“I have no faith in anything,” says Maurice Sendak in his final interview. “I never have, much.”

Sendak, author of children’s books both widely beloved (Where the Wild Things Are, In The Night Kitchen) and staunchly defended (Outside Over There, We Are All In The Dumps With Jack and Guy) died last May at the age of 83. But the just-published issue of The Comics Journal (#302), a now-annual compendium of writing in and about comics, features an interview with Sendak that runs more than 100 pages. Conducted six months before Sendak's death by Comics Journal publisher Gary Groth, the interview takes place over the course of a leisurely stroll through the acreage of the author’s Connecticut home on a pleasant October afternoon (as well as a follow-up phone interview weeks later). Groth’s visit finds Sendak in a voluble mood.

A voluble, reflective, seriously crabby mood. “I seem to always be talking about death,” he says, accurately. “I hate that it’s almost over. I hate it.”

Excerpts of this interview can be found online, in two parts, here and here. But excerpts don’t do justice to the breadth of this lively, comprehensive and fascinating discussion. Do yourself a favor and pick up the issue itself, a phonebook-thick (600+ pages!) copiously illustrated, gorgeously designed tome of a thing, a steal at 30 bucks.

You need to read the whole thing because in discrete doses, Sendak’s mordant jokes can come off as merely shrill, as when he discusses his ardently held fantasy to arrange a visit to the White House, don a suicide bomb and vaporize George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, their wives, and himself. (“And then we’ll blow ourselves up, and I’d be a hero ... ‘To hell with the kiddie books: He killed Bush!’”) Or his contention that, after receiving a bad review from Salman Rushdie, he reached out to Iran’s Ayatollah on direct-dial. (“…I called him and I said, ‘Kill that man.’ And he said, ‘OK, Maurice, anything you say.’”) Or his pitched loathing of Christmas (“gross, vulgar, shitty”), the publishing industry (“I want to kill everybody”) and his irrational hatred of celebrities like Alec Baldwin (“That fat fuck”), Steven Spielberg (“A pile of shit”) and Meryl Streep (“Gornischt, genug, genug!”)

You get the idea. And that’s not even mentioning the fact that he named his dog after Herman Goering. (He sticks with this assertion, though given Sendak’s oft-expressed affection for Melville, it can’t help but push the needle of your irony detector into the red.)

The interview takes place five years after the death of Eugene Glynn, Sendak’s partner of 50 years, and not long after the death of a dear friend and his wife, in swift succession. At one point, he shows Groth a field where, just scant weeks before, a beloved copse of trees once stood, now ravaged by Hurricane Irene. The man’s got cause to kvetch, in other words, and does so with relish, and with liberal doses of Yiddish, in a dependably old-man-yells-at-cloud manner. He laments the sorry state of movies (the few actors spared his considerable wrath include Simone Signoret, Claudette Colbert and Rudy Vallee) opera (once uncanny and moving, now “sexy and cheap”) and life in New York City (“the silliest place on earth.”)

I hear you wondering: Why on earth would I want to read 100 pages of caustic carping?

Because Sendak is funny. Deeply, passionately so. Read in full, Sendak’s zingers lose their venom and evince a sincere and surprising warmth. He comes off as bitter, but not embittered—a fine distinction, perhaps, but a real one.

Groth nails it, in his introduction to the interview, when he describes Sendak as “quite cheerfully and gregariously grumpy” and notes his “fatalism touched with a blithe spiritedness.”

Exactly. The interview reads as nothing less than a testament to the vivifying, defiant, self-rescuing power of pitch-black humor employed as a bulwark against despair.

