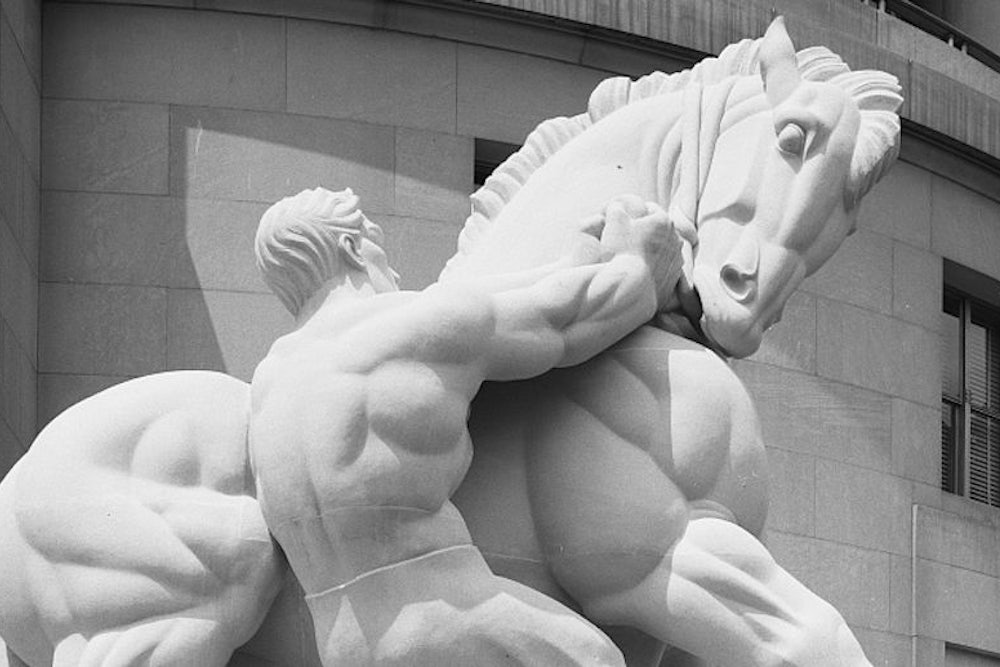

“There is a statue outside the Department of Labor,” David Brooks writes today in his New York Times column, "of a powerful, rambunctious horse being reined in by an extremely muscular man. This used to be a metaphor for liberalism. The horse was capitalism. The man was government, which was needed sometimes to restrain capitalism’s excesses."

This statue (“Man Controlling Trade”), which is located 1.7 miles from the Times’s Washington bureau, does not stand outside the Labor department. It stands outside the Federal Trade Commission. This error sets the tone for a column that argues we can’t raise taxes on high incomes without wrecking the economy. That’s false, too.

Brooks is appalled that the Congressional Progressive Caucus wants to raise the top tax rate all the way up to 49 percent. That’s one percentage point below the top rate in 1984, the year Ronald Reagan campaigned for re-election on the theme, “It’s morning again in America.” The 50 percent top marginal rate of 1984 kicked in at the equivalent, in today’s dollars, of $241,000. The Bolsheviks at the Congressional Progressive Caucus propose having it kick in at $1 billion. They would also like to tax capital gains as regular income, which Reagan did in the 1986 tax reform bill.

If we set taxes at these “astronomical levels,” Brooks says, “you really do begin to change behavior and wind up with a very different country.” But what we got starting in 1983 was a reviving economy that continued to expand, even after a stock market crash, until 1990.

That’s not the kind of “different” Brooks has in mind. In the 1950s, he writes, when taxes were low in Europe and high in the U.S., Europeans worked more hours per capita than Americans. But who cares how many hours people worked? In both places Gross Domestic Product boomed. What matters is productivity, which doesn’t measure how long you stay at work; it measures output per hour. During the 1981-2 recession, somebody (I forget who) took out a newspaper ad showing a crowded Grand Central Station. “If this many people are in Grand Central Station at 10:30 p.m.,” the ad said, “how come U.S. productivity is down?” Good question, I remember thinking. Throughout the 1950s productivity growth was brisk in both Europe and the U.S. (It was also brisk in the 1980s in the U.S. after the recession ended.)

Throughout the 1950s the top marginal income-tax rate in the U.S. was above 90 percent. “But the total tax burden was lower,” Brooks writes, “since so few people paid the top rate and there were so many ways to avoid it.” This is a red herring. By “tax burden” Brooks appears to mean the share of the nation’s income taxes paid by the wealthy, which is actually about the same today as it was in the 1950s. That reflects changes in income distribution (you may have heard incomes have become steadily more unequal since 1979) and the tax burden on lower incomes (reduced, largely at the instigation of conservatives).

The total federal tax burden was higher in the late 1950s if by “tax burden” you mean taxes paid not by the rich but by everybody. The average federal income-tax rate paid by a family of four was higher. That’s because in those days Americans actually paid for the government services they consumed. Today we borrow to pay for them. If we could raise the nation’s collective tax burden, restore the budget to solvency, and end up with the economy of the 1950s, that would be a pretty good deal.

What Brooks is trying to say, I think, is that in the 1950s the rich didn’t really pay a higher “effective tax” (i.e., a greater percentage of their income in taxes) than they do today. This is an untruth oft-repeated by conservatives in the hopes that they can convince you that raising the top marginal rate is at best futile and at worst economically destructive. But it is not futile; the rich really did end up paying more in taxes back in the 1950s.

I’m not saying that a top marginal rate of above 90 percent is optimal with respect to the larger economy. (The economists Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez say 70 percent would be better.) But it did squeeze more money out of wealthy people. But what about those loopholes? Actually, as a share of adjusted gross income, total deductions were lower in the 1950s than they are today, not higher. That’s why so many people are demanding tax reform today. But the lesson of the 1950s is that you can eliminate tax loopholes and raise rates well above their level today, and still end up with a healthier economy than the one we’ve got today.

That horse Brooks misidentifies is a pretty powerful beast. Yanking a bit more forcefully on its reins won’t weaken it, I promise. It may even strengthen it.