Touré has been frustrating me lately.

For most of the 20 years that he has been writing about pop culture, in publications like Rolling Stone, Time and Vibe, I’ve found his work to be unremarkable. Nothing great, nothing terrible. Except maybe for the time in 1997, after the Notorious B.I.G. was killed, when he declared in the Village Voice that he would never write about hip-hop again—and, within a year, was back writing about hip-hop; that was pretty terrible. But mostly, it’s been just, eh. And watching him in his current incarnation as co-host of MSNBC’s daytime talk show "The Cycle" has done little to change that.

So it came as a nice surprise when I picked up his recent book, Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness?, a collection of essays and interviews about, as the subtitle explained, What It Means to Be Black Now, and liked it a lot. Touré tends toward overwriting. Superfluous explication, heavy-handed metaphor, repetition—tics that can make for tedious reading. But on a subject as complicated and difficult as race in America, the style served to flesh out amorphous ideas and give them clarity and depth. Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness? is a good book that says important things.

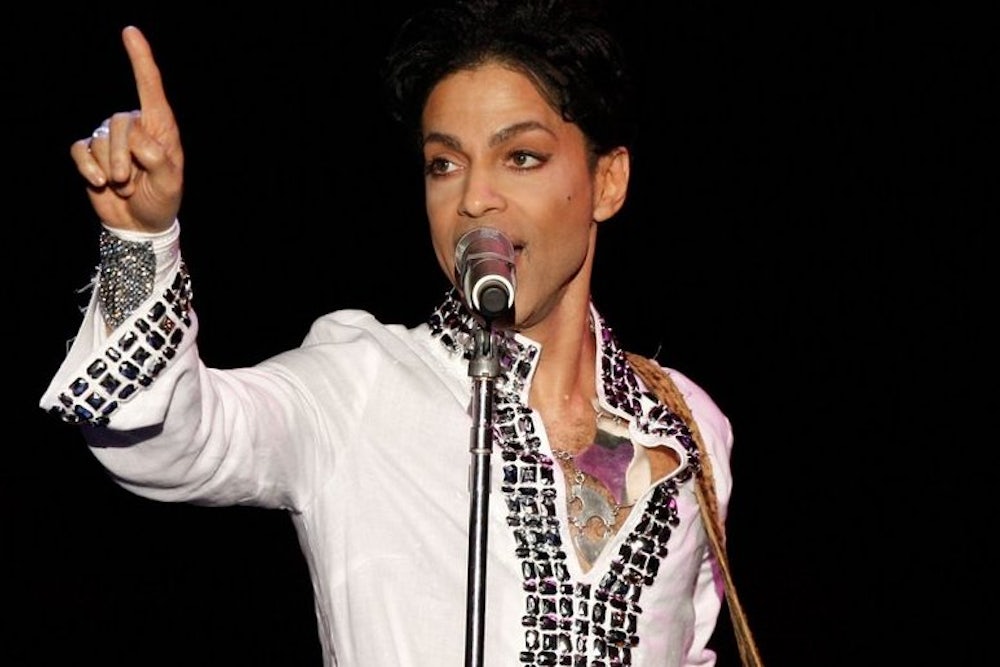

That experience had me looking forward to his new book—a biographical examination, richly researched, that presents a grand theory about one of my favorite musical artists: Prince. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out so well. The project would better serve as an article in an academic journal or a short lecture. (The book is based on a talk Touré gave at Harvard’s Alain Leroy Locke Lecture Series.) Reading 150 pages of it was a drag, like sitting through a seminar by the longest-winded professor at your college. You find yourself saying “all right already!” a lot. Pretty much the opposite of listening to Prince’s music.

