Conservatives have a new darling: Ben Carson. Or, as they prefer to call him, Doctor Ben Carson.

Carson is a neurosurgeon. And his biography is genuinely impressive. African-American, and the son of a single mom in Detroit, Carson won acceptance into Yale and then the University of Michigan medical school. He would go on to become director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, the youngest ever division director at that distinguished institution. He made news in 1987 when, leading a 70-person team, he was the first surgeon to successfully separate twins joined at the head.

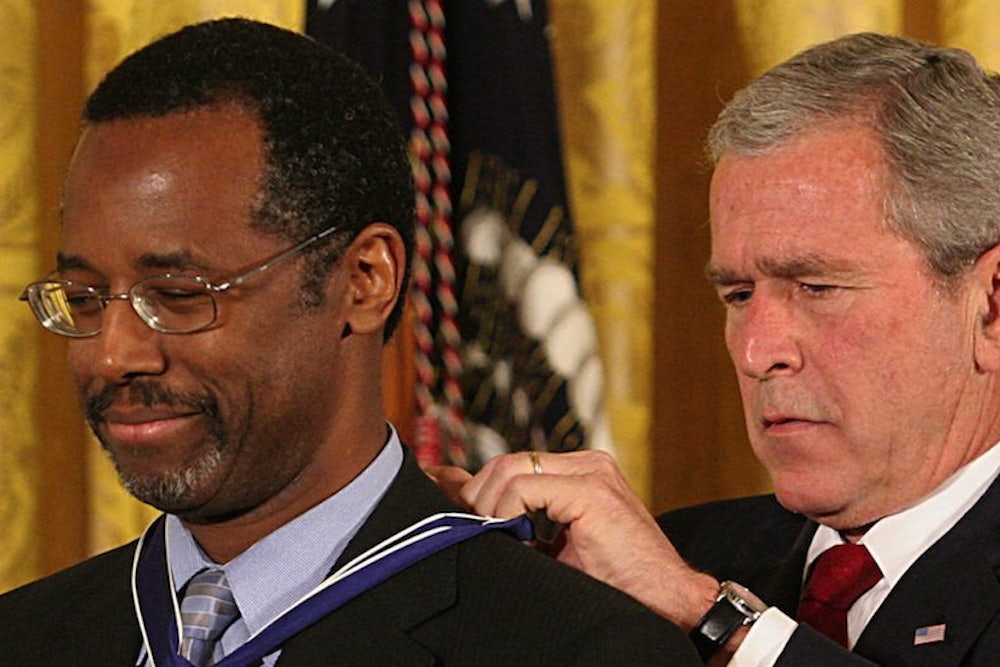

But political fame came only recently. In early February, during a speech at the National Prayer Breakfast, he bemoaned the national debt, attacked progressive taxation and took jabs at Obamacare—all with President Obama sitting just a few feet anyway. Then, at last weekend’s Conservative Political Action Committee (CPAC) meeting, Carson hinted at political aspirations. “Let’s just say if you magically put me in the White House...” he said. Rush Limbaugh could barely contain himself. “I think Dr. Benjamin Carson has probably got everybody in the Democrat Party scared to death,” he said.

Whether Carson is really the man of conservative fantasies remains to be seen. A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to debate him on WBUR’s “On Point” radio show. The subject was health care policy and I expected a sharp, all-out debate over first principles. Instead, we ended up agreeing a lot. I got the distinct impression his conservative positions on health reform didn’t go much deeper than talking points—that, for example, Obamacare emphasizes personal responsibility more than he realizes and that, once he worked through the details of policy, he’d come to realize that even a conservative version of reform couldn’t seriously improve access without substantial investments of money. Although I don’t imagine he’d ever endorse single-payer, he may be more open to the ideas of health reform than many of his would-be supporters.

Some of his views seem well-formed and deeply held: He staunchly opposes progressive taxation, he says, because it punishes the successful. But he has other ideas that might trouble his new conservative fans. In an interview with the Daily Caller, he revealed that he opposed not only the war in Iraq, but also the war in Afghanistan. He also hinted that he supports gay marriage.

