary. The Jewish-American label was constructed by others and applied to him artificially, forcing him into a box with Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud when the literary genealogy is vastly more complicated.

But one need not label Roth a Jewish-American writer to explore a Jewish phase in American literary culture, a phase, from the 1950s to the ’70s, which happened to coincide with Roth’s rise to prominence. “Philip Roth: Unmasked” does justice to the Jewish milieu of Roth’s fiction, but it could have done more with the Jewish literary and intellectual milieu that guided, and at times infuriated, Roth in his younger years. Roth’s affinity for European literature and his avoidance of radical politics were determined in part by the (Jewish) New York intellectuals, his first literary critics. Roth made his claims for the bond between art and playfulness against the grain of New York intellectual seriousness.

Nor is the American Masters documentary a monument to Roth as the purveyor of literary scandal—either in terms of his alleged obscenity or extreme masculinity. Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), the film indicates, was scandalous not because of its sexual detail but because its narrative voice was so vivid, so funny, so human—and to American high school graduates, so familiar. Portnoy was one of us, and that was the scandal. By now, the scandal of Portnoy’s Complaint is obviously ancient history. “Philip Roth: Unmasked” gets the quaintness of it all—to a twenty-first century public—just right. As for an alleged masculinity of perspective in Roth’s writing, the documentary is agnostic. Either the maleness of Roth’s protagonists should simply be enjoyed or it is not a proper criterion of literary worth.

The American Masters documentary should have taken up the critique of Roth as too masculine a writer, because this critique still matters to Roth’s reputation. The accusation that Roth is a misogynist has currency in academia, and tellingly not a single academic is interviewed. More importantly, Roth’s unapologetic masculinity has long been a litmus test for younger writers. Writers like Nathan Englander and Gary Shteyngart celebrate Roth’s influence, while David Foster Wallace condemned Roth, Updike, and Mailer as the “Great Male Narcissists” of postwar American literature in a 1998 book review, a trio of writers to be rejected or, better yet, overcome with the power of gender-crossing empathy. At the very least, the existence of the anti-Rothians should have been acknowledged in this documentary.

If “Philip Roth: Unmasked” is not a monument to the Jewish-American writer or to Roth the provocateur, it may be a monument to a certain kind of literature. Monuments imply an era’s end, and the era coming to a close could be that of pre-digital literary culture—the era, for Roth, when the novel had a civic and social context. “The readership [for novels] is dying out,” Roth stated in a November 2012 New York Times interview about his retirement. “That’s a fact, and I’ve been saying it for fifteen years. I said the screen will kill the reader, and it has.” In a recent New Yorker essay, Adam Gopnik wrote that the author’s 80th birthday, may prove a “bon voyage party for the American writer’s occupation itself.” Is this the final message of Roth’s remarkable career? That he is the last of the Mohicans?

Troubled as “our confused new century,” in Gopnik’s phrase, may be, it will not witness the vanishing of literature. The American Masters documentary is a monument to something more specific than literature lost. It is a valedictory tribute to the writer-citizen whose literature encompasses national experience and, for that reason, is excitedly (or angrily) received by a national audience. Roth may have nothing else in common with Alexander Pushkin, but his association with the American people is intimate and fraternal. To reorient Dostoevsky’s melodramatic language, Roth could be characterized as a phenomenon of the American spirit; or, as Roth puts it in his documentary, he writes “in American.”

Writing in American, he stands in a long line of national writers, each of them a living presence in Roth’s own novels: Hermann Melville, William Faulkner (Roth’s Newark resembles Faulkner’s South), Saul Bellow. These writers depended on American novel readers, even if, in Melville’s case, it took a few generations for them to find their way to Moby-Dick. They also depended on the cherished idea of a national literary culture. American novel readers are dwindling, and the ideal of a national literary culture is fading away. It has been passed over by writers, critics, editors, publishers, and academics convinced that, to be good, literature must be global. Accordingly, most contemporary literature vacillates between the island of the self and an ocean of global detail. The national writer, a product of the nineteenth century, is a relic of the past. Yet it was Roth’s calling to be exactly this, to join nation and imagination and to serve his citizen-readers as a writer-citizen, the worthy object of as many monuments as the nation is willing to sponsor.

A Library of America series had already been devoted to Roth’s 31-volume oeuvre, honor after honor, prize after prize—with the exception of the Nobel Prize for literature, well known by now for not having been bestowed on Roth.