The arguments Touré makes in I Would Die 4 U vacillate between two poles: so obvious that they are unnecessary for anyone with even a basic familiarity with Prince’s music and so general that they are meaningless for anyone at all. His thesis is that Prince, a Baby Boomer born in 1958 and defined by the divorce of his parents, identified the cultural needs of Generation X—an entire generation defined by divorce—and calculatedly imbued his music with pornographic sexuality in order to entrance an audience to whom he could deliver his true message: evangelical Christianity. Touré delivers this with armfuls of armchair analysis and an off-puttingly strident adherence to psychographics—or, as he defines it, “classifying people by psychological criteria like attitudes, fears, values, aspirations, and the cultural touchstones that mean the most to them.” Vast conjecture presented with unearned certitude.

“For gen X,” Touré writes, “the seminal event that binds the generation and shapes and defines who we are and what we will become is divorce.” (More colloquially, Gen X is defined as those born between 1965 and 1982; Touré falls into this category, as do I.) He cites elevated divorce statistics of the 1970s and ’80s and continues, “For many young people, divorce is akin to an apocalypse … [It] can create emotional ruptures that will never heal, thus fueling much of the cynicism, skepticism, disillusionment, nihilism, and distrust of traditional values and institutions that mark gen X.”

The thing is, many of us skeptical “gen Xers” are skeptical of the idea of “gen X” itself. I find it distastefully reductive—I don’t much like the idea of being reduced to a stereotype.1 But Touré has strong words for us: We Gen Xers can’t escape the impact of “being the small, apathetic generation that followed a large, optimistic generation thatattempted to revolutionize America. Denying that is futile.”

Even if we grant Touré the reality of Generation X and its stereotypical characteristics (which: fine, sure, okay), the claims that follow don’t hold up. “Gen X Americans have lived within a negative political climate our whole lives,” he writes, “causing widespread alienation, disaffection, and apathy.” Really? I’m not sure I would define the political climate of the 1980s that way. (Negative compared to what?) And even if I did, I’m not sure that we can pin it as the cause of those effects. And regardless of the validity of Touré’s blanket statements, I’ll be happier if I never again have to read the sentence, “Denying that is futile.” (Pistols at dawn, good sir!)

It gets worse. The notion that Prince “read” the alienation, disaffection, and apathy of a generation of Americans and then used his music to, basically, trick them (us) into receiving a veiled religious message is, frankly, insulting—carrying with it the implication that we fans were too dumb to realize what it was we were liking about our favorite music. Never mind the fact the religious themes in Prince’s music are hardly as veiled as Touré seems to think. As Touré mentions many times, his most famous album, Purple Rain, begins with the words, “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today…”

Yet endless pages are spent dissecting readily apparent observations. The song “I Would Die 4 U,” Touré informs us, is “filled with allusions to Jesusness.” He notes the lyrics, “If you’re evil, I’ll forgive you by and by,” and takes the time to remind us that, “Jesus was forgiving of evil,” before noting that Prince also sings, in the same song, “I’m your messiah.” “Is Prince singing in the voice of Jesus,” Touré asks us, “or does he want us to think he is the second coming?” I guess no one can know for sure.

Prince’s lyrics, like many lyrics, are often cryptic and multilevel. A variety of people will find a variety of meanings in them. Detective-style parsing can be fun, especially huddled around the dorm-room bong at 3 o’clock in the morning. But asserting conclusions as evidence in support of his theory is unfair—and in this case, it too often reads like a freshman English paper. One long and particularly painful riff suggests that the line “I got a lion in my pocket and baby, he’s ready to roar,” from the title track to the 1999 album, is a biblical reference. “Revelation speaks of the Lion of Judah, a symbol for Christ,” Touré writes. “Perhaps the lion is a reference to Jesus as in Prince is saying Christ is with him.”

Perhaps? But perhaps not. And I will do my best not to think about any of this the next time I listen to Prince.

Another one of my favorite musical artists, Stephen Malkmus of the rock band Pavement, who found himself saddled with poster-child status for Generation X soon after Douglas Copeland coined the term with his so-named 1991 novel, sings a song called “Fight This Generation.” The title is repeated 15 times at the end of the song, a refrain that’s often taken as a rejection of the concept.