Until we know more about what he actually thinks—and until Carson knows more about what he actually thinks—the phenomenon is more interesting than the man himself. Carson’s magical appeal to conservatives surely has something to do with his race; the more prominent African-Americans endorse conservative ideas, the harder it is to portray those ideas as harmful to African-Americans. But it also reflects Carson’s professional background, and the authority it gives him to speak about issues involving children, low-income Americans, and medicine. Here’s Limbaugh again:

It's gonna be really hard to demonize this guy -- really, really hard -- partially because of his race, but not just because he's African-American. It's because you can call this guy all kinds of demonic names; he just doesn't fit the bill. You can say he's all these horrible things; then you hear him, see him, and listen to him, and it doesn't click. He saves children. He saves children with his hands. He saves their little brains. He saves lit-tle children! He's a ped-i-a-tric neu-ro-sur-geon.

Yes, Carson has saved children. Just like Senator Tom Coburn, an obstetrician, has delivered babies and Senator Rand Paul, an ophthalmologist, has restored eyesight. And those experiences surely give them valuable, sometimes crucial insights into policy areas, particularly health care. But it’s a mistake to equate an M.D. with compassion—or to assume what a doctor always knows best when it comes to health care policy.

Although bound by tradition and professional oaths to act in the best interests of their patients, physicians frequently act out of self-interest—whether they are acting as individuals or as a group. To take one famous example, during the 1990s, an analysis published in the New England Journal of Medicine 1 showed that the American Medical Association’s political action committee was giving more money to the opponents of tobacco regulation than the supporters—even though tobacco was among its top public health priorities. The likely reason? The lawmakers who opposed tobacco regulation were also the ones who championed economic interests of doctors, such as supporting award caps on malpractice lawsuits.

The other thing to remember about physicians is that they have pretty diverse views. Historically, doctors have held prominent positions in both parties—for every Ben Carson, you had a Howard Dean. More often than not, views have broken down by the type of medicine physicians practiced. The specialists were more conservative, while the doctors who did primary care were more liberal.

If you look strictly at members of Congress today, that pattern isn’t quite as true as it used to be. Republican doctors in Congress now substantially outnumber Democratic doctors. And while most of Republican physicians are still specialists—Congressman Tom Price is an orthopedic surgeon, for example—the House GOP delegation now includes a handful of family doctors. But the predisposition of the groups remains the same. Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Physicians (which represents internal medicine doctors), and the American Psychiatric Association all endorsed Obamacare enthusiastically—and have continued to champion it, in some cases filing amicus briefs defending the law before the Supreme Court last year. The surgical and specialty groups mostly said stayed quiet, though none of them actually opposed it, as far as I know.2

Financial self-interest has something to do with this. Obamacare is changing reimbursement in ways that should reduce the financial incentives for additional tests and procedures, because the best available evidence suggests overtreatment is a major problem in American medicine—driving up costs and, by the way, sometimes doing more harm than good.3 You can imagine why surgeons, who make a lot of money by performing a lot of procedures, might not like the sound of that. But the differences in worldviews also reflect the divergent styles of medicine that physicians practice. I wrote about this ten years ago, when Senator Bill Frist, a Republican and highly respected heart transplant surgeon, became majority leader:

Not only do surgeons make a lot more money than primary care doctors, fostering different worldviews on issues like taxes and government reimbursement levels; they also practice medicine in strikingly different ways. Surgical specialists, as the term suggests, develop deep but narrow expertise on one part of the body or even one particular procedure that a patient may need just once in a lifetime. Primary care physicians, by contrast, must consider patients as large, interrelated systems whose health they must maintain over the course of years. … surgeons worry a great deal about anything that might stunt technological innovation, a problem they see as related to government regulation and cost controls. Primary care physicians, on the other hand, spend a lot of time watching how outside factors--environment, poverty, lack of insurance--affect their patients' well-being, and they frequently see government as a means for correcting these problems.

It’s as true today as it was in 2003. Conservatives love Carson because he allows them to put a more compassionate face on the same old, unpopular ideas. His compassion may be as real as his expertise; I have no reason to doubt either. But the test of policy is its real-world effect—whether it will make it harder for people to get medical care, to make rent, or to buy food. And nothing that Carson has said comes remotely close to suggest the conservative policies he’s advocated are less harsh than they seem.

The authors of the original study were Joshua Sharfstein, then a medical student, and his father Stephen Sharfstein, a psychiatrist and head of Sheppard Pratt Hospital System in Baltimore. The younger Sharfstein, who happens to be a friend, went on to become a pediatrician and is now commissioner of health for the state of Maryland.

Harold Pollack and Vivek Murphy have written about the medical profession’s attitudes about health care reform about a year ago, in response to some misleading polling information.

The ur-text on this subject is Shannon Brownlee’s Overtreated. Among other things, the book draws on studies from Dartmouth researchers showing wide disparities of treatment intensity across the country—with little apparent correlation to quality.