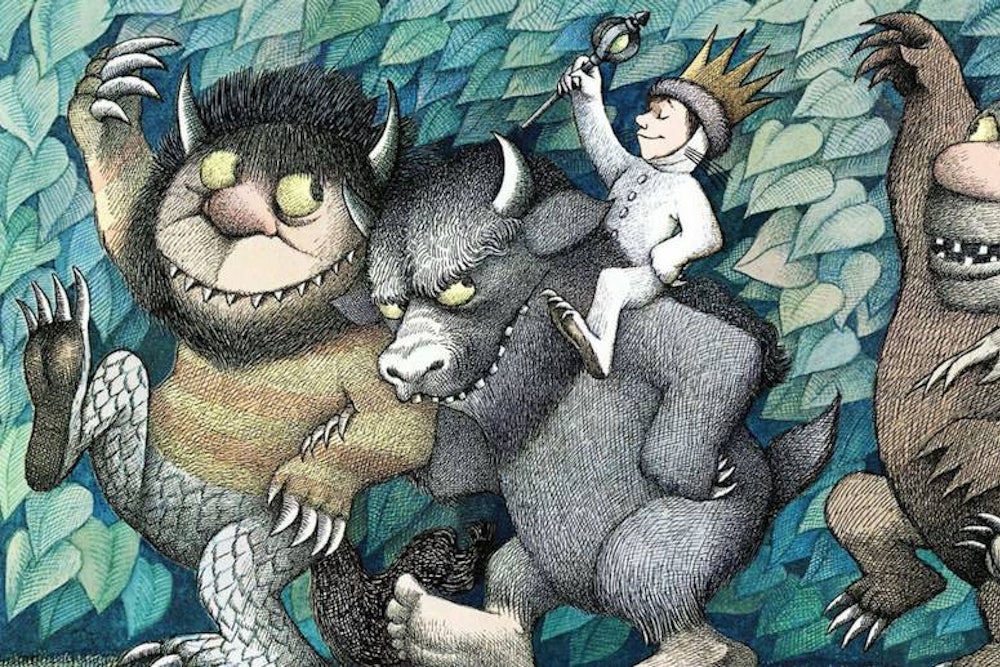

His oft-repeated refrain (“That’s just the way it is!”) carries not the faintest trace of sorrow or self-pity. It is instead a rallying cry, an acidic yawp of pure rationalism, a jut-jawed justification for his mode of art, and his mode of life: The curmudgeon’s manifesto. It’s a mantra he employs often when describing his irritation at parents and teachers who express concern about the traumatic themes in his work. In Sendak’s view, he’s simply being honest with kids. Children see everything, he insists, even (especially) the darkest truths. He tells Groth of a time in his very early childhood when he glimpsed a newspaper photo of the corpse of the Lindbergh baby. That horrifying image wasn’t one that he could discuss with his parents, and it haunted him throughout his life (and inspired Outside Over There). Kids grapple with this stuff all the time, he says, they just don’t tell us about it. Books like Where The Wild Things Are, which deal matter-of-factly with primal fears of abandonment, help kids localize and exorcise their anxieties. Parents who pretend that bad things never happen are keeping the truth from their kids, he says. “And when you take away the truth, you take everything from them.”

Reading Sendak explain this philosophy of truth made sense to me. In fact, it was a revelation. Suddenly I remembered why I, as a child, had always found Sendak’s work tremendously upsetting, Where The Wild Things Are in particular. The Wild Things were scary, sure, but that wasn’t it. No, my problem was with the book’s hero, Max. To put it simply: Max is a dick.

A spoiled, belligerent, self-impressed dick who reminded me of the schoolyard bullies I so feared and loathed. It angered me that Max’s essential dickishness was the very thing that wins him the title of King of the Beasts. I also wasn’t too crazy about the Wild Rumpus itself, the sight of which always gave me a stomachache. It was clearly only a matter of time before someone got hurt, the way they were carrying on; they should really dial it down a notch for safety’s sake. (I was a follower of rules who also couldn’t read The Cat in The Hat without wondering angrily why nobody was listening to the very sensible goldfish, who was just looking out for everyone.)

But it was Where the Wild Things Are’s particularly galling coda that really set me off, when Max gets home and discovers that the dinner he was sent to bed without (on account of his by now amply demonstrated complete-dick status) is now just waiting there for him, still warm.

This, of course, rocked my 5-year-old worldview, inasmuch as it represented a gross violation of the most basic tenets of fairness and propriety. Do actions not have consequences, I wondered? Sendak, I now realize, had provided my question with its answer, even though it would take me years to learn it for myself: “That’s just the way it is!”

There is also a moment midway through the interview when the conversation turns to Sendak’s closest childhood friend, Pearl Karchawer, who died at the age of 12. Sendak finds himself growing emotional at her memory, clearly re-experiencing the pain he felt as a child, more than 70 years before. What he says next is surprising, coming from a man so armored and unsentimental, but it’s this very dissonance that lends his words their spare, simple, quietly revelatory power.

SENDAK: But why does it matter anymore? I can’t answer that.

GROTH: But somehow don’t you think it does matter? Even if you don’t know how or why, I mean, doesn’t it matter?

SENDAK: It does matter.

GROTH: It matters because she lived.

SENDAK: And I keep her inside of me. It’s like I’m a receptacle, a repository for all the people I love. All I can do with them is keep them.

Amid Sendak’s reflexive irony and dark, cutting humor, this brief, unguarded exchange (which, had it come from someone, anyone else, might seem saccharine) feels like something a man facing down the end of his life wishes to leave behind him—a gift. Something small and sad and resolutely true: “All I can do is keep them.” That’s just the way it is.

Glen Weldon is a freelance writer and panelist on NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour. His book, Superman: The Unauthorized Biography, will be published in April.