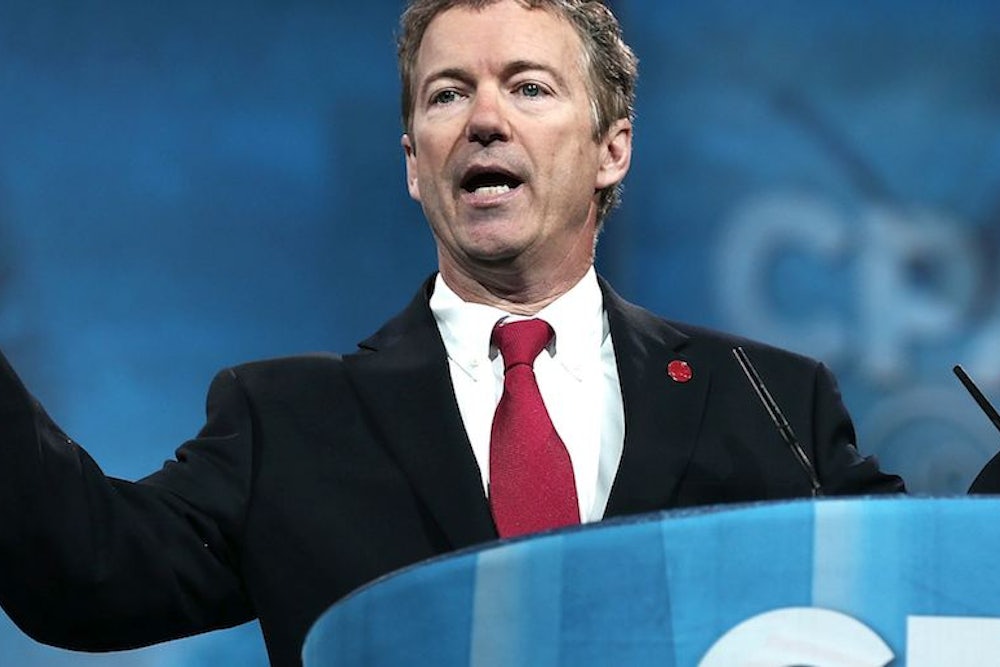

Conservative thinkers have been brainstorming ideas to revive the GOP, but few Republican politicians have been as bold. The most prominent 2016 contenders, like Jeb Bush and Senator Marco Rubio, have chosen an uninspiring two-step approach: cave on immigration; repackage the party's message. Perhaps the only presidential hopeful grappling with the scale of the party’s problems is Rand Paul, the winner of last week’s CPAC straw poll. He proposes to use libertarianism, once consigned to the fringes, to broaden the party’s appeal to a demographic that's increasingly Democratic: young voters. And he proposes himself, of course, to lead that movement. Would such a plan work?

Despite all the talk about courting Latinos, the Republican Party has a bigger, generational challenge. Romney actually won voters over age 30 by 2 points.1 But they were overwhelmed by Obama’s decisive 24-point victory among 18-29 year old voters. Race partly explains the GOP’s youth problem, since just 58 percent of 18- to 29-year-old voters were white in 2012, compared to 76 percent of voters over age 30. But the GOP underperforms among young voters even after controlling for race: Romney fared a net 15 points worse among young whites than those over age 30. Republicans will probably underperform among millennial voters in perpetuity for historical reasons: 18-29 year old voters came of age during the prosperous Clinton and disastrous Bush years. But the GOP certainly isn't helping itself by taking conservative positions on critical cultural issues, like gay marriage and abortion, which are opposite those of a majority of millennial voters.

Rand Paul's Republican Party would probably still struggle among young voters, but at least he offers targeted proposals to narrow the gap. For instance, he supports states' rights to legalize marijuana. Recent polls show that nearly 70 percent of young voters support legalizing marijuana, just as nearly 70 percent of young voters in Washington and Colorado supported initiatives to legalize marijuana last November. Paul also advocates a less aggressive, less costly foreign policy. Millennial voters, having come of age during the Iraq War and without memory of the Cold War, tend to agree: Just 44 percent of 18-29 year olds think the best way to ensure peace is through military strength, compared to 63 percent of voters over age 50. The age gap on foreign policy is even more evident when considering specific policies. Only 28 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds want to “get tough” with China, while twice as many—55 percent—of voters over age 30 support getting tougher with China. Similarly, while 30 percent of voters over age 30 would prioritize avoiding a conflict with Iran over taking a “firm stand” against the country, 49 percent of young voters would prioritize avoiding war.

When combined with a pathway to citizenship for undocumented workers, which Paul also supports, these measures push up against the limits of what the Republican primary electorate could potentially support. Marijuana is a new issue, and the GOP could conceivably go either way: On the one hand, CBS News found that 65 percent of Republicans support allowing state governments to determine the legality of marijuana, compared to just 29 percent who believed the federal government should decide; on the other hand, Quinnipiac and CBS News polls found that 66 percent of Republicans think marijuana should be illegal.

On foreign policy, Paul is more clearly at odds with a majority of Republican partisans: 73 percent of Republicans believe the best way to ensure peace is through military strength; 74 percent of Republicans would take military action to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon, including 84 percent of self-identified Tea Party Republicans. Nonetheless, it’s conceivable that Paul could advocate for a more moderate foreign policy. Defense issues are on the backburner, and reduced military spending is consistent with reducing the debt, the stated top objective of Republican voters. And Rand has been far savvier than Ron: He’s trying to ameliorate the concerns of pro-Israel forces, and his attacks on the Obama administration’s drone policies draw on paranoid fears of unmanned planes gunning down Americans.

Rand Paul's savvy has paid off in decent poll numbers. PPP found Paul with a higher favorability rating among Republicans than every 2016 contender but Paul Ryan. Paul’s likely to inherit his father’s infrastructure and supporters—which was worth 21 percent in Iowa and 23 percent in New Hampshire. If Paul makes modest gains over his father’s performance and a strong Republican field divides the traditional conservative vote, Paul could conceivably win Iowa and New Hampshire, giving him a real shot at the nomination. Of course, even in that best-case scenario, Paul could struggle as the race headed south and orthodox conservatives united around a more traditional candidate, whether it’s Rubio, Bush, Ryan, Walker, or someone else.

But even if Republicans could agree to moderate on foreign policy and marijuana, Paul’s probably not the right messenger for his own proposals. He wants to abolish the Federal Reserve and opposes elements of the Civil Rights Act—neither position commands the support of a majority of voters, let alone Republicans. Despite the big political risks, Paul’s libertarianism doesn’t offer the GOP many benefits in return. While some might interpret his strength among younger voters as a sign that the GOP could benefit from a more libertarian tone, 59 percent of young voters believe that the government “should do more.” Young voters are libertarian on cultural issues, but Paul is pro-life and against gay marriage. Even if young voters were libertarian on economic issues, the GOP’s small-government message attracts many of the same voters persuaded by economic libertarianism, without the cost of questionable ideas like ending the Fed. If Paul’s proposals for restraint abroad and marijuana at home would help Republicans, the party would be best served by attaching those proposals to a more traditional conservative, not Rand Paul.

That shouldn’t be surprising if you might think them of as the voters of the 2000 election, who were ages 30 or higher in 2012. The slight GOP-lean of the 2000 electorate is even less surprising if you remember that the very oldest voters from the 2000 election were quite Democratic, since they came of age during the Roosevelt administration.